Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 19, No. 5, P. 36

Here’s how to identify food insecure clients and get them the assistance they need.

“You should eat fish twice per week to get your omega-3s.”

“I recommend eating a diet focused on fresh fruits and vegetables in a variety of colors.”

“Try switching to whole grain products.”

How many times have nutrition professionals made these broad recommendations without giving much consideration to the practical limitations some patients may face in achieving these goals? Roughly one out of eight (12.7%) American households is food insecure,1 which is defined as a “household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food.”2 Food insecurity can result in psychological distress and physical health consequences, including obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. To make recommendations compassionately tailored to patients affected by food insecurity, nutrition professionals must develop the personal awareness and professional skills necessary to identify those who are food insecure while understanding how food insecurity shapes patient behaviors and health risks.

Prevalence in the United States

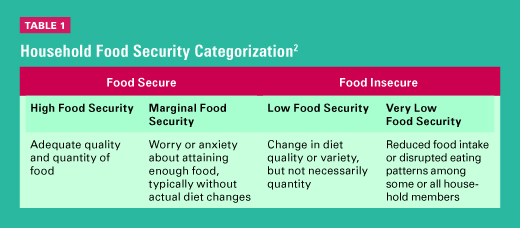

Annual estimates of food insecurity in the United States are obtained through a supplemental survey of the monthly Current Population Survey, conducted by the US Census Bureau and sponsored by the Economic Research Service of the USDA.1 Household food security is classified into four categories: high food security, marginal food security, low food security, and very low food security (See Table 1).2,3 Households reporting three or more food insecure conditions, such as worrying that food will run out before they have money to buy more or eating less because there isn’t enough food, are classified as food insecure.1 A common misperception held by the general public and some health professionals is that food insecurity is synonymous with hunger. Rather, “hunger is an individual-level physiological condition that may result from food insecurity” and is usually experienced by those with very low food security.2 Affecting a greater share of the population than hunger, food insecurity is a broader social and economic household condition that’s also associated with negative physical and mental health consequences among household members.

In addition to the four categories of food security at the adult level, households with children can be further classified as having food insecurity at the child level.1 Adult household members often will preserve a child’s food supply by eating less themselves, but children living in households with very low food security among adults are more likely to experience a reduced quality or quantity of food intake and be food insecure themselves. About 13.1 million children live in very low or low food security households, and about one-half of these children experience food insecurity at the child level.1

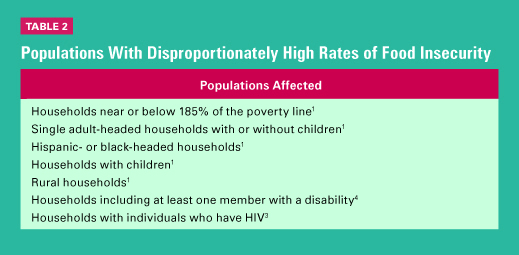

Certain populations experience higher rates of food insecurity due to socioeconomic, food accessibility, or disability-related factors.1,4 (See Table 2 on page 39 for a list of households at the highest risk of food insecurity.)

Health Consequences of Food Insecurity

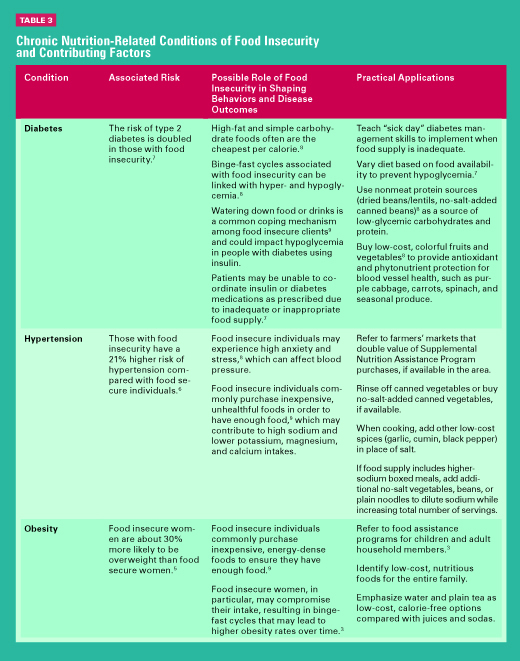

Alongside food insecurity comes possible clinical and behavioral consequences. Food insecurity places clients at higher risk of nutrition-related diseases typically associated with excess calorie, carbohydrate, and fat intake such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, as well as those typically linked with select food group inadequacies, such as anemias, low bone density, and other micronutrient deficiencies.3 The association between food insecurity and obesity is commonly called the hunger-obesity paradox and may be explained by high intakes of low-cost, calorie-dense foods; cyclical food restriction; and the resulting metabolic responses to these dietary patterns.5 Food insecurity has been found to be associated with both diabetes and hypertension, as well as with poor diabetes management.6,7 Diabetes and obesity are more apparent among food insecure women than other household members. This female burden of food insecurity may be a result of female caretaker roles, whereby women choose to compromise their own food intake to ensure a more adequate food supply for other household members.3 Some of the behavioral consequences related to food insecurity include high anxiety and stress,8 binge-fast cycles, and watering down food or drinks to increase quantity.8,9 (Table 3 illustrates several of the chronic conditions associated with food insecurity, how food insecurity may play a role in disease development and management, and strategies for tailoring nutrition recommendations accordingly.)

Nutrient deficiencies can occur in both food insecure adults and children, but deficiencies are especially problematic when they affect growing children or pregnant women. One of the most frequent nutrient deficiencies among food insecure children is iron deficiency, which, along with other common deficiencies, can affect cognitive, emotional, and physical development.3 In general, food insecure individuals’ diets are deficient in some nutrients and food groups such as vegetables, especially dark green, leafy vegetables.3 Dietitians working with food insecure or potentially food insecure clients should evaluate for possible deficiencies and inadequate intake of individual food groups when applying the nutrition care process.

Identifying Food Insecure Patients

Both inpatient and outpatient settings can implement routine food insecurity screenings, which can be quickly administered in oral or written form. Social workers, front desk personnel, dietetics staff, and care coordinators, among others, all can administer food insecurity screenings. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (the Academy) endorses the following single-item screening tool.3

1. Which of these statements best describes the food eaten in your household?

[ ] Enough of the kinds of food we want to eat

[ ] Enough but not always the kinds of food we want to eat

[ ] Sometimes not enough to eat

[ ] Often not enough to eat

Any response other than “enough of the kinds of food we want to eat” indicates potential food insecurity.

In addition, dietitians can use the following two-item survey with 97% sensitivity and 83% specificity for food insecurity, endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics10 (AAP) and AARP11 to screen patients for possible food insecurity:

1. Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.

[ ] Yes [ ] No

2. Within the past 12 months, the food we bought just didn’t last, and we didn’t have money to buy more.

[ ] Yes [ ] No

A “yes” response to either question indicates potential food insecurity and should be explored further.

Recommendations of Top Health Organizations

The Academy states that dietitians and dietetic technicians are “uniquely positioned to make valuable contributions through provision of comprehensive food and nutrition education [and] competent and collaborative practice” for food insecure populations.3 In addition, the Academy’s Second Century Initiative focuses on addressing global access to healthful food, malnutrition, and chronic disease, which includes food insecurity as a growing nutrition trend.12

The AAP and AARP recommend universal food insecurity screenings for all pediatric populations and all older adults,10,11 while some diabetes providers have called for selective screening for all individuals with diabetes with risk factors or those seeking care in safety net organizations.8 Based on these recommendations, nutrition professionals are ideally suited to collaborate with pediatric, geriatric, and diabetes medical providers that have identified a food insecure patient; MNT visits provide the opportunity for a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s household food situation and the development of a nutrition care plan in the context of existing medical needs. Likewise, dietitians receiving referrals for general nutrition therapy from these providers should implement food insecurity screenings when indicated if this information isn’t part of the nutrition referral.

Applying the Nutrition Care Process

The Nutrition Care Process consists of assessment, diagnosis, intervention, and monitoring and evaluation, with each step bearing special considerations for food insecure patients. Assessments with food insecure clients should focus on understanding clients’ intake throughout the month, which can vary widely from episodes of binging to hunger,8 and considering client resources, such as access to transportation, healthful food outlets, and kitchen appliances.3 Assigning a nutrition diagnosis for the food insecure patient will be specific to the client’s disease state, most often in the context of limited food access, such as the diagnoses of “inconsistent carbohydrate intake” or “limited access to food” for a patient with diabetes who has uncontrolled blood glucose and an inadequate food supply. Interventions need to consider clients’ individual needs, which could include the realities of prioritizing rent or utility bills above ideal foods (ie, a focus on “survival skills”), and should commonly include referrals to government or community food assistance programs.3 Monitoring and evaluation must be specific to the nutrition diagnosis, and intervention(s) and may involve assessing a client’s successful use of food assistance programs in addition to changes in food security status.

Food insecure clients may experience numerous barriers to implementing nutrition recommendations, which shouldn’t be confused with a lack of desire to change eating habits. During the initial goal setting and reassessment process, dietitians should be prepared to problem solve around these barriers and offer empathetic support. For example, food insecure individuals often go through binge-fast cycles, in which they may eat excessive amounts of high-calorie foods when food is available and then go through times of hunger when food isn’t available.8 In people with diabetes, these cycles can cause hyper- or hypoglycemia.8 Dietitians can teach patients how to be aware of these behaviors and practice mindful eating. In addition, food insecure patients may live in a food desert and lack access to transportation.3 Food deserts are associated with both a lack of healthful food availability and typically high costs of healthful foods.8 Thus, dietitians should be prepared to identify more shelf-stable food options and consider the relative weight of foods for patients who must walk to and from the grocery store. Visiting the communities where patients live and make food purchases will enable nutrition professionals to better relate to patients when establishing eating goals. Lastly, some food insecure households may not be equipped with the appliances or kitchen tools necessary to prepare meals from scratch, which generally cost less than prepared meals.3 Gathering information from the patient on access to kitchen supplies and cooking skills can help with developing realistic goals based on existing patient resources. Example questions that can assist dietitians with conducting a tailored nutrition care plan for food insecure populations include the following:

• How well does this (24-hour recall, food frequency questionnaire, etc) represent how you eat throughout the month? Are there some days or weeks each month when you eat differently?

• Where do you typically do your grocery shopping? Is there a grocery store nearby that sells good-quality and affordable fresh foods?

• What might keep you from making healthful meals at home, and how can we overcome those barriers? Is it lack of time, lack of cooking utensils/appliances, or not enough money in the food budget?

• Many people use Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, WIC, free school breakfast and lunch programs, or food pantries as resources for additional food. Have you currently or previously used any food assistance programs?

• How confident are you that you can implement the changes we’ve discussed today? Do you feel you can easily access, afford, and prepare these options, or would you like us to spend some time discussing other options that we can try instead?

Qualified for the Task

Nutrition professionals are uniquely positioned to help reduce the health disparities affecting food insecure populations. A compassionate approach to the nutrition care process requires an appreciation for the constraints food insecurity can place on household food choices and eating behaviors, a resourceful and creative attitude for identifying practical solutions for nutrition problems, and an empathetic, nonjudgmental approach when evaluating nutrition care plan progress. Because dietitians in nearly all settings may encounter clients who are food insecure, maintaining professional awareness of this problem can better position nutrition professionals as essential resources for the care of populations in need.

— Kayla Castleberry, BS, is an MPH candidate at Oklahoma State University. She has developed expertise in the delivery of community-based nutrition services for low-income people living with HIV/AIDS and in conducting research to identify the current and potential roles of US food banks in healthful food distribution.

— Marianna Wetherill, PhD, MPH, RDN-AP/LD, is an assistant professor in the departments of health promotion sciences and family and community medicine at the University of Oklahoma-Tulsa. Her research expertise includes the development of clinical and community-based interventions for food insecure populations that address health disparities by improving healthful food access and facilitating health behavior change.

References

1. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2015. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/err215/err-215.pdf. Published September 2016.

2. Coleman-Jensen A, Gregory C, Rabbitt M. Definitions of food security. USDA Economic Research Service website. http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx. Updated October 4, 2016. Accessed November 18, 2016.

3. Holben DH; American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: food insecurity in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(9):1368-1377.

4. Coleman-Jensen A, Nord M. Food insecurity among households with working-age adults with disabilities. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/err144/34588_err_144_report_summary.pdf. Published January 2013.

5. Scheier LM. What is the hunger-obesity paradox? J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(6):883-885.

6. Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304-310.

7. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 1):S1-S112.

8. López A, Seligman HK. Clinical management of food-insecure individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2012;25(1):14-18.

9. Weinfield NS, Mills G, Borger C, et al. Hunger in America 2014: National report prepared for Feeding America. http://help.feedingamerica.org/HungerInAmerica/hunger-in-america-2014-full-report.pdf. Published August 2014.

10. O’Keefe L. Identifying food insecurity: two-question screening tool has 97% sensitivity. AAP News: American Academy of Pediatrics website. http://www.aappublications.org/news/2015/10/22/FoodSecurity102315?utm_source=

TrendMD&utm_medium=TrendMD&utm_campaign=AAPNews_TrendMD_1. Published October 22, 2015.

11. Pooler J, Levin M, Hoffman V, Karva F, Lewin-Zwerdling A. Implementing food security screening and referral for older patients in primary care: a resource guide and toolkit. AARP website. http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/aarp_foundation/2016-pdfs/FoodSecurityScreening.pdf. Published November 2016.

12. The second century of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation website. http://eatrightfoundation.org/why-it-matters/second-century/. Accessed November 18, 2016.