Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 25 No. 2 P. 10

Dietitians have heard the dire statistics before. The prevalence of obesity in the United States has increased dramatically over the past few decades from 30.5% in 1999–2000 to 41.9% from 2019–2020. If that wasn’t concerning enough, during the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, weight gain among Americans accelerated, worsening the preexisting epidemic of adult obesity. Studies reported an average weight gain of anywhere from 1.5 to 4.4 lbs during that time. Weight gain was greater among those who already had developed obesity.1,2

While diet and lifestyle changes still are considered the foundation for weight management, research has found that they have limited long-term effectiveness for most individuals.3 To aid weight loss in people who have had inadequate response to lifestyle interventions alone and reduce the risk of obesity-related complications, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) developed and published guidelines for several prescription medications and rated the medications for the strength of evidence supporting them.4

According to Colleen Rauchut Tewksbury, PhD, MPH, RD, CSOWM, LDN, a spokesperson for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and a senior research investigator in the Penn Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Program at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia, “Current estimates suggest that up to two out of three adults could be a candidate for an antiobesity medication.”

The AGA’s review of studies using antiobesity medications found that reported weight loss was substantially higher in the groups receiving medications, ranging from 3% to 10.8% of total body weight. But the AGA reports that there’s limited use of these medications in routine clinical care. In fact, only a small number of health care providers are responsible for more than 90% of the prescriptions for antiobesity medications, partly due to lack of familiarity, limited access, and poor insurance coverage.5

The AGA guidelines are the most recent and detailed that have been issued for the use of antiobesity medications. The organization’s overarching recommendation is for adults with obesity or overweight with weight-related complications—who have an inadequate response to lifestyle modifications—to add long-term pharmacological therapy to lifestyle interventions. The recommendations don’t address the use of pharmacological treatment for childhood obesity. The guidelines further say that antiobesity medications generally need to be used chronically, and their selection should be based on the clinical profiles and needs of patients, including, but not limited to, comorbidities, patients’ preferences, costs, and access to the therapy.

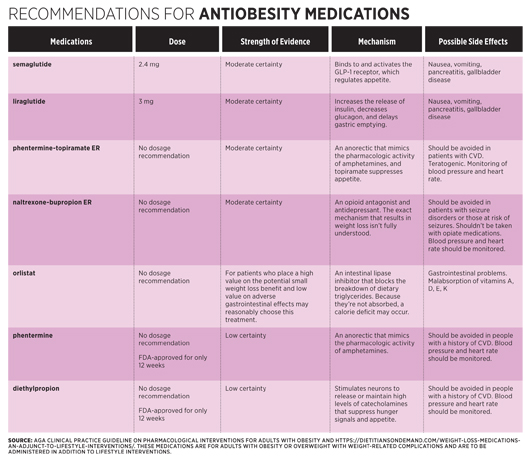

The specific medications for which the organization provided recommendations included semaglutide (Ozempic), liraglutide (Victoza), phenterminetopiramate extended-release (Qsymia), naltrexonebupropion ER (Contrave), orlistat (Xenical), phentermine (Lomaira), and diethylpropion (Tepanil).4 These medications have been FDA approved to treat adults with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or greater with a weight-related condition, or with a BMI of at least 30 kg/m2, who have had an inadequate response to lifestyle interventions. Antiobesity medications also are sometimes used either before or after bariatric surgery, but according to Rauchut Tewksbury, “We’re still learning more about their use before and after bariatric surgery, but it isn’t unusual for people to use these medications both before and after surgery.”

It’s worth noting that these medications should be used only as adjuncts to lifestyle changes. The dietitian’s role is still essential. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials compared people receiving counseling from a dietitian with those receiving usual care without a dietitian’s consult and found that those receiving counseling sessions with a dietitian lost more weight than those who didn’t see a dietitian.6

Side Effects

Each of these medications has the potential for causing side effects and interactions with other medications. Depending on the antiobesity drug, side effects can include nausea, constipation, headache, vomiting, diarrhea, insomnia, elevated blood pressure, and dry mouth. Preexisting conditions sometimes can rule out the use of a specific antiobesity drug. “Each medication has specific conditions where it would not be an option,” Rauchut Tewksbury says. “But for the most part, these medications have fairly limited contraindications or medical interactions to be concerned with and are best handled on a one-to-one basis.” Working with the patient’s physician and obtaining the patient’s medical history is critical for monitoring and managing side effects and potential drug interactions.

— Densie Webb, PhD, RD, is a freelance writer, editor, and industry consultant based in Austin, Texas.

References

1. Lin AL, Vittinghoff E, Olgin JE, Pletcher MJ, Marcus GM. Body weight changes during pandemic-related shelter-in-place in a longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e212536.

2. Seal A, Schaffner A, Phelan S, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and stay-at-home mandates promote weight gain in US adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2022;30(1):240-248.

3. Dombrowski SU, Knittle K, Avenell A, Araujo-Soares V, Sniehotta FF. Long term maintenance of weight loss with non-surgical interventions in obese adults: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2014;348:g2646.

4. Grunvald E, Shah R, Hernaez R, et al. AGA clinical practice guideline on pharmacological interventions for adults with obesity. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(5):1198-1228.

5. Saxon D, Iwamoto S, Mettenbrink C, et al. Antiobesity medication use in 2.2 million adults across eight large health care organizations: 2009-2015. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(12):1975-1981.6. Williams L, Barnes K, Ball L, Ross L, Sladdin I, Mitchell LJ. How effective are dietitians in weight management? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Healthcare (Basel). 2019;7(1):20.