By Hadley A. Turner

For many, it’s common knowledge that what a woman consumes during pregnancy affects her health and that of her baby both pre- and postnatally. Women are advised to avoid raw eggs and sushi to reduce the risk of foodborne illness, fish containing high levels of methyl mercury (eg, swordfish, shark, and tilefish), and alcohol, while limiting caffeine and nitrates, commonly found in processed meats.1

But what about foods or nutrients pregnant women should eat? As dietitians know, the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) for many nutrients change when a woman becomes pregnant. The intake of one particular nutrient that increases significantly in pregnancy is iron. According to the DRI, healthy females aged 19 to 50 should get 18 mg of iron daily. For pregnant women in the same age range, the DRI for iron is 27 mg per day, a 50% higher goal.2

A Global Concern With Far-Reaching Consequences

The World Health Organization estimates that 30% of people internationally suffer from an iron deficiency, making it the most prevalent health condition in the world.3 Iron deficiency is unique because of its universality; it affects citizens in both developed and developing nations relatively equally when compared with other nutrient deficiencies. Most experts attribute the deficiency’s prevalence to poor diets (ie, the typical Western diet) in developed countries and poverty and lack of education in developing countries.3

Women and children are most at risk of iron deficiency, and a lack of adequate iron during pregnancy can have serious effects in children in utero and neonatally. A recent study published online in November 2015 in the journal Pediatric Research showed poor cognitive and motor skill development due to improper gray-matter organization in children who weren’t exposed to enough iron prenatally.4 While this study examined iron deficiency through an unprecedented use of neonatal MRI, the body of evidence on the effects of iron deficiency during pregnancy seems to support similar conclusions.

In a 2013 literature review of the topic, Radlowski and Johnson note that studies support the importance of iron for proper brain function, particularly the development of the hippocampus (responsible for memory formation and emotional regulation). The fetal brain experiences a growth spurt in the final trimester, and the neonatal brain relies on iron stores obtained in utero to sustain growth through the first six months of life, after which infants’ bodies can better regulate their own iron. As such, consistent and adequate iron intake throughout pregnancy is essential.5

It comes as no surprise, then, that iron-deficient children tend to suffer from learning and behavioral problems. Even worse, a lack of development prenatally and at the beginning of life often affects children for the rest of their lives. Children born iron-deficient show abnormal cognitive development into their late teens and often end up giving birth to iron-deficient children themselves due to a cycle of lack of education.5

Increasing Dietary Intake

Nutrition professionals are in a special position to combat this serious global problem. With such grave potential consequences, it’s of vital importance that dietitians counsel pregnant clients about the necessity of adequate iron intake.

As with other nutrients, food sources of iron are the preferable form of intake. Red meats, especially organ meats such as liver and giblets, often are touted as being especially rich in iron. This is in part because of the absorbability of the heme form of iron found in meat. The body more easily absorbs heme iron, virtually exclusive to meats as a result of the hemoglobin and myoglobin in animal flesh and blood, than nonheme iron, which is found primarily in plant foods.6 However, this doesn’t mean vegan and vegetarian women or those with more plant-focused diets (all growing trends in light of recommendations to limit red meat consumption) are left in the lurch.

According to Virginia Messina, MPH, RD, a plant-based nutrition expert and coauthor of Vegan for Her: The Woman’s Guide to Being Healthy and Fit on a Plant-Based Diet, dietitians needn’t be especially concerned about iron intake in pregnant women who follow a plant-based diet.

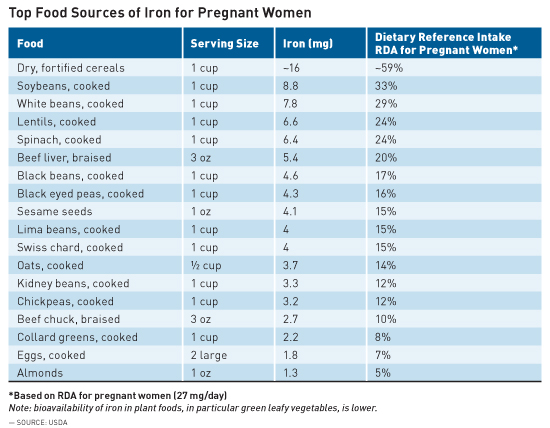

“It’s no more difficult for vegetarian women to meet the [DRI] of 27 mg, and, in fact, might be easier, given the iron-rich nature of plant foods,” Messina says. “Iron is abundant in plant foods, and people are often surprised to know that foods like legumes can contain more iron than meat. Other good sources are whole and enriched grains, nuts and seeds, certain dried fruits, and some leafy green vegetables like spinach and Swiss chard.”

Carrie Dennett, MPH, RDN, CD, founder of Nutrition by Carrie in Seattle, agrees. “We typically think ‘red meat’ when we think ‘iron,’ but while lean meat and seafood are the richest sources of heme iron, you can get nonheme iron from many plant foods,” she says.

While decreased absorbability of nonheme iron is a concern, there are simple ways to increase absorption. Messina recommends consuming a good source of vitamin C in the same meal. In addition, she says, “coffee and tea can reduce iron absorption so, if women are having difficulty meeting iron needs, it’s a good idea to consume these beverages between meals so that they don’t affect the iron in meals.”

Dennett adds that a pregnant woman’s body actually adapts its ability to absorb nonheme iron. “Even though we typically absorb heme iron better than nonheme iron, pregnant women have an increased ability to absorb nonheme iron, which is a testament to the body’s innate wisdom,” she says.

The following table outlines the best food sources of iron for pregnant women.

Supplementation

Regardless of dietary intake, most pregnant women need to rely on a degree of supplementation to meet the increased DRI. “We know that many women, vegetarian or not, don’t meet iron needs of pregnancy which is why iron supplementation is commonly recommended,” Messina says.

According to Dennett, a good portion of iron intake can come from a basic prenatal vitamin. “A good prenatal vitamin will include about 17 mg of iron, which means about 10 mg still needs to come from food, which is easily achievable with a varied, healthful diet,” she says. However, women who become pregnant with a preexisting iron deficiency likely will need extra supplementation beyond that of a prenatal vitamin.

Dietitians should be aware of certain challenges that may arise with iron supplementation. Depending on the dose and type of supplementation, some women experience side effects such as constipation and nausea. “This typically happens at higher doses of supplemental iron (45 mg/day or more), and is also more likely to happen with the sulfate, gluconate, and citrate forms of iron,” Dennett says.

Dennett advises finding the supplementation form and frequency that works best for each individual client, which may require some trial and error. “Some women adapt to the supplements and stop experiencing side effects, but others have to try different formulations to find a good fit,” she says. “Sometimes taking the day’s iron in two doses instead of one or taking it with food does the trick.” Dennett also recommends that clients drink plenty of fluids, increase fiber intake, and be physically active to help prevent constipation.

Ultimately, nutrition professionals must keep in mind the importance of increasing iron intake in pregnant women, which is to avoid the serious risks of iron deficiency for both mother and child. Should there be any problems with supplementation, dietitians must work closely with pregnant clients to ensure a balance between quality of life and adequate iron intake.

“Because it is so critical for maternal and fetal health to maintain good iron status during pregnancy,” Dennett says, “dietitians need to remind clients of that importance while working closely with them to find a way to optimize iron intake while minimizing side effects.”

— Hadley A. Turner is an editorial assistant for Today’s Dietitian.

References

1. Kuzemchak S. A food guide for pregnant women. Parents website. http://www.parents.com/pregnancy/my-body/nutrition/a-food-guide-for-pregnant-women/. Accessed December 10, 2015.

2. Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes (DRIs): recommended dietary allowances and adequate intakes, elements. https://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/DRI/DRI_Tables/recommended_intakes_individuals.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2015.

3. Micronutrient deficiencies: iron deficiency anaemia. World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/ida/en/. Accessed December 10, 2015.

4. Monk C, Georgieff MK, Xu D, et al. Maternal prenatal iron status and tissue organization in the neonatal brain [published online November 24, 2015]. Pediatr Res. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.248.

5. Radlowski EC, Johnson RW. Perinatal iron deficiency and neurocognitive development. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:585.6. Iron we consume. Iron Disorders Institute website. http://www.irondisorders.org/iron-we-consume/. Accessed December 21, 2015.