Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 25 No. 9 P. 42

CPE Level 2

Take this course and earn 2 CEUs on our Continuing Education Learning Library

In his 2021 book, The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World, author Mark Hyman, MD, introduces the pegan diet concept. It’s based on the paleolithic (paleo) and vegan diets, both of which he describes as low in starch, sugar, processed foods, additives, hormones, antibiotics, and GMOs. He says the primary difference is the choice of protein sources, with grains and beans preferred for vegans and meats preferred for paleo supporters. Hyman coined the term “pegan” to represent a plant-rich, whole foods diet that includes concepts from both approaches. In addition to concepts from paleo and vegan diets, the pegan dietary pattern includes an aspect of time-restricted eating (TRE) or intermittent fasting (IF).1

The goal of the pegan diet, according to Hyman, is to lower the incidence of chronic disease in an ecologically sound and sustainable manner.1 The diet has its roots in functional medicine, a medical model focused on how an individual’s unique genetic makeup interacts with their diet, their environment, and their lifestyle to impact health.2,3 This course will explore the science behind the pegan diet principles.

The Paleo Diet

The paleo diet is based on foods that humans consumed in the Paleolithic era, before about 8,000 BC. It includes meat, fish, eggs, vegetables, fruits, roots, and nuts, and excludes dairy, oils, cereals, legumes, salt, and refined sugars.4 The paleo diet concept assumes that human genetic evolution hasn’t kept up as the food supply has changed with the advent of agriculture and then industrialized food.5

The paleo diet is a low-carbohydrate, high-fiber diet with an estimated 35% of energy from carbohydrate, 30% from protein, 35% from fat, and includes 45 to 100 g of fiber daily.4 A modern Western diet has a higher glycemic load, more carbohydrates, less protein, excess saturated and trans fat, insufficient omega-3 fatty acids, lower fiber content, less micronutrient density, higher net acid load, and higher sodium to potassium ratio.5

The nutritional adequacy of the paleo diet may be affected by the elimination of grains, dairy, and legumes.6,7 It’s likely inadequate in calcium and vitamin D and there may be risk of environmental toxicity associated with high fish intake or hyperuricemia, an elevated uric acid level in the blood due to high purine intake.7,8

Proponents of the paleo diet link chronic diseases such as diabetes, CVD, cancer, metabolic syndrome (MetS), and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to consuming foods that humans haven’t evolved to consume.9 Health benefits are related to enhanced satiety, reduced inflammation, weight loss, improvements in the gut microbiome, and greater nutrient density.6

The Vegan Diet

The vegan diet is a type of plant-based diet that excludes all meat, fish, dairy, eggs, and honey.10,11 The fruits and vegetables in a vegan diet yield plentiful dietary fiber, antioxidant compounds, phytochemicals, folic acid, carotenoids, vitamin C, vitamin E, magnesium, and omega-6 fatty acids.10,12,13 Compared with an omnivorous diet, it’s lower in calories, saturated fat, and cholesterol.10,12 Protein averages about 13% to 14% of daily calorie intake.12 Prevalence of vegan diets in the United States is estimated at 2%.12,13 The potential nutrient shortfalls of a vegan diet include vitamin B12, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, iron, zinc, and iodine.10,12 A vegan diet is typically associated with lower plasma vitamin B12 levels and increased prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency. It’s recommended that those following vegan diets consume vitamin B12 fortified foods, fortified nutritional yeast, or a vitamin B12 supplement.10

IF/TRE

IF is an eating pattern characterized by periods of eating alternated with periods of not eating. This allows the body to switch from using glucose as an energy source to using ketones from adipose cells, sometimes referred to as the “metabolic switch.”14

There are several types of IF diets. Alternate day fasting (ADF) has no calorie intake every other day. Modified ADF (MADF) alternates days of ad lib intake with days of restricting calories to 0% to 40% of usual. TRE allows eating only for a certain part of the day, typically 12 hours or less.14,15

The nutritional adequacy of IF diets hasn’t been comprehensively assessed. Compared with Mediterranean and paleo diets, IF diets are lower in fiber and higher in ultraprocessed foods.16

Data from rodent studies suggest that periods of fasting have associated health benefits, but data from human studies are more limited. Studies of both ADF and MADF have shown potential benefits for weight loss, better glucose control, improved inflammatory markers, and improved lipid profiles, but results generally have been mixed and effects modest.15

The Pegan Diet

The pegan diet is a hybrid diet including aspects of the low-carbohydrate, high-fat paleo diet and the low-fat, higher-carbohydrate vegan diet along with TRE. It capitalizes on the human evolutionary capacity for digesting both plants and meats.9,17 As a hybrid diet, it has some similarities to the Mediterranean diet, and O’Keefe and colleagues have proposed a similar plant-rich diet with seafood as the animal protein source that includes an IF aspect.9,17 Each of the diets has some nutritional strengths that possibly complement one another. For example, including some meat addresses the iron and vitamin B12 shortfalls of the vegan diet. More research is needed on how health impacts are affected by this hybrid diet.

Effect of the Pegan Diet on Body Systems — Principle One

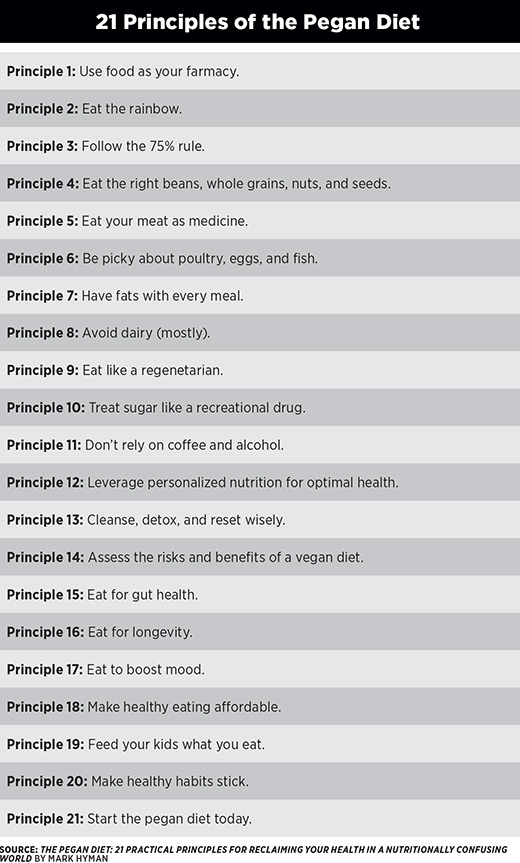

The pegan diet is presented in a series of 21 principles, listed in the table below. The first principle, “use food as your farmacy,” reviews how food impacts the gut microbiome, immune and inflammatory systems, the energy system, the detoxification system, the circulatory system, the communication systems such as hormones and neurotransmitters, and the cell membrane and musculoskeletal structure. Hyman introduces specific foods that are expanded on in the subsequent principles and emphasizes the concept of food as an important determinant of individual biology.18

Key Role of Fruits and Vegetables — Principles Two and Three

Principles two and three, “eat a rainbow” and “follow the 75% rule,” reflect the emphasis on plant foods, especially vegetables, in the pegan diet. Vegetables are nutrient dense and high in fiber and phytonutrients, which Hyman ties to boosted immunity, decreased inflammation, decreased cancer risk, and antiaging potential.19 They also have a low glycemic index to help balance blood sugar.20 Hyman recommends 6 to 8 cups of vegetables daily with 75% of the plate consisting of nonstarchy vegetables.21 The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) recommend 21/2 cups of vegetables and 2 cups of fruit daily.22

The importance of fruits and vegetables for health is borne out by research on vegan diets. The fruits and vegetables in vegan diets are associated with decreased blood cholesterol, stroke incidence and mortality, and mortality from ischemic heart disease.10 The Adventist Health Study (AHS-2), with more than 96,000 participants, showed a 75% risk reduction for hypertension with a vegan diet. AHS-2 and two other large (> 22,000) cohorts found a 26% to 68% decreased mortality risk from ischemic heart disease for vegetarians. Vegan subjects had lower BMI and lower plasma lipids than other vegetarians or omnivores.13

The antioxidant and antiproliferative actions of phytochemicals and the lower BMI associated with vegan diets may decrease the risk of certain related cancers.10 AHS-2 found a modest 8% reduction in overall cancer risk for vegetarian diets, with the greatest reductions in risk being 50% for colon cancer followed by 23% for gastrointestinal tract cancer, and 35% for prostate cancer.13

Beans, Grains, Nuts, and Seeds — Principle Four

Hyman’s fourth principle is “eat the right beans, whole grains, nuts, and seeds.” Hyman describes beans as “carbohydrate heavy” and without significant protein. Lupini beans, green peas, lentils, snow peas, black-eyed peas, and mung beans are recommended as being lower in starch.23 The DGA consider beans, peas, and lentils to have characteristics of both protein and vegetable foods and recommend 1 to 11/2 cups weekly.24

Hyman recommends using dry beans and soaking them because canned beans may absorb the chemicals bisphenol A, S, or F (BPA, BPS, or BPF) from the can lining.23 Blackburn and colleagues demonstrated that BPA levels can be decreased by rinsing canned beans before use.25 Hyman also cites lectins and phytates as possible drawbacks to using beans.23 Petroski and Minnich reviewed the significance of antinutrients and found that usual processing methods, such as boiling or autoclaving, significantly decreased lectin content in beans. No strong evidence was found for a negative effect of lectins on inflammation, intestinal permeability, or nutrient absorption. Phytate levels in grains and beans are decreased with typical preparation methods such as soaking, fermentation, leavening, sprouting/germinating, and cooking. Although phytates have been associated with decreased absorption of zinc and iron, this can be ameliorated with a high vitamin C intake.26

The pegan diet allows only unprocessed gluten-free grains such as brown rice, black rice, teff, amaranth, buckwheat, and quinoa and recommends ½ to 1 cup of whole grains daily.27 Hyman doesn’t recommend gluten because in his view it leads to leaky gut, autoimmune disease, and inflammation. Hyman estimates that 20% of the population has nonceliac gluten sensitivity, although this figure hasn’t been supported by population studies.28,29 Widespread use of gluten-free diets has been contraindicated because of their expense, potential positive effects of gluten on serum triglyceride levels, and nutrient shortfalls, including zinc, iron, magnesium, calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin B12.29 The DGA recommend six nutrient-dense grain servings per day, with half or more as whole grains.30

Pegan Diet Protein and Fat Sources— Principles Five, Six, and Seven

Grass-fed meat, pasture-raised poultry and eggs, and low-mercury fish are the recommended protein sources reviewed in principles five and six.31 Hyman cites the superior nutritional content of grass-fed meat over conventionally raised, including the omega-3 fatty acid content, conjugated linoleic acid, phytochemicals, and increased vitamins and minerals.32 Nogoy and colleagues reviewed studies on the characteristics of grass-fed vs grain-fed beef. They found that the grass-fed meat had a lower total fat and saturated fat content, a more favorable fatty acid profile, more omega-3 fatty acids, and a lower omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acid ratio.33 Studies on pasture-raised eggs have shown that they have comparable amino acid content, more omega-3 fatty acids, and slightly lower, but not always statistically significant, cholesterol levels than eggs from caged hens fed grain-based feed.34,35

Meat is described as a side dish for the pegan diet, with a palm-sized portion of about 4 oz twice daily recommended.36 This exceeds the protein recommendations of the DGA, which suggest about 6 oz daily (39 oz equivalents per week).37 In their pesco-Mediterranean diet, O’Keefe and colleagues emphasize quality protein but caution against excess meat consumption due to increased risk of CVD, diabetes, and gastrointestinal tract cancer.17 Hyman, however, attributes these risks primarily to the effects of sugar and starch on lipoprotein size and composition.38 Other health concerns about meat involve the formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and advanced glycation end products with cooking. These can be partially ameliorated by lower temperature cooking methods and the use of a variety of herbs and spices.39

The pegan diet emphasizes including healthful fats, as noted by principle seven, “have fats with every meal.”40 Recommended fats include avocados, olives, nuts and seeds, extra virgin olive oil, avocado oil, small amounts of butter, grass-fed ghee, coconut oil, and MCT oil.41 Vegetable oils manufactured by heat and solvent extraction aren’t recommended.42 The DGA recommend excluding butter, coconut, palm kernel, and palm oils due to their high saturated fat content.43 The DGA recommend limiting oils to 27 g per day, which is equal to about 2 T.37

Avoiding Dairy and Meeting Vitamin D Needs — Principle Eight

In principle eight, Hyman recommends generally avoiding dairy because of potential increased risk of allergies, eczema, cancer, hormone disorders, autoimmune disease, and digestive problems.44 Willett and Ludwig’s comprehensive review of the role of milk in human health largely supports a limited role for dairy, concluding that zero to two daily servings of dairy are appropriate for adults. They note that milk can be a valuable food for regions with poor overall diet quality and in low-income populations.45 Dairy protein at 14 to 40 g per day has been demonstrated to maintain muscle mass with aging.46 Hyman suggests sheep, goat, or A2 dairy products for those who prefer to include dairy.47 A2 milk differs from A1 milk in that digestion doesn’t produce beta-casomorphin-7, which may be responsible for some of the gastrointestinal symptoms often attributed to lactose intolerance and believed to be the proinflammatory compound in milk.48

Hyman recommends getting adequate dietary calcium from vegetables, sardines, and canned salmon and vitamin D from porcini mushrooms and sunlight exposure.44 Mushrooms that have been exposed to sunlight contain significant amounts of vitamin D and have been found to be as effective as supplements in improving serum vitamin D levels.49 The DGA recommend 3 cups of dairy or the equivalent amount of fortified soy milk daily.37

Regenerative Eating — Principle Nine

Principle nine, “eat like a regenetarian,” advocates using food choices to influence food systems that are compatible with long-term planetary health. Pegan diet food choices are designed to support regenerative agriculture, an approach that emphasizes growing plants and raising animals in ways that revitalize soil, conserve water, and sequester greenhouse gases.50 This contrasts with modern farming approaches that emphasize output, productivity, and profit maximization.51 In general, diets with a higher plant content have a lower negative impact on greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption, soil quality, and water use.12 Hyman also recommends reducing and composting food waste, decreasing use of plastics, shopping locally, choosing organic products, and eating whole foods.52

Sugar, Coffee, and Alcohol — Principles 10 and 11

Principle 10 recommends limiting sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, and artificial sweeteners. Sweeteners allowed in limited amounts include monk fruit, organic whole-leaf stevia, date sugar, honey, maple syrup, coconut sugar, molasses, and small amounts of fresh fruit juice. Hyman labels sugar a “recreational drug,” and states that sugar addiction is a biological disorder. He cites high-fructose corn syrup in soda as the number one cause of fatty liver disease in children and associates it with leaky gut.53 Hyman uses sensational language to describe concerns that are largely advocated by research, although currently there’s no compelling support to call sugar an addictive substance in the physiological sense.54 Sugar, particularly fructose, is implicated in obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and increased gut permeability.55,56 The pegan diet doesn’t recommend artificial sweeteners and sugar alcohols because they “rewire your brain,” are associated with obesity and belly fat, and are “highly addictive.”53 Nonnutritive (artificial) sweeteners have been associated with weight gain, sweet cravings, appetite stimulation, and changes in microbiome composition and glucose metabolism.57,58 The DGA recommend limiting added sugars to less than 10% of calories daily and notes that questions remain about the role of nonnutritive sweeteners in long-term weight control.59

Hyman discourages relying on coffee and alcohol in principle 11, advocating instead for plain filtered water.60 This is supported by the current DGA.61 Hyman says coffee and tea, especially green tea with its phytochemical content, are acceptable for those not adversely affected by caffeine.62 The DGA note that the most nutrient dense choices for coffee and tea have no added sweeteners or cream. There are generally no negative effects from caffeine at intakes up to 400 mg per day.61

The pegan diet limits alcohol to one serving of wine or liquor (no beer) three to four times per week.63 The DGA recommend zero to one serving per day for women and zero to two servings per day for men.64

Personalized Nutrition — Principle 12

In principle 12, Hyman advocates personalized nutrition based on individual and family history and specialized testing, including hormone levels, nutrient assays, stool analysis, food sensitivity testing, and genetic testing.65 To justify nutrient testing, Hyman states, “90% of Americans are deficient in one or more nutrients,” an uncited claim that stands in opposition to the CDC’s Second Nutrition Report, which found the prevalence of deficiencies for any nutrient to be about 10% or less.66 The DGA suggest personalization based on food preferences, cultural foodways, and budgetary resources.67

The 10-Day Reset — Principle 13

Principle 13 suggests that pegan diet adherents cleanse, detox, and reset wisely. His 10-Day Reset is purported to “reboot your biology, reduce cravings, reduce inflammation, optimize your gut health, and support healthy blood sugar.”68 Detoxes and cleanses are popular, and short-term positive results are reported in testimonials, but they haven’t been rigorously studied and typically fail to identify the “toxins” being cleansed or the mechanism of the cleansing.7,69 Despite the principle’s use of popular buzzwords, the 10-Day Reset does contain nutrient-dense whole foods from within the pegan diet principles.68 In addition to the 10-Day Reset, this principle recommends TRE with a 12- to 14-hour window overnight and adequate scheduled sleep.70

Vegan Pegan Option — Principle 14

In principle 14, Hyman discusses the possibility of taking a vegan approach to the pegan diet. He recommends being sure to include tempeh, tofu, lentils, low-starch beans, and gluten-free whole grains.71 Vegan diets have potential nutrition shortfalls (see discussion of the vegan diet) and may not be preventative against sarcopenia with aging.17,72 Gupta and colleagues use the term pegan to refer to a vegetarian pegan diet, which they assessed to be nutritionally unbalanced but possibly appropriate for those who have religious restrictions about eating meat.6

The Healthy Gut — Principle 15

In principle 15, “eat for gut health,” Hyman recommends achieving a healthy gut by eliminating “gut-busters” (grains, gluten, dairy, sugars, refined oils and fats, and some medications), adding beneficial microorganisms with fermented or cultured foods, and supporting the microbiome with prebiotic and fiber-rich foods.73

Both vegan and paleo diets have been associated with benefits to the microbiome. The vegan diet yields a more diverse gut microbiome, helps strengthen the mucosal barrier, yields anti-inflammatory benefits, and potentially plays a role in improving blood lipid profiles, glucose metabolism, body weight regulation, protection against inflammatory bowel disease, and immune function.74 Subjects (n=15) who followed a modern paleo diet showed a far greater microbiota diversity than those on a Mediterranean diet (n=143) after 12 months.75 Fecal analysis of samples from a modern hunter-gatherer population, the Hadza of Tanzania, showed a greater microbial concentration and diversity than samples from Italian urban dwellers.76

Insulin Sensitivity and Longevity — Principle 16

Principle 16, “eat for longevity,” recommends IF approaches, as introduced in principle 13. The goal is to improve glucose metabolism and decrease insulin resistance. Hyman suggests confining intake to a period of 12 hours or less each day. He also suggests a longer fasting period twice weekly and a 24-hour fast monthly.77

The human circadian rhythm, which Hyman introduces in principle 13, may play a role in the efficacy of fasting. This is borne out in studies of shift workers and reflects the decline in insulin sensitivity as the day goes on.15,78

Studies of the pegan diet components have shown a benefit to insulin sensitivity and MetS. IF/TRE has been associated with decreased glucose regulatory markers, reduced fasting insulin, and lower BMI.14,15 The paleo diet has been associated with improved blood pressure, better glucose tolerance, decreased insulin secretion, increased insulin sensitivity, reduced waist circumference, lower body weight, and improved lipid profiles.4,6,79,80 The vegan diet may support improved glucose control and lower risk of MetS because of its moderate calorie content, low glycemic index, and high content of fruits, vegetables, and fiber. In small studies, vegan diets led to favorable glucose control compared with low-fat (n=11) or standard diets for diabetes (n=99).12,81 The AHS-2 (n=>96,000) showed a 47% to 78% reduced risk of type 2 diabetes with a vegan diet.13 Vegan diets also reduce the atherogenic apolipoproteins (ApoB and ApoE) secondary to a high intake of plant sterols and stanols.12

Animal protein is emphasized in principle 16 because of its role in preserving muscle mass.77 O’Keefe and colleagues echo the importance of animal proteins to prevent sarcopenia in their pesco-Mediterranean diet.17 The anabolic response to protein intake is blunted in older adults, and animal proteins that have a complete amino acid profile and are easily digested are most effective for muscle protein synthesis in this age group.82,83 Aerobic and resistance exercise also likely play a role in preventing sarcopenia.83,84

Mood and Food — Principle 17

In principle 17, “eat to boost mood,” Hyman says that whole foods are better for depression.85 He cites omega-3 fatty acids, magnesium, vitamin D, zinc, selenium, and B vitamins as key nutrients for brain health and recommends consuming fatty fish, berries, fiber-rich and fermented foods, green tea, nuts, and seeds.86 These foods are consistent with the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet, which has been associated with delaying age-related declines in cognitive function.87

Mediterranean diets have been associated with improved perceived stress and well-being and decreased risk of depression.88-90 Omega-3 fatty acids are likely beneficial for depression, and there’s suggestive evidence that omega-3 supplementation is a beneficial adjunct to treatment of depression.88 The anti-inflammatory foods in the pegan diet may be helpful. In a study with 15,093 participants, those in the highest quintile for the Dietary Inflammatory Index had a 47% higher risk of future depression than those in the lowest quintile.88,89 Emerging evidence also suggests a role for a healthy microbiome in decreasing risk of depression.89

Affordability of a Pegan Diet — Principle 18

Principle 18 addresses the cost of the pegan diet. Throughout the text, various specialty ingredients such as lupini beans, black rice, and herbs and spices are recommended, and these specialty ingredients may drive up the cost. Less expensive staples such as beans and grains are excluded.

The focus on including meat, particularly grass-fed meat, also increases the cost. For the paleo diet, meat represents 59% of every food dollar spent.91 In the Nogoy review, the price for grass-fed beef was 47% higher by weight than conventionally raised beef.32 Other products that may increase the cost are coconut products and nut milks. For those choosing a paleo diet, the estimated food cost was 26.2% of the average income. This might be a financial barrier, as food costs greater than 25% of disposable income are associated with increased risk of food insecurity.91

The Pegan Diet and Children — Principle 19

Principle 19, “feed your kids what you eat,” urges families to plan meals, shop, and cook together. Hyman suggests that parents feed children what they eat themselves, and that they observe the division of responsibility at meals, which is consistent with the position statement “Nurturing Children’s Healthy Eating.”92,93 Hyman is consistent with the DGA on introducing solids at age 6 months.92,94 The pegan diet guidelines for infants and toddlers differ from the DGA, which recommend introducing cow’s milk at age 12 months and potentially allergenic foods at 6 months, along with other complementary foods.95 The pegan diet recommends delaying all milk, cheese, and dairy until age 2.92 Milk is the major source of energy, protein, fat, and vitamins A, D, B12, and riboflavin in the diets of children aged 12 to 24 months, so careful attention to adequacy is indicated.96 Hyman notes that older children can follow the pegan diet as long as calorie needs are met.92

Building Good Habits — Principle 20

Principle 20 of the pegan diet describes making healthy habits stick by using a three-step process of identifying the “why” behind healthy eating, enlisting the help of friends and family, and starting with small steps.97 These recommendations are consistent with research on habits and behavioral change. Having a motive for maintaining new behaviors and having environmental and social support are among the theoretical themes for health behavior change identified by Kwasniska and colleagues in their review of 100 published theories of behavior change.98 Hyman refers readers to BJ Fogg’s Tiny Habits® approach to incremental behavior change, which uses immediate rewards to help develop consistent and automatic behaviors without relying solely on intrinsic motivation.97,99

Getting Started With the Pegan Diet — Principle 21

Hyman’s final principle, number 21, urges readers to get started immediately. He offers a list of tips including food selection suggestions such as looking for foods in their natural form, foods without labels, foods with no “ingredients you can’t pronounce,” and foods with no GMOs.100 He suggests shopping the periphery of the store, which is advice that’s consistent with that of other healthful eating guidance.100,101 He identifies superfoods as berries, green tea, wild salmon, anchovies, grass-fed meat, goat’s milk yogurt, broccoli, black rice, and leafy greens.102 The superfood concept has been criticized as being poorly defined and decreasing dietary variety.103

To help readers implement the pegan diet, there’s a concluding section with recipes and cooking suggestions. The recipes tend to be time-consuming, including steps like soaking beans or grinding ingredients, and they have long ingredient lists. However, there’s helpful advice on learning how to cook flavorful vegetables by steaming, sautéing, or roasting.104

Putting It All Together

The pegan diet is an attempt to integrate complex concepts of healthful whole foods, sustainable agriculture, responsible consumer choices, and the social value of meals. It hasn’t been researched, so evaluation comes from looking at research on its component paleo, vegan, and TRE diets.

It’s unknown whether consumers will find the pegan diet sustainable. For the paleo diet, Jospe and colleagues found a high attrition rate (only 16 of 46 participants maintained the diet for 12 months), with most participants continuing to include grain products and sugars or sweets at least once weekly.16 Basile surveyed paleo diet adherents and found 70% rated the diet easy to follow. Barriers included social pressures, limited food choices, time constraints, difficulty eating away from home, and expense.105 Vegan diets generally are well-accepted, with potential barriers cited as sensory enjoyment of animal products, inconvenience of preparation, and expense.106-108 RDs should consider screening clients interested in the pegan diet for disordered eating, as a focus on healthful foods may be associated with an increased risk of pathological anxiety about food quality, such as seen in orthorexia.109

The pegan diet’s strengths include its plant-rich emphasis and the use of whole, less-processed foods. Concerning aspects include the elimination or limitation of major food groups such as grains, legumes, and dairy and the lack of research on its efficacy. Health professionals can assist those who want to follow the diet with finding lower cost, culturally appropriate foods and assuring adequate intakes of calcium and vitamin D.91

— Kathleen Searles, MS, RDN, LD, is a nutrition consultant in private practice.

Learning Objectives

After completing this continuing education course, nutrition professionals should be better able to:

1. Assess the strengths of the pegan diet approach.

2. Evaluate the weaknesses of the pegan diet approach.

3. Assist clients in planning nutritionally complete meals using the pegan diet approach.

4. Counsel clients on the environmental and ethical considerations of the pegan diet.

Examination

1. Which of the following is the best definition of the pegan diet?

a. A semivegetarian form of the Mediterranean diet

b. A plant-rich, whole foods, hybrid diet to lower incidence of chronic disease

c. A low-carbohydrate diet for short-term use for weight loss

d. A gluten-free approach designed to manage celiac disease

2. Which of the following would be a good reason for choosing the pegan diet?

a. Plant-rich emphasis and use of whole, less-processed foods

b. Use of specialty ingredients such as mung beans and wild rice

c. Ethical concerns about consuming animal foods

d. Ease of preparation

3. Factor(s) that may increase the cost of implementing the pegan diet include which of the following?

a. Elimination of most grains, beans, and dairy

b. Buying gluten-free specialty products

c. Purchasing a large amount of vegetables

d. Price of grass-fed meat vs conventionally raised meat

4. What would be a good way to meet vitamin D needs with the pegan diet?

a. Mushrooms that have been exposed to sunlight

b. It isn’t possible; a vitamin D supplement is necessary.

c. A daily serving of goat’s milk yogurt

d. Using raw A2 milk

5. Which of the following best describes regenerative agriculture?

a. Emphasis on output, productivity, and profit maximization

b. Plant-based agriculture with no animal husbandry

c. Emphasis on methods that revitalize soil, conserve water, and sequester greenhouse gases

d. Cultivation with traditional hunter-gatherer methods

6. What pegan diet–friendly protein sources can dietitians recommend for clients who want to try the pegan diet but don’t eat meat?

a. Soy burgers, canned beans, milk, and yogurt

b. Pasture-raised eggs, tempeh or tofu, and low-starch beans

c. Cheese, eggs, and fish

d. It isn’t possible to eat a pegan diet without meat.

7. What part of the pegan diet is most likely to contribute to overall health?

a. Avoiding lectins and phytates

b. Limiting alcohol to three to four times per week

c. Avoiding grains that contain gluten

d. Eating 6 to 8 cups of vegetables daily

8. Which best describes time-restricted eating in the pegan diet?

a. Consuming foods during a period less than or equal to 12 hours each day

b. Eating meals and snacks at a set time each day

c. Alternating days of very low-calorie intake with days of ad lib intake

d. Following the 10-day reset

9. Which of the following is a way the pegan diet agrees with the 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans?

a. Avoiding potential food allergens until age 2 or older

b. Using a variety of fats, including coconut oil and MCT oil

c. Limiting added sugars

d. Avoiding most dairy for adults

10. What is a valid reason to recommend the pegan diet to a client?

a. Ninety percent of Americans have deficiencies in one or more nutrients.

b. The client has celiac disease and is seeking a whole foods diet.

c. The client has a limited food budget and wants to focus on the most healthful foods.

d. The client usually eats away from home but wants the most healthful choices.

References

1. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:3-5.

2. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:8-9.

3. Bland J. Defining function in the functional medicine model. Integr Med. 2017;16(1):22-25.

4. Jamka M, Kulzynski B, Juruć A, Gramza-Michalowska, Stokes CS, Walkowiak J. The effect of the paleolithic diet vs. healthy diets on glucose and insulin homeostasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Med. 2020;9:296.

5. Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, et al. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;80:341-354.

6. Gupta L, Khandelwal D, Lal PR, Kaira S, Dutta D. Palaeolithic diet in diabesity and endocrinopathies — a vegan’s perspective. Eur Endocrinol. 2019;15(2):77-82.

7. Tahreem A, Rakha A, Rabail R, et al. Fad diets: facts and fiction. Front Nutr. 2022;9:960922.

8. Tarantino G, Citro V, Finelli C. Hype or reality: should patients with metabolic syndrome-related NAFLD be on the hunger-gatherer (Paleo) diet to decrease morbidity? J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015;24(3):359-368.

9. Bland JS. Why the pegan diet makes sense. Integr Med. 2021;20(2):16-19.

10. Craig WJ. Health effects of vegan diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1627S-1633S.

11. Definition of veganism. The Vegan Society website. http://vegansociety.com/go-vegan/definition-veganism. Accessed December 27, 2022.

12. Marrone G, Buerriero C, Palazetti D, et al. Vegan diet health benefits in metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. 2021;13(3):817.

13. Le LT, Sabaté. Beyond meatless, the health effects of vegan diets: findings from the Adventist cohorts. Nutrients. 2014;6(6):2131-2147.

14. Patikorn C, Roubal K, Veettil SK, et al. Intermittent fasting and obesity-related health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2139558.

15. Patterson RE, Sears DD. Metabolic effects of intermittent fasting. Annu Rev Nutr. 2017;37:371-393.

16. Jospe MR, Roy M, Brown RC, et al. Intermittent fasting, Paleolithic, or Mediterranean diets in the real world: exploratory secondary analyses of a weight-loss trial that included choice of diet and exercise. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111(3):503-514.

17. O’Keefe JH, Tores-Acosta N, O’Keefe EL, et al. A pesco-Mediterranean diet with intermittent fasting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(12):1484-1493.

18. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:17-30.

19. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:31-32.

20. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:37.

21. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:33,37.

22. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, p. 33. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

23. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:42-46.

24. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, pp. 20,31. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

25. Blackburn BE, Cox KJ, Zhang U, Anderson DJ, Wilkins DG, Porucznik CA. Effect of rinsing canned foods on bisphenol-A exposure: the hummus experiment. Experimental Results. 2020;1(e45):1-10.

26. Petroski W, Minnich DM. Is there such a thing as “anti-nutrients”? A narrative review of perceived problematic plant compounds. Nutrients. 2020;12:2929.

27. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:48,50.

28. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:47.

29. Roszkowska A, Pawlicka M, Mroczek A, Balabuszek K, Nieradko-Iwanicka B. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: a review. Medicina. 2019;55:222.

30. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, pp. 20,32. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

31. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:60,67,81.

32. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:58

33. Nogoy KM, Sun B, Shin S. Fatty acid composition of grain and grass-fed beef and their nutritional value and health implication. Food Sci Anim Resour. 2022;42(1):18-33.

34. English MM. The chemical composition of free-range and conventionally-farmed eggs available to Canadians in rural Nova Scotia. PeerJ. 2021;9:e11357.

35. Anderson KE. Comparison of fatty acid, cholesterol, and vitamin A and E composition in eggs from hens housed in conventional cage and range production facilities. Poult Sci. 2011;90:1600-1608.

36. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:60,67.

37. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, p. 20. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

38. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:57-60.

39. Provenza FD, Kronberg SL, Gregorini P. Is grass-fed meat and dairy better for human and environmental health? Front Nutr. 2019;6:26.

40. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:68.

41. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:73.

42. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:70

43. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, pp. 35,44. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

44. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:75

45. Willett WC, Ludwig DS. Milk and health. N Eng J Med. 2020;382:644-654.

46. Hanach N, JcCullough F, Avery A. The impact of dairy protein on muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance in middle-aged to older adults with or without existing sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:59-69.

47. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:78.

48. Kay SS, Delgadoo S, Mittal J, Eshraghi RS, Mittal R, Eshraghi AA. Beneficial effects of milk having A2 β-casein protein: myth or reality? J Nutr. 2021;151(5):1061-1072.

49. Cardwell G, Bornma JF, James AP, Black LJ. A review of mushrooms as a potential source of dietary vitamin D. Nutrients. 2018;10(10):1498.

50. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:81.

51. Gordon E, Davilla F, Riedy C. Transforming landscapes and mindscapes through regenerative agriculture. Agric Human Values. 2022;39:809-826.

52. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:83-85.

53. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:87-91.

54. Westwater ML, Fletcher PC, Ziauddeen H. Sugar addiction: the state of the science. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55:S55-S69.

55. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, p. 103. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

56. Jensen T, Abdelmalek MF, Sullivan S, et al. Fructose and sugar: a major mediator of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;68(5):1063-1075.

57. Suez J, Korem T, Zilbema-Schapira G, Segal E, Elinav E. Non-caloric artificial sweeteners and the microbiome: findings and challenges. Gut Microbes. 2015;6(2):149-155.

58. Gardener HE, Elkind MSV. Artificial sweeteners, real risk. Stroke. 2019;50(3):549-551.

59. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, pp. 41,103. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

60. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:92, 96.

61. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, p. 35. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

62. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:96.

63. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:94.

64. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, p.104. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

65. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:98-100.

66. Pfeiffer CM, Sternberg MR, Schleicher RL, Haynes BMH, Rybak ME, Pirkle JL. CDC’s second national report on biochemical indicators of diet and nutrition in the US population. J Nutr. 2013;143(6):938S-947S.

67. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, p. 27. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

68. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:105-106.

69. “Detoxes and “cleanses”: what you need to know. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health website. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/detoxes-and-cleanses-what-you-need-to-know. Updated September 2019. Accessed January 26, 2023.

70. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:113.

71. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:117

72. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:115

73. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:123-125.

74. Sakkas H, Bozidis P, Touzios C, et al. Nutritional status and the influence of the vegan diet on the gut microbiota and human health. Medicina. 2020;56(2):88.

75. Barone M, Turroni S, Rampelli S, et al. Gut microbiome response to a modern Paleolithic diet in a Western lifestyle context. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0220619.

76. Zopf Y, Reljic D, Dieterich W. Dietary effects on microbiota—new trends with gluten-free or paleo diet. Med Sci. 2018;6(4):92.

77. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:131-135.

78. Dong TA, Sandesara PB, Shindsa DS, et al. Intermittent fasting: a heart healthy dietary pattern? Am J Med. 2020;133(8):901-907.

79. Otten J, Stomby A, Waling M, et al. Effects of a Paleolithic diet with and without supervised exerciseon fat mass, insulin sensitivity and glycemic control: a randomized controlled trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33(1):10.1002/dmrr.2828.

80. Mannheimer EW, vanZuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Pijl H. Paleolithic nutrition for metabolic syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:922-932.

81. Barnard HD, Cohen J, Jenkins DJA, et al. A low-fat vegan diet improves glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in a randomized clinical trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(8):1777-1783.

82. Berrazaga I, Micard V, Gueugneau M, Walrand S. The role of the anabolic properties of plant- versus animal-based protein sources in supporting muscle mass maintenance: a critical review. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1825.

83. Makanae Y, Fujita S. Role of exercise and nutrition in prevention of sarcopenia. J Nutri Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2015;61:S125-S127.

84. Vikberg S, Sorlen N, Branden L, et al. Effects of resistance training on functional strength and muscle mass in 70-year-old individuals with pre-sarcopenia: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(1):28-34.

85. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:137.

86. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:140-141.

87. Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, et al. MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(9):1015-1022.

88. Bremner JD, Moazzami K, Wittbrodt MT, et al. Diet, stress, and mental health. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2428.

89. Firth J, Gangwisch JE, Borsini A, Watson RE, Mayer EA. Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental well-being? Br Med J. 2020;369:m2382.

90. Quirk SE, Williams LJ, O’Neil A, et al. The association between diet quality, dietary patterns and depression in adults: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:175.

91. Bracci EL, Milte R, Keogh JB, Murphy KJ. Developing and implementing a new methodology to test the affordability of currently popular weight loss diet meal plans and healthy eating principles. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:23.

92. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:150-154.

93. Haines J, Haycroft E, Lytle L, et al. Nurturing children’s healthy eating: a position statement. Appetite. 2019;137:124-133.

94. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, p. 60. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

95. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025, p. 58. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. Accessed December 30, 2022.

96. Fox MK, Reidy K, Novack T, Ziegler P. Sources of energy and nutrients in the diets of infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(1 Suppl 1):S28-42.

97. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:156-160.

98. Kwasniscka D, Dombrowski SI, White M, Sniehotta F. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: a systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(3):277-296.

99. Hollingsworth JC, Young KC, Abdullah SF, et al. Protocol for minute calisthenics: a randomized controlled study of a daily, habit-based, body weight resistance training program. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1242.

100. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:161-163.

101. 9 grocery shopping tips. American Heart Association website. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/cooking-skills/shopping/grocery-shopping-tips. Updated April 16, 2018. Accessed January 27, 2023.

102. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:165.

103. Superfoods or superhype? Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health website. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/superfoods/. Accessed January 27,2023.

104. Hyman M. The Pegan Diet: 21 Practical Principles for Reclaiming Your Health in a Nutritionally Confusing World. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark; 2021:173-174.

105. Basile AJ, Schwarts DB, Stapell HM. Paleo then and now: a five-year follow-up survey of the Ancestral Health community. Journal of Evolution and Health. 2020;5(1). https://doi.org/10.15310/J35147502.

106. Barnard ND, Gloede L, Cohen J, et al. A low-fat vegan diet elicits greater macronutrient changes, but is comparable in adherence and acceptability, compared with a more conventional diabetes diet among individuals with type 2 diabetes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2):263-272.

107. Bryant CJ. We can’t keep meating like this: attitudes towards vegetarian and vegan diets in the United Kingdom. Sustainability. 2019;11:6844.

108. Alcorta A, Porta A, Tarrega A, Alvarez MD, Vaquero MP. Foods for plant-based diets: challenges and innovations. Foods. 2021;10(2):293.

109. Gortat M, Samadakiewicz M, Perzyński A. Orthorexia nervosa — a distorted approach to healthy eating. Psychiatr Pol. 2021;55(2):421-433.