Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 28 No. 1 P. 20

Over 5 million patients are admitted to an ICU in the United States every year.1 While many patients only spend a day or two in the ICU, those that are critically ill stay much longer. Patients who survive the initial illness which precipitated their ICU stay sometimes do not fully recover and continue to require intensive medical care and rehabilitation. This state is often referred to as chronic critical illness (CCI), persistent critical illness, or postintensive care syndrome.

There’s a lack of consensus on a specific definition of CCI; however, widely recognized symptoms include persistent weakness or frailty, mood disorders, and impaired cognitive function. In a recent meta-analysis, authors reported the use of a wide variety of definitions for CCI; the most common criteria were ICU length of stay (LOS), duration of mechanical ventilation, and persistent organ dysfunction. The most common ICU LOS used to define the condition was ≥ 10 to 14 days. Considering the lack of consensus on a definition, the prevalence of CCI is difficult to ascertain; however, authors estimated that 16% to 19% of critically ill patients worldwide develop CCI.2

CCI results in poor clinical outcomes—many patients never return to their pre-ICU level of function and independence, resulting in reduced quality of life. Patients with CCI have an average ICU LOS of 27 days, compared with 2.1 days for all ICU patients. Risk of death is high; reported in-hospital mortality is 26% to 29% and one-year mortality is 32% to 58%. Nearly two-thirds of patients with CCI cannot be discharged directly home—64% are discharged to another hospital, rehabilitation facility, skilled nursing facility, or hospice.2

Care for patients with CCI is affected by the setting to which they are discharged. Patients discharged home may receive care at an outpatient postintensive care clinic, a key feature of which is treatment provided by a team of interdisciplinary professionals, including an RD. This treatment model was proposed by the Society of Critical Care Medicine in 2010, and the first such clinic was started in the United States in 2011. While adoption in the United States has been limited, this treatment model has been used in other countries since the mid-1990s, most notably in the United Kingdom.3 Patients that still require complex medical care, such as continued mechanical ventilation, will require treatment at a long-term acute care hospital. Skilled nursing facilities are utilized for patients who need less medical care but are too weak to endure the required amount of therapy provided in a rehabilitation facility.

Regardless of the setting, the role of the RD in recovery from CCI is crucial. Patients with CCI have unique nutritional needs and challenges as they transition from the acute to chronic phase of critical illness, and graduate to lower levels of care. Knowledge of the physiological changes and nutritional treatment challenges associated with acute critical illness (ACI) is necessary to accurately assess nutritional status and develop effective nutrition care plans for patients with CCI.

Acute Critical Illness

The hallmark of ACI is severe inflammation. Inflammation is the body’s protective response to an illness or injury, and functions to remove damaged tissues, fight infection, and initiate healing. Inflammation is usually of mild severity, self-limiting, and a necessary component of recovery. However, it can become severe in conditions such as a major traumatic injury, rapid onset of a severe illness or infection, or exacerbation of a chronic medical condition, leading to ACI. Severe inflammation is characterized by a catabolic state; production of proinflammatory cytokines increases and negative acute phase proteins such as albumin decreases. This state of severe inflammation can result in major organ dysfunction, affecting the respiratory, renal, neurological, hematologic, and hepatic systems, necessitating the use of intensive medical support such as mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, and vasopressor medications. The level of medical support and degree of sedation needed to treat ACI often dictates the provision of enteral nutrition (EN) to meet nutritional needs.

Critical care nutrition guidelines provide guidance on energy and protein needs, initiation and advancement of nutrition support regimens, provision of micronutrients, and recommendations related to specific disease states. Nutritional requirements are altered in acute illness; however, there’s still considerable debate on the ideal intake of both energy and protein to optimize outcomes. In the case of energy intake, more isn’t always better—limiting the amount of energy during the early stages of ACI is usually recommended. While this seems counterintuitive, some studies have shown either no benefit or negative outcomes when patients are fully fed in the first week or two of acute illness.4 Intensive medical treatments (including medications) and organ dysfunction also influence nutrient needs and may hinder the ability to provide sufficient nutrition. Ultimately, clinical judgement in the application of established guidelines is needed to individually tailor nutrition therapy to meet the unique needs of each patient.

Feeding challenges in the ICU are numerous, even beyond the early stages of critical illness. Hypotension is common, and many patients require vasopressor medications to maintain adequate blood pressure to ensure sufficient blood flow to vital organs such as the brain, heart, and lungs. Initiation of EN may be delayed in these patients who are hemodynamically unstable, as well as patients with major gastrointestinal injury or dysfunction. Other challenges include frequent feeding interruptions due to procedures, actual or perceived intolerance, and nursing care.

Nutrition Therapy in CCI

Feeding challenges, paired with intentional underfeeding in the early stages of critical illness, result in energy and protein deficits. Critically ill patients operate at an increasing nutritional deficit the longer their hospital stay, therefore those with CCI are most significantly affected. Inadequate intake for prolonged periods, combined with increased nutrient needs, often results in malnutrition. Even when energy and protein intake is seemingly adequate, malnutrition often still occurs due to the catabolic state characteristic of critical illness. Muscle loss is pervasive due to catabolism and inactivity; on average, ICU patients lose almost 2% of their muscle mass each day in just the first week of critical illness, and the rate of ICU-associated weakness has been reported to be nearly 50%.5 Many patients lose a significant amount of total body weight during their hospital stay, and of those who do, only 50% to 70% return to their preadmission weight one year after discharge. Additionally, regained weight is most predominantly fat, not muscle mass.6 Malnutrition is associated with its own range of complications which impair the patient’s ability to recover from critical illness.

The shift from ACI to CCI is generally characterized by a gradual reduction of catabolism and eventual transition to an anabolic state. There are no universally recognized parameters to definitively identify when a patient has transitioned to an anabolic state. Biochemical inflammatory markers, such as C reactive protein, can provide some guidance as to the patient’s metabolic state. Especially when energy intake is limited in the initial stages of ACI, it is important to frequently reassess nutrient needs and increase nutrient provision when appropriate to minimize nutritional deficits. As the patient’s medical status stabilizes and inflammation and catabolism begin to improve, energy and protein needs increase to support recovery. However, like ACI, ideal intakes for patients with CCI are unknown and will vary considerably among patients.

Nutrition Assessment

In addition to periodic assessment of energy and protein needs, the RD should complete a full assessment to determine nutritional status and current intake. Validated criteria should be used to diagnose malnutrition. A nutrition-focused physical exam (NFPE) should be performed during the initial assessment and periodically on follow-up visits to evaluate fat and muscle mass and monitor for signs of micronutrient deficiencies. Technological means to assess muscle mass are recommended, although cost and availability of equipment may hinder the use of some methods. Ultrasound and bioelectrical impedance may be more viable options; however, the NFPE is also a valid method to assess muscle mass.7

The environment of care will also dictate the methods available to assess nutrition status. In patients who’ve been discharged home, an in-person visit to a clinic may pose a hardship to many as weakness and limited mobility are common; therefore, remote assessment via a web-based platform or telephone may be necessary. A visual assessment of the patient’s fat and muscle stores, in addition to questions related to their appearance, fit of clothing, and functional status may provide clues as to the presence of muscle and fat loss, although this method has not been validated. Calf circumference has been validated as a proxy measure for muscle mass, so this may be an option in the remote setting if a tape measure is available to the patient.7

After determining the patient’s nutritional status and ascertaining nutrient intake, the RD can develop a nutrition care plan to help support the rehabilitation and recovery process.

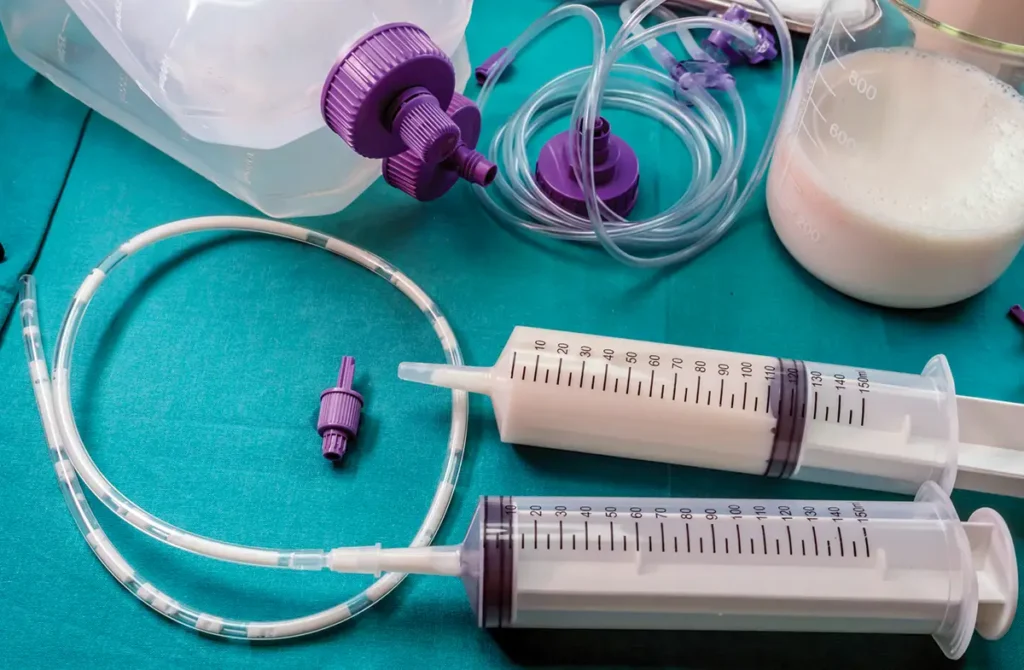

Enteral Nutrition

As many patients with ACI require EN, a key feature of nutrition therapy in CCI recovery is the transition to oral feeding. Dysphagia is common in patients who were intubated, even for short periods of time, due to both the presence of the ventilation tube and general weakness. Many patients with CCI require prolonged mechanical ventilation; in these cases, patients usually receive a tracheostomy, in which the breathing tube is inserted directly into the trachea through an incision in the throat. Mechanical ventilation through a tracheostomy, as opposed to an orally inserted breathing tube, is more comfortable for the patient and eases the weaning process. In some cases, patients may tolerate being off the ventilator for increasing periods of time or can maintain adequate oxygenation with the ventilator at lower settings. In such cases, the patient may tolerate the placement of a valve (called a Passy-Muir Valve) that covers the tracheostomy opening, allowing the patient to speak and swallow.

Whether the patient has been extubated or has a tracheostomy with a Passy-Muir Valve, they should be carefully assessed by a speech language pathologist to determine when they can safely eat and drink. When initiating an oral diet, intake is usually inadequate; research shows intake of 55% to 75% of energy needs and 27% to 74% of protein needs in the early stages of recovery after discharge from the ICU.6 It’s therefore advisable to continue EN to ensure the patient is adequately nourished until they can meet most of their needs through oral intake. Enteral feeding tubes are often removed when the patient is extubated; the need to retain the tube should be communicated with the provider before extubation, if possible. However, removal of the feeding tube is necessary if it was placed orally; in such cases another feeding tube should be inserted nasally after the patient is extubated. If the need for prolonged EN is anticipated, a percutaneous tube should be placed. When an oral diet is started, EN feeding regimens should be modified, such as transition from a continuous to nocturnal infusion schedule, to encourage oral intake.

Oral Intake

When an oral diet is initiated, modified diet textures and thickened liquids are often necessary. However, these alterations may inhibit intake, as some patients find foods with modified textures unpalatable. The RD should work with the food service staff to ensure that the taste and appearance of the food is as appealing as possible. Serving more foods that are naturally of the recommended texture (like pudding or unfruited yogurt for pureed diets) can help. Additionally, these products can also be fortified via calorie or protein modulars to boost intake. Intake of food and fluids should be monitored closely, and the patient should be regularly assessed for signs of dehydration, especially if they’re on thickened liquids and not receiving additional fluid intravenously or through a feeding tube.

Achieving adequate intake via oral diet alone is a challenge in patients with CCI. Poor appetite has been identified as the leading cause of inadequate intake in CCI and can be caused by ongoing inflammation or other metabolic processes, medications, lingering organ dysfunction, and psychological issues. Other common symptoms impacting intake include early satiety, nausea, and taste changes; combined with poor appetite, inadequate intake is common.6 Intake may be further limited due to altered diet textures, therapeutic restrictions, and meals consisting of foods the patient is unfamiliar with or dislikes.

Family or other loved ones may be of great benefit to the nutritional recovery of patients with CCI, as they can bring food from home to help supplement what the patient is receiving in the facility. However, if the patient is on a mechanically altered diet, the speech language pathologist should vet each food item to ensure it is the appropriate texture, and the RD should do the same to ensure the food’s nutritional profile won’t be overtly harmful to the patient (such as very high sodium content in a patient with congestive heart failure). Although sometimes necessary, therapeutic diet restrictions should be avoided whenever possible. The RD can work with the physician provider to ensure medical and pharmacologic care is adequate to control disease complications. For example, adjusting medications to control blood glucose in patients with diabetes may help limit the need for diet restrictions. Short-term nutritional goals should be prioritized; for a malnourished patient with a history of heart disease, encouraging intake via a regular diet is much more important than controlling cholesterol levels via a low-fat diet.

A “food first” approach—increasing meal frequency (adding snacks) and caloric density of meals (adding calorie or protein modulars to foods)—can be successful in increasing nutritional intake. In addition to diet modifications, oral nutrition supplements (ONSs) are a common nutritional intervention, although it’s important to ensure that the patient is actually consuming them. Giving three cartons of an ONS daily doesn’t do the patient any good if they aren’t drinking them. Exploring different products and flavors can be beneficial in improving ONS intake in the case of limited acceptance or “flavor fatigue.” Although product availability may be limited by the facility’s purchasing contracts, exploring different avenues to obtain additional products may be beneficial.

Another factor inhibiting intake is psychological disorders such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD. In addition to an overall severe decline in their general health, dependency on others for basic activities, impaired cognition, pain, and disordered or inadequate sleep contribute to these psychological conditions. 6 This is an often-overlooked aspect of care which should be addressed by a mental health professional. Patient centered care, in which the patient is given autonomy and the ability to participate in decision making, and adjusting medical, nursing, nutrition, and other therapies to accommodate patient needs can also help.

Conclusion

Although awareness of CCI among health care professionals has increased in recent years, additional research and general education on the condition is needed. Specialized nutrition care is required to help improve outcomes and recovery for patients with this debilitating condition.

— Jennifer Doley, MBA, RD, CNSC, FAND, is currently a corporate malnutrition program manager with Morrison Healthcare. She has worked in a variety of clinical care settings, including the ICU and long-term acute care hospital. She is the coeditor of the book Adult Malnutrition: Diagnosis and Treatment.

References

1. Critical care statistics. Society of Critical Care Medicine website. https://www.sccm.org/communications/critical-care-statistics. Updated May 15, 2024. Accessed October 16, 2025.

2. Ohbe H, Satoh K, Totoki T, et al. Definitions, epidemiology, and outcomes of persistent/chronic critical illness: a scoping review for translation to clinical practice. Crit Care. 2024;28(1):435.

3. Nakanishi N, Liu K, Hatakeyama J, et al. Post-intensive care syndrome follow-up system after hospital discharge: a narrative review. J Intensive Care. 2024;12(1):2.

4. Compher C, Bingham AL, McCall M, et al. Guidelines for the provision of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46(1):12-41.

5. Fazzini B, Märkl T, Costas C, et al. The rate and assessment of muscle wasting during critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2023;27(2):2.

6. Moisey LL, Merriweather JL, Drover JW. The role of nutrition rehabilitation in the recovery of survivors of critical illness: underrecognized and underappreciated. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):270.

7. Barazzoni R, Jensen GL, Correia MITD, et al. Guidance for assessment of the muscle mass phenotypic criterion for the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) diagnosis of malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2022;41(6):1425-1433.