Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 17 No. 8 P. 40

Today’s Dietitian speaks with experts about the differing definitions of processed foods, and whether all or some are detrimental to overall health.

Do you advise your clients and patients to avoid processed foods, while suggesting they take advantage of the convenience offered by prewashed salad greens and canned tuna? Trouble is, these mixed greens and canned tuna are processed foods, too.

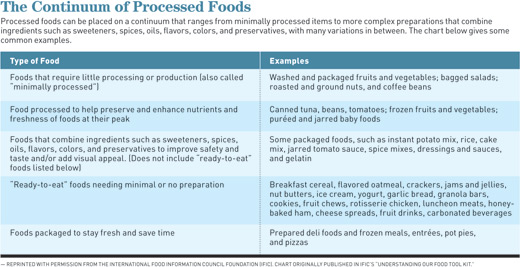

And so are many other foods: from your morning coffee or tea to the frozen berries in a smoothie, and from the yogurt eaten for a snack to the crusty whole grain bread served with dinner. According to the International Food Information Council (IFIC) Foundation, a processed food is any food that’s been deliberately changed from a raw agricultural commodity before it’s available to eat.

But that isn’t necessarily a negative. The Canned Food Alliance (CFA) contends that the blanket statement “avoid processed foods” is shortsighted. “Canned fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins, including tuna, are considered minimally processed and filled with good nutrition and simple ingredients,” says Rich Tavoletti, executive director of the CFA.

“One of the biggest misconceptions about processed foods is the inaccurate belief that processed foods can’t fit into a healthful diet,” says Sarah Romotsky, RD, associate director of health and wellness at the IFIC. “According to the 2014 IFIC Foundation Food & Health Survey, three-quarters of Americans agree that food processing can help food stay fresh longer; however, only one-half of Americans agree that processed foods can contain nutrients we need for a healthful diet.”

Clashing Definitions

Perhaps part of the reason for these disparate responses is that many Americans don’t view foods such as yogurt, frozen berries, and prewashed salad greens as processed.

“Almost all foods are processed in some way or another, but the degree of processing varies enormously, from washing apples to converting potatoes to chips,” says Marion Nestle, PhD, MPH, the Paulette Goddard Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health at New York University, and author of Food Politics: How The Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health. “So ‘processing’ depends on how it’s defined along that continuum. No wonder it’s confusing.”

Consumers often think of highly processed foods whenever the word “processed” comes to mind. According to Judy Simon, MS, RD, CD, CHES, an outpatient dietitian at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle, her clients tend to define processed foods as foods that come from a box, can, or are premade such as fast foods. They also describe processed foods as containing unwanted chemicals.

“We could say anything’s processed that’s not in its original form,” says Mary Purdy, MS, RDN, a private practice dietitian and adjunct clinical faculty member at Bastyr University in Seattle. “That would include applesauce, baby food, even turning olives into olive oil. Simply speaking, it’s just an alteration of that food. But I think what’s problematic is the alteration of the food to the point that the nutritional content of the food is compromised. We’re seeing so much of that in the diet, and it’s compromising health.”

“Giving advice to ‘avoid processed foods’ is telling consumers that any item that’s packaged or not in its original raw state is detrimental to their health,” says Marianne Smith Edge, MS, RD, LD, FADA, senior vice president of nutrition and food safety for IFIC and a past president of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. “If we truly avoided processed foods, we would eliminate nutritious foods like fortified cereals, milk, or whole grain pasta or bread.”

The IFIC describes processed foods within a continuum (see sidebar), which may offer clarity or further confusion, depending on the point of view.

“IFIC’s continuum completely overlooks the important factor that is ingredient composition of foods,” says Andy Bellatti, MS, RD, a nutrition consultant in Las Vegas. “It also tries to make the industry-friendly argument that roasted almonds and Pop-Tarts are all examples of ‘processed foods,’ which is a basic, literal, and in no way nuanced way of explaining the concept of processed foods.”

Nestle says, “The idea is to keep the food as close to its state of origin as possible. Minimally processed foods are recognizable for what they are. Heavily or ultraprocessed foods have long lists of mysterious ingredients, usually.”

Those are the foods with which Purdy takes issue. “I kind of feel like the fewer ingredients the better, the more recognizable the better,” she says. “No food should have 17 ingredients in it, unless it’s something like chili. I tell my patients that if you can see that food rotting on your counter within a few days, those are the foods you want to be eating.”

Simon points out that many people have few kitchen skills and have grown dependent on packaged convenience foods. “If I’m working with a woman who feeds her family boxed Hamburger Helper, I might ask her if she would like to try a simple recipe using vegetables, spices, and more whole foods.”

Nutritional Importance

While there has long been confusion and debate over how to define processed food, the issue came to a head last year when the American Society for Nutrition (ASN) published a scientific statement in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, asserting that processed foods are nutritionally important to American diets, and that new technologies should be developed to make them more nutritious.

“Processed foods and whole foods aren’t mutually exclusive,” says Connie Weaver, PhD, head of the department of nutrition science at Purdue University and corresponding author of the ASN statement. She says that a reasonable approach to improving nutritional quality of processed foods is to ensure they include nutrients that should be emphasized and reduce nutrients that should be limited, such as salt, sugar, solid fat, and sodium, as identified by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. And she says technology can help do just that.

Bellatti doesn’t agree, calling this viewpoint myopic. “When we examine nutrition through a reductionist lens of grams of fiber or percentages of vitamins and minerals and ignore actual ingredient lists, it’s easier to make an argument for the ‘healthier’ versions of highly processed foods,” he says. “A serving of 22 almonds doesn’t offer the iron, vitamin A, vitamin D, or vitamin B12 that [a fortified food such as] Froot Loops does. The almonds do, however, have heart-healthy fats and antioxidants without the added sugar or artificial additives.”

History of Food Processing

What many don’t realize is that as soon as our ancestors began to use fire to cook, the sun to dehydrate, and salt to preserve food, food processing was born. In fact, until about 100 years ago, most food processing was done in the home through canning, smoking, drying, fermenting, and salt preserving. These techniques made it possible to have food to eat during the months between harvests. Today, food processing is largely industrialized. Some industrial food processing involves methods that home cooks use, such as freezing, canning, and baking, while others involve more complex methods, such as the development and use of hydrogenated oils, corn syrup, and artificial sweeteners.

Pros and Cons of Processed Food

Unless clients prepare all of their meals from scratch using raw ingredients that they raised or grew themselves, they rely on foods that someone else has processed for them. Food processing makes it possible to put a healthful meal on the table and still meet the other demands of modern life. It also makes the safe preservation, transport, and storage of food possible.

There’s an idea that fresh is best when it comes to produce, but there are several advantages to processing by freezing and canning, especially when using single-ingredient foods such as fruits, vegetables, beans, seafood, and lean proteins. For example, these methods can lock in nutrients at their peak and provide year-round access.

“Food isn’t nutritious unless it’s consumed, and fresh isn’t always available, so the more we can recommend a variety of healthful options that are easy, affordable, and nutritious, the better,” Tavoletti says.

Simon says that while calorie-dense, nutrient-poor, heavily processed foods can promote obesity and chronic disease over time if eaten to the exclusion of fruits and vegetables, she agrees there are benefits to eating minimally processed foods. “Many of us are very busy and not always near a kitchen, so the convenience of individual yogurts or cheese sticks provide a healthful snack or meal. Canned tomato sauce provides more lycopene than fresh tomatoes, and yogurt or kefir provides probiotics that we wouldn’t find in milk.”

Purdy says fermentation and culturing are processes, but they enhance the benefits of the food. “This kind of processing gives us additional value,” she says. “It makes the food easier to digest. It enhances nutrient availability, and it provides us with beneficial bacteria, which is good for the gut.”

On the other hand, there’s good reason for the advice to limit processed foods such as refined grains that have been stripped of their fiber and many other nutrients. “It’s important to remember that nutrients act in a synergistic fashion within their original food matrices,” Bellatti says. “For instance, we know that when vitamin E is consumed in its whole food form (mainly nuts and seeds), other nutrients and phytochemicals in these foods act in tandem to confer health benefits. When vitamin E is isolated, it isn’t effective.”

Adrien Paczosa, RD, LD, CEDRD, owner of iLivewell Nutrition Therapy in Austin, Texas, says all food provides some type of energy and benefit, and any food can be potentially detrimental to health. “As nutrition experts, our job is to guide clients on how the food can be used to reach their overall health goals,” she says.

Purdy says she sees foods containing low-quality ingredients, such as chips, candy bars, sodas, and frozen meals, as the real concern. “So many processed foods have long lists of ingredients that read like a science experiment. Your great-grandmother probably wouldn’t recognize them—things that are added to preserve the shelf life, such as additives and preservatives. Those [foods] don’t have a welcome place in the diet on a regular basis.”

Bellatti says, “The best available food options are always those that are minimally processed, as these will always provide fewer constituents to limit and more nutrients to encourage for the calories consumed.”

Counseling Clients and Patients

Due to the confusion surrounding the definition of processed food and how to gauge a food’s healthfulness, the ways in which dietitians advise patients varies.

“I encourage my patients to focus on inclusion of whole foods in their diet for taste, health, and environmental benefits,” Simon says. “Some of my patients are very interested and motivated to eat real whole foods most of the time. Others are much more familiar with heavily processed foods, and they may be moving toward adding any whole food into their diet.”

Simon also says she looks at processed foods on a spectrum. “They aren’t all bad, and I suggest minimally processed foods as much as possible.” Some of her patients, such as athletes and people recovering from eating disorders, have high-caloric needs, and it can make sense to include energy bars or protein shakes that have short, real-food ingredient lists.

“I always prefer to focus on whole, nutrient-dense foods, so I recommend limiting processed foods as much as possible,” says Monica Lebre, MS, RDN, LDN, a private practice nutrition counselor and consultant in Medway, Massachusetts. “However, at times, realistically some processed foods can certainly fit into a healthful diet.”

Paczosa says that in her practice, she meets clients where they are in their food journey. “If someone has been purchasing a certain product for a while and wants to make changes, our job is to guide them along in a positive way without any shame around their choices.”

While it’s important to meet clients and patients where they are, Bellatti says ultimately it’s a dietitian’s job to help them achieve better health over time. “Over the years, I’ve seen that the patients who decrease their intake of highly processed foods, cook more at home, and implement more whole foods into their diets tend to have better health outcomes.” When dietitians equalize the food playing field by saying “all foods fit,” it helps no one, Bellatti says. “A much better approach is to talk about foods that fall into these categories: ‘Eat on a daily basis,’ ‘Eat no more than two or three times a month,’ and ‘Eat rarely, if at all.’ At least that gives weight to actual nutrition science. ‘All foods fit’ operates from a framework where Pop-Tarts, lentils, donuts, and carrots are all supposed to be equal.”

Future Directions

This debate will continue. Since the ASN statement was published, Weaver says there has been more conversation about the role of processed food in nutrition among health care professionals in public health, food science, media, and school foodservice. “I hope the national dialogue among professional groups eventually leads to a greater involvement that includes the government, consumer groups, and others who can influence the food supply and availability.”

According to Bellatti, simply improving highly processed foods isn’t the best solution for America’s nutritional inadequacies. Nutrition professionals should be asking why, if whole, real foods offer nutrients in abundance, is a large percentage of the American population low in key nutrients? “The answer would at least begin to shed light on systemic, widespread issues that affect public health—and we might realize that the solution requires more than sprinkling isolated nutrients into highly processed products.”

Nestle says that the makers of processed foods are in retreat because food and health advocates have been successful in changing consumer views about these foods. “The food industry’s job is to sell foods, and companies hire people—lots of them—to figure out how to market whatever the product is. Many people want to eat foods they can recognize and are looking for those that are as minimally processed as possible.”

— Carrie Dennett, MPH, RDN, CD, is the nutrition columnist for The Seattle Times and speaks frequently on nutrition-related topics. She also provides nutrition counseling and therapy via the Menu for Change program and at Northwest Natural Health, both in Seattle.