August/September 2025 Issue

August/September 2025 Issue

Dietitians and Human Trafficking

By Christen Cupples Cooper, EdD, RDN

Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 27 No. 7 P. 16

A Call for Dietetic and Continuing Education

The definition of human trafficking (HT), as defined by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, is “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability, or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.”1

HT is one of the fastest growing global enterprises, involving over an estimated 50 million women, men, and children in nearly every country of the world.1,2 This is considered a low estimate among law enforcement and researchers alike.1,2 The United States is one of the top three nations where trafficking occurs, along with the Philippines and Mexico.3

HT is not a distant phenomenon in a place overseas, but can be found right here at home. Eighty-three percent of trafficked individuals in the United States are US citizens.4 Types of HT encompass three major types: sex, labor, and human organ trafficking.5 Experts believe that sexual exploitation is the most common form.1 Sex traffickers may recruit women or men by promising them a better future or jobs as models, nannies, or factory workers.5 Children are at the highest risk of being trafficked because of their high price on the sex trade and due to their defenselessness.6 Sex traffickers use not only personal contact but also gaming and other online venues for “grooming” (luring and convincing) potential victims. Children with a history of sexual abuse, life in the foster care system, and neglect are at the highest risk for becoming victims of trafficking, as traffickers prey on kids’ hopes, dreams, and naïveté.7,8 Another top form of trafficking is labor exploitation. Individuals can be lured into trafficking by promises of jobs in custodial services, restaurants, agriculture, construction, hospitality, and domestic services.9

Knowing the Signs

The first symptoms trafficked individuals present with are normally malnutrition and dehydration, leading to fatigue, chronic pain, dental problems, or bone damage, and even death.10 Commonly, due to their abuse while in captivity, they also may struggle with psychological, physical, sexual, and/or drug and alcohol abuse.10 Psychological abuse is present in almost all trafficking cases, including tactics such as sleep and food deprivation, physical restraint, torture, physical attack, and health care deprivation.10 Physical abuse is also commonly associated with HT.10 Other common illnesses with which HT individuals commonly present include sexually transmitted infections, substance overdoses, chronic pain, and fractured bones.10 Yet others include depression, PTSD, and anxiety.11 There are also many directly nutrition-related conditions that regularly affect HT individuals, including weight loss, vitamin D deficiency, low albumin levels, dehydration, malnutrition, alopecia, and even eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa.12

In general, human traffickers often allow individuals to seek medical attention only when an illness prevents them from performing their work.13 Yet, health care providers have rare opportunities to identify trafficked patients, since they are often the first, and sometimes only, professionals that HT individuals have contact with outside of their traffickers. 14 One in eight medical providers will come in contact with a trafficked person, although providers may not have the knowledge or training to recognize the individual’s dire life circumstances or the need to provide law enforcement help and other life-saving resources.15

Due to the manifold adverse health conditions facing HT individuals, a multidisciplinary approach is generally used when caring for HT individuals.16 Recommendations call for treatment using an interdisciplinary, evidence-based approach.16 International health care authorities, including but not limited to the US Department of Health and Human Services, Institute of Medicine, the World Health Organization, and Health Canada, promote interprofessional care (interprofessional team [IPT] intervention) for patients across the health care needs spectrum, including for HT.17

The Knowledge Gap

Research performed with physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, emergency medicine specialists, and others suggest that although team care is evidence-based and shows the best outcomes,18 many clinicians lack knowledge, confidence, and therefore competence in working with this important population. Fortunately, research suggests that even basic professional development can significantly impact clinicians’ HT knowledge and ability to spot and care for HT individuals. The American Medical Association suggests that “Grand Rounds-style didactics and online training have shown promising results in increasing clinician knowledge of HT for medical students and physicians.”18,19 Some topics they suggest including in training are definitions of trafficking, scope and scale of the problem, prevention, health consequences, and a trauma-informed, multidisciplinary approach to identification based on trafficking indicators. Others include resources for response at the national level, such as the National Human Trafficking Resource Center hotline, and the local level, such as hospital or clinic social work services, resources for shelter, substance abuse treatment, or legal services, based on survivor needs.19

A study by McAmis and colleagues, published in 2022, surveyed 6,603 health care providers, including physicians, medical students, nurses, nurse practitioners, nursing students, paramedics, social workers, residents, and physician assistants.20 Only 42% of all providers reported having received HT training, with 93% reporting that they would greatly benefit from training. Health care workers also lacked general HT knowledge and were unfamiliar with resources and nonmedical assistance available to HT patients.20

In a study by Chisolm-Straker and colleagues in 2012, only 4.8% of New York City emergency medicine professionals reported feeling confident in their ability to identify victims of HT.21 A 2023 narrative review of HT and health care, published in the International Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Research by Charles and colleagues, 22 suggested that nurses, who are on the front lines of acute patient care, lacked confidence in HT knowledge, skill, and information about referring patients to other health care professionals.22

Training for Providers

Several frameworks for HT training have been recommended by different health care organizations. The American Medical Association asserts that such training must be informed by a human rights–based framework, with the core concept of “strengthening the capacities of rights holders (the trafficking survivors) to secure their rights.”23,24 This includes a trauma-informed, victim-centered, culturally relevant, evidence-based, gender-sensitive approach.25,26 Richie-Zavaleta and colleagues’ 2021 study suggested relying on methodically gathered recommendations from sex trafficking survivors who had received medical care during their time in captivity, using a mixed-methods design.25 Twenty-two individuals residing in San Diego and Philadelphia were interviewed, expressing the following three themes that translated to their proposing a model entitled Compassionate Care:

1. the importance of spotting red flags;

2. the need for supportive health care practices; and

3. the need to build resources around actual patients’ recommendations for compassionate care, trust building, rapport, and hope.25

This model may serve as a basis for future professional development. Dietitians can take leads from victims themselves and other professionals in building our skills and talents into interprofessional continuing education on HT. RDNs can thereby assist victims and elevate our profession as integral IPT members caring for this important and vastly underserved population.25

While the extant literature on health care for HT individuals discusses the role of IPTs consisting of a physician, social worker, psychologist, and nurses,26 it does not contain any evidence that RDNs are routinely included. Given the plethora of nutrition-related health conditions trafficked people face, it is abundantly clear that RDNs should serve as critical participants on IPTs serving HT victims.

Seminal Study: Cooper & McRoberts (2024)

Only one study, by RDNs Cooper and McRoberts, has explored RDNs’ knowledge of HT and the role that they may play in assisting HT victims, confidence in knowing how to react and treat HT victims as part of IPTs, perceived barriers to assisting HT individuals, and preferred modes of continuing education. It also explores how the nutrition and dietetics professions’ Code of Ethics and Scope of Practice, and Standards of Professional Practice support RDNs’ education on and involvement on IPTs treating HT individuals.27

The authors received permission to revise for RDNs a survey by Ross and colleagues,28 “Human Trafficking and Health: A Cross-Sectional Survey of NHS Professionals’ Contact With Victims of Human Trafficking,” which was designed for allied health professionals. The original instrument was modified to contain questions appropriate for RDNs to ascertain their knowledge about potential nutrition-related issues of HT individuals, identify how many RDNs have ever served as members of IPTs caring for HT individuals, identify barriers that have prevented RDNs from becoming involved with this vulnerable population, and learn RDNs’ preferred mode of professional development on this topic. The modified questionnaire, “Knowledge of Human Trafficking and the Role of a Registered Dietitian/Registered Dietitian Nutritionist,” was sent to RDNs who are members of Indiana Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Women’s Health Dietetic Practice Group, and dietetic preceptors affiliated with Ball State University who, after viewing the purpose and unfamiliar nature of the topic of the research, agreed to participate. Of the 241 respondents, 96% were female and 4% were male. Ninety-four percent of the RDNs reported as Caucasian, 0.9% as American Indian or Alaska Native, 0.4% as Asian, and 2.6% as Black or African American. Two percent indicated their race as “other,” with seven RDNs choosing not to answer. One-quarter of the RDNs reported as under the age of 30, 30% were between the ages of 30 and 44, 22% were between ages 45 and 59, and 22% were 60 or older.27

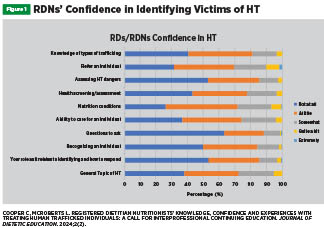

Knowledge, Confidence, and Experience

General knowledge about HT between RDNs’ age groups was significantly different, with those aged 30 to 44 scoring the highest, followed by those under 30 years and those over 60. RDNs aged 45 to 59 scored the lowest. In terms of years of practice, the highest scorers were those with three to five years of employment, followed by those with one to two years. RDNs with six to 10 years and those with more than 10 years scored lowest on knowledge about HT, with a significant difference between groups. RDNs were also asked: “What conditions are seen in HT individuals that nutrition intervention could help treat?” Correct responses included malnutrition, dehydration, weight loss, pregnancy, and HIV/AIDS are common nutrition-related conditions seen in HT individuals. Most RDNs were able to correctly identify these conditions. RDNs were asked to identify their confidence regarding knowledge of HT, caring for a trafficked individual, and identifying and responding to such individuals. About two-thirds of RDNs indicated “not at all” confident in asking questions to better identify HT, assessing dangers, and their specific role as it relates to identifying and responding. Overall, most RDNs “were not at all” to “a little confident” regarding HT-related topics.27

Despite the reported lack of knowledge and confidence, 92% of respondents believed that our profession has a role to play in spotting and assisting HT victims, listing reasons such as RDNs’ abilities to evaluate and help to treat malnutrition and dehydration. However, fewer than 30% reported that they believed that they may have worked with an HT victim in the past. RDNs that reported possible experiences came from a variety of RDN roles, including foodservice, community, and clinical work, detention centers, and faith-based organizations. Those who responded that they had suspected trafficking in a patient(s), less than three-fourths reported that they worked as an RDN on IPT care for the patient(s), with two-thirds indicating that a doctor was on the team, along with a social worker and nurse. Of this group, about one-third of RDNs suspected sex trafficking for a patient. A smaller percentage of suspected cases of labor or domestic work trafficking in patients. The vast majority of RDNs reported that they had not encountered nor suspected any HT victims due to a lack of defined cases in the workplace, working in a nonclinical setting, not having been included in team care, lacking access to detailed patient history, and working in a school or rural setting or a business setting.

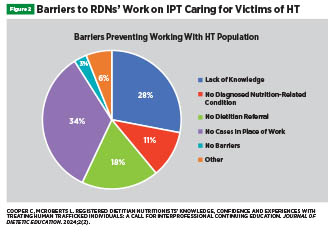

RDNs listed barriers to their opportunities to work with trafficked patients as a lack of cases in the workplace, as well as a lack of knowledge about spotting and treating such patients.27 The top barrier listed by most RDNs in the study was a lack of training/education on HT and how to spot, assist, and treat victims. Nearly 90% of RDNs indicated that their preferred training format would be recorded webinars, video training/scenarios, and case studies. Fewer preferred in-person training.27

Ethical Obligations

The Code of Ethics for the Nutrition and Dietetics Profession (2018) as well as the RDN Scope and Standards of Practice (2024) include principles and standards directly applicable to RDNs’ involvement in caring for HT individuals.29,30 Demonstrating the standards of competence and professional development in practice, professionalism, social responsibility, and justice all dovetail with the role RDNs can play in treating HT individuals.

The Standards of Practice and the Standards of Professional Performance for RDNs support the profession’s unique skills in helping a wide variety of patients and offer “flexible boundaries that [are] defined by the individual RDN’s education, training, credentialing, experience, and demonstrated competence.”30 The Standards also underscore that RDNs “are an integral part of interprofessional teams in healthcare, foodservice management, education, research, and other practice environments.”30 The Standard of Practice 7 particularly pertains to RDNs’ care for HT individuals, as it includes the vital parts of the Nutrition Care Process: Nutrition Assessment, Diagnosis, Intervention/Plan of Care, Monitoring and Evaluation.30

Implications for Practice

The Nutrition Focused Physical Exam, which helps determine patients’ nutritional health status, can serve as a valuable tool RDNs can bring to helping HT patients. This procedure involves several evaluative steps that are not performed by other health care professionals. The procedure involves evaluating muscle grip strength; scalp, mouth, skin, and nail health; appearance and feeling of different body parts, including the arms, legs, chest, back, and face; and signs of fluid retention or dehydration. This skill can help elevate and support the importance of the profession by giving RDNs a unique role in working on IPTs treating HT patients. Not only continuing education but also our foundational nutrition and dietetics education curricula at the undergraduate and graduate levels can help train students in HT. Courses such as Nutrition Assessment and supervised practice experiences may offer opportunities to meet standards by working on simulated or traditional case studies involving HT individuals.

RDNs, with proper education/continuing education, may play a vital role in spotting and treating HT individuals. The profession is well-suited to treat some of the most immediate health threats to HT patients, including malnutrition and dehydration, eating disorders/weight loss/gain, and MNT for conditions such as pregnancy, wounds, burns, and HIV/AIDS. Further research is needed to expand the body of literature on RDNs working with HT individuals. However, the current highlighting of HT as a serious crime and human rights violation can serve as a call to action for RDNs to partner with allied health profession to partner with allied health professions to increase knowledge, experiences, and confidence in spotting and treating HT individuals.

— Christen Cupples Cooper, EdD, RDN, is founding director of Pace University’s Coordinated MS in Nutrition and Dietetics Program in Pleasantville, New York. She is an active researcher on human trafficking and a founder of Pace University’s chapter of the Department of Homeland Security’s Blue Campaign, which brings awareness to all people about human trafficking. She also researches sustainable agriculture and the future of food.

References

1. 50 million people worldwide in modern slavery. International Labour Organization website. https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/50-million-people-worldwide-modern-slavery-0. Published February 1, 2024. Accessed June 11, 2024.

2. 2018 US nNational hHuman tTrafficking hHotline sStatistics. Polaris Project website. https://polarisproject.org/2018-us-national-human-trafficking-hotline-statistics/. Published 2018.

3. 2019 trafficking in persons report. US Department of State website. https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-trafficking-in-persons-report/. Published 2019. Accessed June 10, 2024.

4. Banks D, Kyckelhahn T. Special report: characteristics of suspected human trafficking incidents, 2008-2010. US Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics. April 2011.

5. What fuels human trafficking? UNICEF website. https://www.unicefusa.org/stories/what-fuels-human-trafficking. Published January 13, 2017. Accessed June 11, 2024.

6. Li M. Did Indiana deliver in its fight against human trafficking: a comparative analysis between Indiana's human trafficking laws and the international legal framework. Indiana International & Comparative Law Review. 2013;23:277-334.

7. Cullen-DuPont, K. Human trafficking (pp. 3-28). Infobase publishing. Published January 1, 2009.

8. Gardner M, Steinberg L. Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: an experimental study [published correction appears in Dev Psychol. 2012;48(2):589]. Dev Psychol. 2005;41(4):625-635.

9. Clawson HJ, Dutch N, Salomon A, Grace LG. Human trafficking into and within the United States: a review of the literature. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation website. http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/07/HumanTrafficking/LitRev/index.shtml. Published August 29, 2009.

10. Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Watts C. Human trafficking and health: a conceptual model to inform policy, intervention and research. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(2):327-335.

11. Macias-Konstantopoulos WL. Caring for the trafficked patient: ethical challenges and recommendations for health care professionals. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(1):80-90.

12. Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Abas M, Light M, Watts C. The relationship of trauma to mental disorders among trafficked and sexually exploited girls and women. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2442-2449.

13. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. The health risks and consequences of trafficking in women and adolescents: findings from a European study. https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/10786. Published 2003.

14. Baldwin SB, Eisenman DP, Sayles JN, Ryan G, Chuang KS. Identification of human trafficking victims in health care settings. Health Hum Rights. 2011;13(1):E36-E49.

15. Kiss L, Zimmerman C. Human trafficking and labor exploitation: toward identifying, implementing, and evaluating effective responses. PLoS Med. 2019;16(1):e1002740.

16. Ross C, Dimitrova S, Howard LM, Dewey M, Zimmerman C, Oram S. Human trafficking and health: a cross-sectional survey of NHS professionals' contact with victims of human trafficking. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e008682.

17. Stoklosa H, Grace AM, Littenberg N. Medical education on human trafficking. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(10):914-921.

18. Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, Goldman J, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD000072.

19. Titchen KE, Loo D, Berdan E, Rysavy MB, Ng JJ, Sharif I. Domestic sex trafficking of minors: medical student and physician awareness. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(1):102-108.

20. McAmis NE, Mirabella AC, McCarthy EM, et al. Assessing healthcare provider knowledge of human trafficking. PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0264338.

21. Chisolm-Straker M, Richardson LD, Cossio T. Combating slavery in the 21st century: the role of emergency medicine. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):980-987.

22. Charles ML, David M, St Juste M. Perceptions and experiences of registered nurses caring for human trafficking victims in acute care settings: an integrative review. Int J Epidemiol Public Health Res. 2023;3(2).

23. Davis T. Exploring the nature and scope of clinicians obligations to respond to human trafficking. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(1):4-7.

24. About trafficking in persons and human rights. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner website. https://www.ohchr.org/en/trafficking-in-persons/about-trafficking-persons-and-human-rights. Published 2014. Accessed June 9, 2024.

25. Richie-Zavaleta AC, Villanueva AM, Homicile LM, Urada LA. Compassionate Care—going the extra mile: sex trafficking survivors' recommendations for healthcare best practices. Sexes. 2021;2(1):26-49.

26. Sabella D. The role of the nurse in combating human trafficking. Am J Nurs. 2011;111(2):28-39.

27. Cooper C, McRoberts L. Registered dietitian nutritionists’ knowledge, confidence and experiences with treating human trafficked individuals: a call for interprofessional continuing education. J Diet Educ. 2024;2(2).

28. Ross C, Dimitrova S, Howard LM, et al. Human trafficking and health: a cross-sectional survey of NHS professionals’ contact with victims of human trafficking. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008682.

29. Code of Ethics for the Nutrition and Dietetics Profession. Commission on Dietetic Registration, 2018.

30. Commission on Dietetic Registration. Revised 2024 Scope and Standards of Practice for the Registered Dietitian Nutritionist. https://www.cdrnet.org/vault/2459/web/Scope%20

Standards%20of%20Practice%202024%20RDN_FINAL.pdf. Published January 2024.