Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 17 No. 9 P. 62

Suggested CDR Learning Codes: 6010, 6020, 6050, 6060

Suggested CDR Performance Indicators: 9.2.1, 9.2.3, 9.2.4, 9.4.8

CPE Level 1

Take this course and earn 2 CEUs on our Continuing Education Learning Library

Assessment is a familiar topic in dietetics. RDs perform nutrition assessments of hospital inpatients, outpatients, and private clients. Nutrition assessments are based on numeric data and often include the evaluation of anthropometric data, lab results, clinical findings, food records, and intake/output data. When the assessments are completed, the RD has a useful picture of the patients’ status.

A less familiar but equally important topic is assessment of nutrition education. In education, the term “assessment” includes a broad range of processes for gathering and evaluating information about student learning and the effectiveness of teaching. Some examples include paper-and-pencil tests, performance and project ratings, and direct observations.1 Their purpose is to provide answers to the following questions: Did the learner understand what was taught? Does the learner have a new nutrition life skill? Can the learner use this nutrition information to make personal dietary choices? How can this information be assessed? Are the assessments purely subjective or can there be accurate objective data?

Classroom teaching practices are useful resources for RDs who may need to teach patients in classrooms. In this setting, the patients become the students. Assessment of learning gains is vital to evaluating the success of a classroom experience for any learner. Assessments have the power not only to analyze the teaching but also to be part of it. Well-constructed assessment tools can help the instructor measure the learning gains of the students. In addition, they can help teach and further reinforce the concepts being taught to the students. Good assessments serve both purposes. Assessment data can help RDs plan, refine, and pace lessons. These crucial data are as integral to teaching as nutrition assessments are to dietetics practice.

Initially, assessment of the individuals in a classroom can help the teacher determine the scope and depth of the material to be taught. This involves assessing students’ prior knowledge (an aspect addressed in depth in the first course in this series in the August issue of Today’s Dietitian). An assessment can reveal whether the class members are ready to learn at the same level or if they will need to be divided into different levels of teaching groups and what those levels might be. Also, the dietitian can collect and later use preliminary data to evaluate the progress students have made during class.

There are ways to develop evaluation questions or documents that can impart or reinforce information and enhance students’ skill-building abilities. Assessments are especially powerful when they fulfill the dual purpose of being both evaluation instruments and teaching tools.

Assessments can provide feedback not only to the learner, but also to the nutrition educator. A well-examined class, from the RD’s perspective, can be continually improved. Collected assessment data also can serve as evidence, should any be required, of the effectiveness of a nutrition education program. This can help demonstrate the RD’s cost-effectiveness, the educational benefit to the learner, and, for budgeting purposes, a justification for the RD’s time required.

This continuing education course, the second in a three-part series, explores the different types of learning assessments and the rationale for using them. It presents assessment tools and practical suggestions for how to use them in the health care classroom.

Types of Assessments

As with any science, assessment has its own nomenclature to describe its various aspects. The major types of assessments are formal, informal, formative, and summative. Formal and informal describe the kind of assessment made; formative and summative describe when the assessment is made. Combinations of these are formal formative, formal summative, informal formative, and informal summative. Those combined phrases help teachers accurately communicate with one another (and with administrators) to describe the assessments they perform.

Formal Assessments

A formal assessment is one that students will recognize as an evaluation or assessment; it even may be announced. Often written, these are formalized quizzes, exams, tests, and assignments that instructors can use to determine learning gains.

The assessment will be the same for each student in the class, although teachers can make modifications as needed to accommodate individual participants. These assessments include multiple choice, true or false, short answer, essay, or any other styles of written or recorded testing instruments. Formal oral assessments are based on a predetermined set of interview questions or predetermined criteria for a student presentation. They’re made verbally, but aren’t arbitrary; any formal assessment, written or verbal, has been preplanned and carefully developed.

A pre- and postclass formal assessment may involve using the same assessment tool before the class and again after the course material is presented and learned. These assessments are most useful for determining learning gains.

The term “formal assessment” isn’t interchangeable with “standardized assessment.” “Standardized” means the instructor uses the same assessment instrument for all classes taking the course. While a standardized assessment is most often formal, a formal assessment isn’t necessarily standardized. A teacher could create a different formal assessment for each class of students, which would then not be standardized. In addition, a “standardized test” isn’t necessarily related to teaching done to a “standard.” A teaching standard is used in lesson planning, a topic that will be addressed in the final course in this series. “Standard” and “standardized,” in this case, aren’t synonymous. Educational nomenclature has evolved over time, and even in research writings it sometimes can be confusing.

However, in order to delve deeper into education topics, it’s important to understand the terms. A formal assessment is a planned and usually announced evaluation.

Informal Assessments

Teachers make informal assessments every time they observe, evaluate, or individually note a student. They can make these types of assessments before teaching (by meeting a participant or glancing through a medical chart note), and during and after a teaching experience. These assessments can be useful when teaching has been completed in situations requiring no formal assessment data or feedback.

Informal assessments aren’t limited to in-class experiences; teachers can make them any time they encounter students. While serving as classroom teachers, RDs also may encounter students in a clinical setting. RDs can assess learning gains informally as part of the conversation or interview outside the classroom. And RDs can tailor informal assessments for individual class participants and their ability levels, rather than give the same instrument to various students. For example, for learners with limited English skills, RDs can ask questions in the learners’ native language or communicate with illustrations rather than written words. Dietitians also can ask students what they recalled from the class and listen to the responses.

Formative Assessments

Not to be confused with “formal,” “formative” relates to the meaning of the word “formation.” Formative assessments help the teacher gauge how students are grasping the concepts throughout the learning experience. Formative assessments may be either formal or informal, and usually are performed during the class. A formative assessment is part of a process that occurs during the teaching time, the goal of which is to identify the gap between the students’ current knowledge level and the learning goal level intended for them to reach. It also can refer to the rate at which they’re reaching it.2 Education expert Robert Marzano states that the frequency of formative assessments is related to student academic achievement—the more feedback and assessments the better.3 In other words, they help the instructor answer the questions, “How are they doing? Are they getting this? Should I move on, or should I reteach a concept?”

Formative assessments allow teachers to determine how much students are learning along the way and be certain they understand the last point before moving on. A formative assessment might be a formal written quiz at a midpoint or could be as informal as observation of the learners’ facial expressions as they listen, which could display engagement, boredom, confusion, or frustration. A formative assessment is a method of paying attention to how well it’s going.

Summative Assessments

Upon completion of the learning experience, teachers use summative assessments to measure (sum up) the total learning. These assessments, which are often formal, measure the total accumulation of learning in the class. They also serve as a source of data and feedback for the instructor to help refine the lesson plan or even help defend the departmental teaching budget. An excellent use of a summative assessment would be to compare pre- and postclass test results using the same test.

With this method, it’s possible to quantify learning gains and see the progress made by learners. This same example was used to describe formal assessments, as this assessment is formal. This is a “summative formal assessment.” For example, in a class of learners who need to lose weight, a written pretest might pose questions to assess their understanding of effective weight management strategies. After the class, the instructor could give the same test to the same learners, demonstrating the level of their comprehension of the subject.

Using Assessments in the Health Care Classroom

There are many ways RDs can use assessments in the classroom. An RD presenting a class on lactose intolerance, for example, can conduct an informal formative assessment while teaching. After presenting and discussing lactose fermentation and dairy products, the RD can ask the class members to call out various fermented dairy products. The RD can write correct responses on the board (yogurt, buttermilk, acidophilus milk, etc), while gently correcting wrong answers (chocolate milk, ice cream, soy milk) and not writing these on the board. This is an informal way to assess how students are learning in the formative stages of the lesson. Plus, the list of correct responses visually reinforces the lesson for the learners. In addition, by silently noting which class members provided correct answers and which gave wrong answers, the teacher can informally assess the individual class members’ grasp of the concept during class.

The RD can give a written pretest (a formal formative assessment) to all learners upon referral to a class. And the teacher can collect and score the tests before teaching the class. Using the data from the pretest, the RD can teach the material with greater emphasis on the areas in which many class participants are weak. The RD can give the same test to the class members after the class as a formal summative assessment to clearly measure the learning gains of the class.

Well-designed assessments take time; this is especially true of formal assessments. They must be constructed, administered, returned, and evaluated. Adequate time should be budgeted for these tasks. Expect to spend at least one hour to construct a good assessment instrument from previously established goals and objectives. Allow at least another hour to fully evaluate and comprehend the results of a classroom assessment, perhaps even longer for a class with more than 15 students.

Without adequate time for evaluation and reflection, it’s difficult to fully appreciate whether or not the class was successful and useful to the participants.

Constructing Assessments

RDs are academically successful individuals. Dietetics training is a long road through college and internship and, often, graduate school. The fact that RDs pass a rigorous registration exam after they complete training may demonstrate academic strength, but it also may be a limitation. For example, the quiz/exam approach that’s common in college science courses may be the most familiar assessment tool in academics, but it may not be the most effective tool to assess class participants in a health care setting. The goal in the health care classroom is not to assign grades, but to improve lives. The assessments should actually strengthen the education process by reinforcing the new information and ideas in a positive way. The RD can adapt well-written assessment test items to assess higher levels of thinking, not just the memorization of facts. Then these assessments can enhance the learning process.

For example, in a class about lactose intolerance, the RD can write a test question such as the following:

Dairy foods that have been cultured with bacteria may be better tolerated by a lactose-intolerant person, and would include:

a. Fresh goat’s milk

b. Buttermilk

c. Ice cream

Learners have just read the statement “Dairy foods that have been cultured with bacteria may be better tolerated by a lactose-intolerant person.” Hopefully they were learning and will understand that “buttermilk” is the only cultured option on the list, but even if they weren’t, correct information was reinforced in the assessment.

One of the limitations of written exams is that they may arouse negative emotions in some individuals. Learners can become nervous, anxious, or competitive when they start testing. Test anxiety works against the end goal of learning, so assessments should be straightforward, supportive, and positive experiences. Some students will be open to learning and considering new material until they see a paper test. At that point, learning stops as anxiety begins. When assessments are presented as paper-and-pencil tests, students tend to interpret them as being separate from the curriculum rather than part of it.

Assessments should be designed as learning events rather than examinations that are solely for the advantage of the teachers or researchers.4 Each question should be written in a positive way, with correct statements, such as the buttermilk example above. Written exams should provide opportunities for students to demonstrate what they know, rather than just what they don’t know or are confused by. Trick questions, ambiguity, and vagueness serve no purpose. The best way to find out what the students understand is to allow them to write a little bit, explaining their grasp of a concept. While it might be too much to grade essays in a health care setting, a short written or spoken sentence or two can allow students to share what they know. Every assessment instrument should teach and reinforce the learning experience.

Constructing assessments should be a careful operation. A written test/exam/quiz is called an assessment or an “instrument.” The problems are called items rather than questions. Each item can be a teaching opportunity and therefore deserves careful attention.5 The following principles apply to item writing, whether the items are multiple choice, matching, short answer, or true/false:

• Use positive rather than negative language. For example, rephrasing our buttermilk item above to be negative might read, “A lactose-intolerant person cannot have which of the following: a. Ice cream; b. Buttermilk; c. Cheese.” It’s better to make it positive, such as, “A lactose-intolerant person may tolerate: a. Ice cream; b. Skim milk; c. Cheese.”

• Do not make distractors (incorrect options) that are partly correct or nearly correct. Again, using our buttermilk question, “Dairy foods that have been cultured with bacteria can be better tolerated by a lactose-intolerant person, and would include: a. Cottage cheese; b. Buttermilk; c. Ice cream.” Cottage cheese can be made with both cheese and fresh milk or cream. While this should be addressed in class, it’s a confusing distractor in the assessment item. Keep it precise, not tricky.

• Make sure that the correct choice and the distractors are about the same length.

• Have only one clearly correct answer.

The following is an example of a poor multiple-choice item:

When trying to avoid a high-sodium intake, it’s best not to:

a. Use the salt shaker

b. Use canned soups that contain more than 500 mg of sodium per cup

c. Eat fresh fruits and vegetables

d. A and B

e. A and C

There are several problems with this item. The approach is negative rather than positive in that it asks what one should not do, rather than what one should do. Option B is much longer than the other choices. Options A, B, and D all could be correct. Also, the goal of a low-sodium intake is to limit total sodium over the course of a day, so A and B might not be correct if the entire day’s sodium intake is taken into account. Option C doesn’t specify whether these fresh fruits and vegetables are salted or otherwise seasoned or not. Options D and E aren’t really distractors at all, because they don’t present new information; they simply add to the confusion. It’s possible to choose item E and be partially correct, since A is mentioned in the item, and is actually a correct response. A partially correct answer shouldn’t be marked “wrong” or the student might mentally toss out the correct information along with the incorrect. Plus, the act of reading and figuring out distractors D and E wastes learning time. The student will spend precious learning time just trying to figure it out. This item won’t teach as it assesses.

The following is a better example:

A good strategy for limiting daily sodium intake to 2,000 mg/day would be to:

a. Eat mostly canned foods throughout the day

b. Eat mostly frozen foods throughout the day

c. Keep a running total of sodium intake

d. Restrict the diet to protein foods only

The options are all stated positively rather than negatively. The options are roughly the same length. The distractors are clearly wrong, and there’s only one correct option, which teaches a principle. It may not be easy for a learner to keep a running total of sodium intake throughout the day, but it’s a very good strategy if a learner is serious about following a 2,000 mg/day sodium intake. This concept is reinforced when the learner answers the question. While the correct and incorrect answers seem very obvious to the RD, and to anyone with an understanding of the topic, the goal is to have the assessment item reinforce the learning of correct information. The learners have just read a clear statement about keeping a running total. If they leave the class with that bit of information, they will have made a learning gain they can apply to their daily lives.

Learning Experiences That Assess

After considering assessments that teach and reinforce the learning, it’s time to look at the flip side: learning experiences the RD can use to assess. It’s possible to provide either formal or informal learning experiences that also serve as both formative and summative assessment tools. These are valuable to everyone because they help learners to inquire and search, while at the same time help the teacher gauge student progress and identify problems.

A simple question-and-answer period is an example of an informal formative assessment that can give many clues about class members. They can ask general or specific questions—whichever best fits into the lesson plan—on a certain topic. The teacher can ask questions, too; perhaps the students have answers or hints they can share. An example of a question for the learners might be, “Do any of you have suggestions on how to gather family members for a meal?” The question itself emphasizes the principle of family dining, and class members may have insightful ideas. The teacher can pose a direct question to a quiet class member to help assess that individual’s learning, or can ask for hands. It’s important to allow adequate time for the learners to process the question and develop answers before they speak.

Class presentations by students are formal assessments that can be formative or summative. RDs can provide guidance about research resources so learners, alone or in teams, can create research-based presentations. Among these resources are lists of websites, journals, consumer magazines, and books with reliable nutrition information (such as www.eatright.org) that they can use to research a topic. This not only helps the learners to complete the assignments, it also gives them resources for finding information in the future. Another approach is for the instructor to provide specific information resources for the learners to use in class to answer questions or prepare presentations, such as printed articles, handouts, or books. This allows the RD to control the information sources presented to the students. As students read and prepare, then speak and share their information, they learn on a higher level than they would if they were just to listen to a more typical lecture-style delivery of information. The instructor can assess the level of learners’ understanding while supervising and assisting them with their preparations (informal formative), and again during their presentations (formal formative if it’s at a midpoint of the class, or formal summative if it’s the culminating activity of the class). Throughout the experience, the RD can give timely and positively corrective feedback.6

Both throughout the course (formative) and at the end (summative), dietitians can invite the students to assess themselves. The feedback they provide to the RD and to themselves can be enlightening. The students require time to reflect. Provide time for them to formulate verbal responses or prepare written reflections.6 The goal is for the learners to internalize the information to effect lifestyle change. For example, a breast-feeding class for expectant mothers may begin with a moment to write a reflection on the reasons the mother wants to breast-feed. Later, the mother can reflect on the various challenges that could interfere with breast-feeding and how to overcome them. Finally, the mothers can reflect on the benefits of breast-feeding that they learned about in the class. The more the learners see the material connecting to their real lives, the more responsibility they will take to learn it and the better equipped they will be to make positive changes beyond the classroom.

Assessing the Instruction and the Instructor

To paraphrase an old saying, “If it stops getting better, it stops being good.” Since their goal is to provide the best care possible for their patients, RDs can use assessments to evaluate their teaching for necessary improvement. The success of a class isn’t all about the learners; it’s also about the teacher. Because a course is never static, it always can be a little better next time. It’s worthwhile to take time to fully analyze and evaluate the assessments. There’s often some refinement that can improve the experience for the next group of learners.

At the end of the class, direct student feedback provides assessment of the instructor. For example, the instructor can ask learners how they liked the class, the teacher, the subject, the information, the room, the time, and the rate of delivery.

The RD can ask students to tell or write what they learned; this, in itself, will reinforce their learning. The RD then can ask them what they wanted to learn, but didn’t; this can guide his or her future investigations and lesson plans. This assessment can be anonymous, as the answers may be more honest if the students don’t have to provide their names. This information will help identify problems in the classroom and also may provide some emotional release for the learner. The instructor may need to be thick-skinned to take criticism in stride, then consider and learn from it. Often, the comments are positive and help build both the instructor’s self-esteem and the curriculum for future classes.

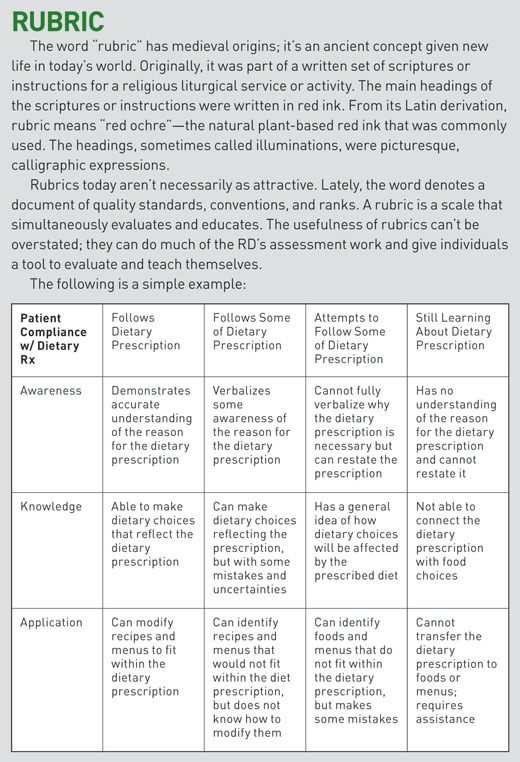

The Rubric

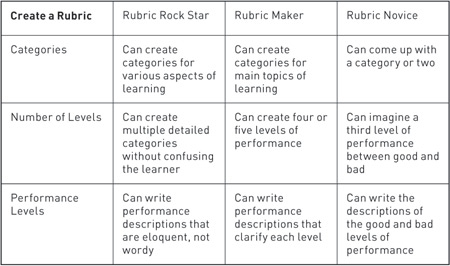

A rubric is an assessment tool that teaches as it evaluates and therefore is useful for both the instructor and the learner.3,7 It looks like a table, but is a much more powerful tool. A rubric is a scale that compares performance against a standard in one or more categories. Students not only learn the principles or ideals, but also where they stand in relation to the ideal performance. They can see how far they need to go and what they need to do to improve.

Creating a rubric requires time and a clear understanding of the goals and purposes of the class as well as the population and culture of the learners. Writing an excellent rubric is an art and a science—a valuable skill that requires practice to develop and refine.

Learners benefit greatly from a rubric they can take home and use. They can take ownership of their performance level and motivate themselves to improve or not—it’s their decision. It puts the ball in their court, while still giving the RD an assessment instrument.

As an exercise, the RD can create a rubric for any area of teaching or practice.

Writing a rubric is a step-by-step process, as follows:

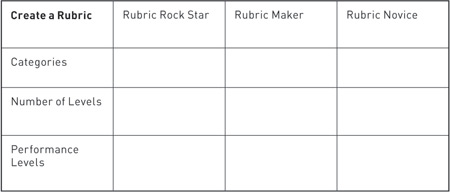

1. Identify an area that could be described in a rubric, and give it a name. This one is called “Create a Rubric.”

2. Establish categories of performance. What do the learners need to know or do? These are the categories that would be placed down the outside left column of the rubric when presented in table form.

For this exercise, use the development of the rubric itself as the source of the categories. Therefore, the first category is called “categories.” Other aspects of rubric writing include “number of levels” and “performance levels,” so use each of these as a category as well, placing them down the left side. No matter what topic you’re addressing in a rubric, there will be a few definable categories that help describe the process of learning the topic.

3. Determine the number of performance levels between highest and lowest performance. These levels of quality are listed across the top of the rubric, with the highest or best performance on the inside left column, closest to the categories. The lowest performance should be the column farthest to the right of the ideal. Do not include a “no effort” or “failure” column in a health care setting, where student performance isn’t a matter of grading.

It’s now possible to visualize what these categories and performance levels mean. In each category down the left side, the performance will be evaluated and ranked by the different descriptors across the top.

4. Describe the levels of performance. Each level needs to be clearly described so that learners can assess their performance levels. Use positive language to describe each level, even the lowest.

The teacher should keep in mind that most of the students will be at the novice level of any nutrition skill that’s taught in the class, and many will be unaccustomed to using rubrics, especially if it has been a few years since they were in high school. It might be a good idea to explain a rubric that’s used in class so all the learners understand how to use it.

Putting It Into Practice

Assessment is an integral part of the teaching and learning experience that allows the instructor to glean information that informs future teaching. Assessments also allow the RD to gather data about the effectiveness of education programs. These data can be used in a variety of practical ways, such as to bolster classroom budgets, defend insurance reimbursement for classes, and enter learning gains directly into a learner’s medical chart. Assessment skills allow the RD to quantify and communicate these data. In addition, well-designed assessments can help the participant learn even more about the subject. Assessments can be memorable and motivating over the long term so learning will continue beyond the classroom and will include building blocks of understanding gathered from various life and classroom experiences.8

Effective learning experiences, rubrics, and assessment instruments can help provide these building blocks for continued learning. With practice, RDs can build assessment strategies into their teaching strategies in nutrition education classrooms in the health care setting.

— Kristine M. Westover, MS, RDN, LDN, is a high school teacher and author who lives and works in Oregon. A graduate of Brigham Young University and Western Oregon University, she’s the co-owner of Four Score Media, which creates teaching tools and textbooks.

Learning Objectives

After completing this continuing education course, nutrition professionals will be better able to:

1. Distinguish teaching assessments from anthropometric, lab, and clinical assessments.

2. Compare the various types of teaching assessments—formal, informal, formative, and summative—and when they are performed.

3. Determine how and when to use teaching assessments in the health care classroom.

4. Appraise the effectiveness of assessments that help teach.

Examination

1. Educational assessment refers to which of the following?

a. Evaluations of learning gains

b. Measurements of nutrient intakes

c. Anthropometric measurements

d. A clinical evaluation of learners

2. What are assessments that teach?

a. Written exams given in a testing center

b. Evaluations of a teacher by superiors

c. Instruments that also reinforce learning

d. Departmental interviews of teachers

3. What is a final evaluation of an entire classroom experience called?

a. Final formative examination

b. Formal formative quiz

c. Informal formative exam

d. Summative assessment

4. What is a rubric?

a. A list of demands written by the teacher and presented to the students

b. A table of statistical information from research studies in medical journals

c. A scale that compares performance against a standard in categories

d. A test with multiple-choice, short-answer, true or false, and matching questions

5. Which of the following is the best way to gather data about the summative learning gains of individual class members?

a. Ask students to tell the teacher if the class was valuable

b. Give learners the same test before and after the class

c. Give the students questionnaires of their food preferences

d. Observe oral presentations by groups of students

6. Which of the following would be an effective formative assessment?

a. Reading a learner’s medical chart notes before class

b. A multiple-choice test given to the students at the end of class

c. A crossword puzzle of vocabulary words completed during class

d. An exit interview after a classroom learning experience

7. Which of the following are found in a rubric?

a. Categories of things the learners need to know and levels that describe performance

b. Levels describing various things the learners need to know and cells that describe performance

c. Tables describing things the learners need to know and cells that describe success or failure

d. Titles describing the learner’s performance and numbers that describe the topic headings

8. According to the material presented in this course, data for determining the success of health care classes can be best collected by which of the following means?

a. Nutrition assessment using anthropometric data

b. Assigning letter grades to class participants

c. Collecting formal summative assessment data

d. Intuitive assumptions of students’ understanding

9. Which of the following is an example of an effective assessment tool that can provide feedback during the classroom experience?

a. A short-answer quiz that’s scored in class

b. A posttest given following attendance at a class

c. A list of recommended books and websites

d. A rubric handed out to students after class

10. Which of the following is an example of an informal formative assessment?

a. An exit interview after a classroom learning experience

b. A teacher-led question-and-answer session during class

c. A classroom presentation with a formal structure

d. A written multiple-choice quiz midway through a class

References

1. Orlich DC, Harder RJ, Callahan RC, Trevisan MS, Brown AH. Teaching Strategies: A Guide To Effective Instruction. 7th ed. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2004.

2. Good, R. Formative use of assessment information: it’s a process, so let’s say what we mean. Practical Assess Res Eval. 2011;16(3):1-6.

3. Marzano RJ. The Art and Science of Teaching: A Comprehensive Framework for Effective Instruction. Alexandria, VA: Association for Curriculum Development; 2007.

4. Slotta JD, Linn MC. WISE Science: Web-based Inquiry in the Classroom. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 2009.

5. Stiggins RJ, Chappuis J. An Introduction to Student-Involved Assessment FOR Learning. Columbus, OH: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall; 2008.

6. Marzano RJ, Pickering DJ, Pollock JE. Classroom Instruction That Works: Research-Based Strategies For Increasing Student Achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development; 2001.

7. Tomlinson CA. Fulfilling The Promise Of The Differentiated Classroom. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development; 2003.

8. Falk JH. Free-choice environmental learning: framing the discussion. Environ Education Res. 2005;11(3):265-280.