Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 21, No. 8, P. 36

A survey of Today’s Dietitian readers found that failures in critical thinking about nutrition are prevalent among clients. Here’s how behavioral science can help RDs turn the tide so patients can make the best dietary choices to improve their health.

Dietitians often hear some unusual things, because clients, patients, and other members of the public have trouble parsing through the myriad claims they hear about nutrition. Failures in critical thinking about nutrition are pervasive, and RDs often educate and advise people who ignore evidence, don’t comprehend evidence, question the importance of evidence, or make unfounded inferences from available evidence. Failures in critical thinking can result in unnecessarily complicated diets instead of important dietary changes that really could improve health.

Behavioral scientists have been studying critical thinking failure for decades; much has been learned about why critical thinking failure occurs and what to do about it. Since dietitians are at the front lines of major nutrition issues, it’s beneficial to understand how behavioral science can improve communication tactics.

As a team of two behavioral scientists and a dietitian, we’ve been studying how RDs address critical thinking failure. In collaboration with Today’s Dietitian (TD), we surveyed its readers in April 2019, receiving almost 900 responses from RDs. In that survey, most respondents viewed critical thinking as a pervasive problem, with 62% of dietitians seeing “failures in critical thinking about nutrition (by consumers or patients)” every day or almost every day. Respondents also offered their views on the causes of critical thinking failure and what needs to be done about it. This article will discuss the survey responses, add a few observations from behavioral science research, and offer some recommendations.

Cutting to the chase, we will emphasize two major perspectives from behavioral science. First, critical thinking isn’t just about getting the nutrition facts right. Indeed, we argue that critical thinking has three dimensions: 1) Diligent Clarification (ie, getting the facts right), 2) Logical Reasoning (ie, making appropriate inferences from facts and understanding tradeoffs), and 3) Humble Self-Reflection (ie, recognizing uncertainty, both in science and in personal perceptions). Critical thinking can be defined as “the objective analysis of facts to form a judgment,” and all three dimensions are needed to do that well.

The second major behavioral science perspective is that the human mind evolved for action and reaction, not for thinking critically about nutrition. While human cultures have built great critical thinking institutions such as science, the individual human brain isn’t optimized for critical thinking. Nobel Prize–winning research (in economics) on human decision making has shown explicitly that there are many ways in which we’re “wired” to take mental shortcuts.1,2 An important implication is that we can’t start a dialogue about nutrition with the expectation of critical thinking. Instead, we must expect failures and develop communication skills to inform people who aren’t inherently prepared to think critically about nutrition.

What’s Behind Critical Thinking Failure?

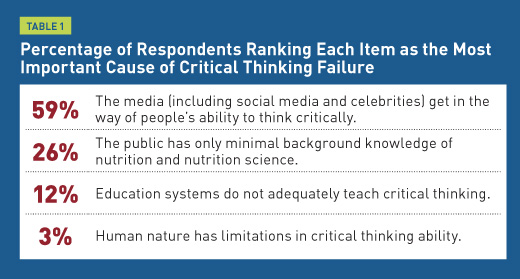

We asked TD readers to consider and rank four potential causes of failures in critical thinking about nutrition (by consumers or patients). Table 1 contains the four potential causes, along with the percentage of respondents who ranked that cause as the most important.

Only a few of you agreed with our view that the biggest barrier to critical thinking is human nature itself. We won’t push back on that too hard, but from a behavioral science viewpoint, the broad literature on cognitive biases (eg, overconfidence, confirmation bias) seems to merit inclusion of critical thinking in RD education (and in all general education).

The media certainly perpetuate critical thinking failures. And indeed, new research suggests that false news spreads faster and farther than true news in social media.3 Research is underway looking at how to improve critical thinking about information from the media.4 However, critical thinking failures were pervasive long before social media or mass media existed.

Without an appreciation of how the human mind works, it’s unlikely that nutrition professionals will succeed in spreading nutrition knowledge. They also may underestimate just how difficult it is to engage others to think critically about nutrition. On the other hand, adopting a behavioral science perspective will allow nutrition communicators to help others navigate the media landscape. Behavioral science can help communicators show people what to look out for, what to expect, and how to make better-informed dietary choices.

Preventing and Correcting Critical Thinking Failure

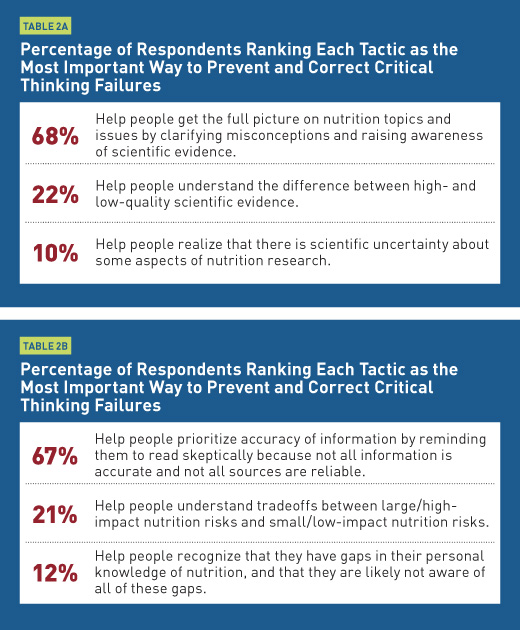

In two separate survey questions, RDs were asked to rank the importance of communication tactics to “prevent and correct” critical thinking failure by consumers or patients. The tactics in each question reflect the three dimensions of critical thinking: Diligent Clarification, Logical Reasoning, and Humble Self-Reflection. Tables 2a and 2b show a similar pattern in the tactics dietitians ranked as most important.

Within each question, the tactic that aligns with Diligent Clarification was most frequently ranked as the most important. Logical Reasoning tactics are a distant second, and Humble Self-Reflection tactics are a largely ignored third. While there’s no perfect answer, and intelligent people could disagree about priorities, we will try to make the case that the other two dimensions deserve at least as much attention as Diligent Clarification.

Encouraging Humble Self-Reflection

One of the most robust findings in the literature on psychological biases is a common phenomenon called “overconfidence.” People get gut feelings or intuitions that something is true and fail to recognize that this confidence isn’t based on an accurate inference from available evidence. The scientific method is explicit about the uncertainty that we should have. However, few individuals, even scientists, consistently succeed in acknowledging all of the uncertainty in daily life or in nutrition science.

Another form of cognitive bias is the knowledge illusion. This is the tendency for people to overestimate how well they understand the details of a process. In a famous study illustrating this phenomenon, research subjects who claimed to know how a bicycle worked were unable to explain how a bicycle’s parts (chain, crank, gears, etc) combined to move the rider along. The tendency is likely worse in nutrition, because everyone is familiar with food, and people have become accustomed to hearing terms such as “metabolism,” “antioxidant,” and “anti-inflammatory” without ever learning an accurate explanation of what’s involved. Yet people confidently use these terms to explain their avoidance (or embrace) of specific diets or food technologies.

When people are entrenched in a belief, education isn’t enough. Philip Fernbach, PhD, coauthor of the book The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone, has noted, “Our research shows that you need to add something else to the equation. … Extremists think they understand this stuff already, so they are not going to be very receptive to education. You first need to get them to appreciate the gaps in their knowledge.”5

This quote highlights one reason that focusing on the critical thinking dimension of Diligent Clarification may not be enough: When people feel they don’t need further education, simply providing additional information won’t help.

Conversion messages, such as testimonials from people who have changed their mind on an issue, may be one effective way to help people understand their own knowledge gap. A recent study found that people’s attitudes were more strongly influenced by a video clip of environmentalist Mark Lynas talking about his change from being opposed to genetically modified crops to favoring them than by a clip in which he discussed only being in favor of them.6

This technique of conversion messages may be useful to warm people up to the possibility that they don’t know as much about something as they think they do. Public health campaigns, such as the American Heart Association’s Go Red for Women, often feature stories of people discussing how they were once unaware of their disease risk and have since changed their outlook and habits.

Many dietitians use this technique in group programs, where participants can be prompted to describe how they changed their perception of their ability to adjust certain eating habits. In one-on-one counseling or in the media, RDs may use a story-telling approach to discuss how they, or a patient, had one thought about a particular food or eating habit, but learned that it was inaccurate and found a more effective way to address a problem.

Logical Reasoning and Risk Tradeoffs

Of course, while some education is essential, we would argue, however, that education should focus more on thought processes and the evidence process rather than simply sharing information. This leads to our second dimension, Logical Reasoning. It’s commonly understood that human emotion sometimes gets in the way of logical reasoning. Behavioral science research shows that people have enormous difficulty understanding basic probability, a nonemotional evaluation that’s fundamental in the understanding of risk.

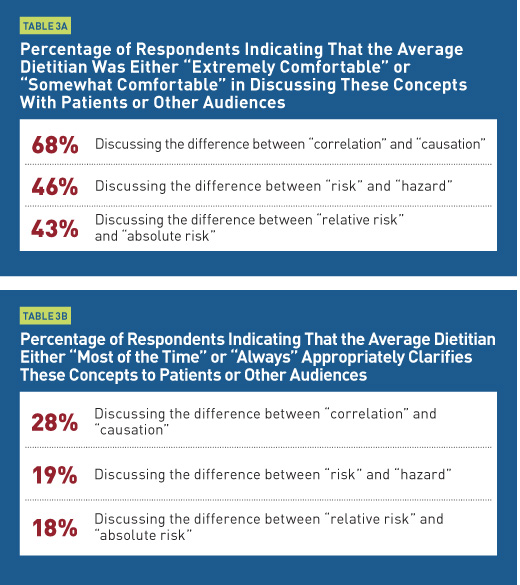

This shows up in many places in nutrition science, and the survey asked about three specific examples. First, people often confuse relative risk, the increased likelihood of an event, with absolute risk, the overall likelihood of the event. People also often confuse hazard, something that can cause harm, like a specific chemical, with risk, the likelihood that this hazard will cause harm with an expected exposure. Finally, people often confuse correlation, two things that have a linear relationship, as strong evidence of causation, one thing causing the other.

We asked RDs two questions about these concepts: 1) How would you describe the average dietitian’s comfort level in discussing these concepts with patients or other audiences? 2) How often do you think the average dietitian appropriately clarifies these concepts to patients or other audiences? Tables 3a and 3b show the responses.

Overall, responses suggest that dietitians aren’t fully comfortable discussing these concepts and, therefore, don’t often address them when talking with people. There are no quick fixes for this, and we think some useful continuing education programming could be developed for these concepts. For now, we address some of the challenges in talking about absolute vs relative risk through an example. Here, we will characterize the dietitian’s role using a Logical Reasoning tactic from Table 2b: Help people understand tradeoffs between large/high-impact nutrition risks and small/low-impact nutrition risks.

Let’s take an example (with numbers rounded and approximated slightly for ease of discussion). A widely cited research finding is that eating 50 g of processed meat daily (eg, four slices of bacon) increases the risk of developing colorectal cancer by about 16%.7 That’s the relative risk. The absolute risk of colorectal cancer in the United States is approximately 4%.8 The 16% increase in relative risk increases the absolute risk from 4% to about 4.6%. So eating 50 g of processed meat daily increases absolute risk by 0.6% (ie, 4.6%-4% = 0.6%). In other words, if 1,000 people ate four slices of bacon daily, 46 of them would develop colorectal cancer. If none ate four slices of bacon daily and all other risk factors were equal, 40 of them would develop colorectal cancer.

Some people will think the tradeoff of increased risk for bacon consumption is worth making; some people won’t. But it’s difficult to begin to understand the tradeoff without understanding the difference between relative and absolute risk. In addition, the absolute risk reduction from most narrow dietary changes offered by a popular book or oversensationalized headline will be much smaller, and probably zero.

If dietitians worry that the absolute risk in the example above will seem trivially small to their audiences, they can remind them of a couple of things. First, small absolute risk changes do add up, so overall impact of diet on disease risk is much larger than 0.6%. And second, even seatbelt use doesn’t reduce the absolute risk of death by more than 1%,9 yet 90% of Americans now wear seatbelts.10 And it’s a good thing, because the “small” reduction in absolute risk translates into more than 10,000 lives saved in the United States each year.11 From a public health perspective, “small” absolute risk reductions can represent very large public health wins.

Comparisons such as these may help people make decisions when eating choices are addressed in messages that seem to rely on exaggerated impressions of risk. For example, people may become fearful that even very limited consumption of a food or drink could doom them or their children to a major health problem. Confusion of hazard and risk complicates perceptions of risk, too. Dietitians can remind patients that just because studies have shown that exposure to very large doses of some chemicals cause health problems in mice, it doesn’t mean that a dose 1/1000th that size will cause any problems for patients and their families. A new Twitter account, @justsaysinmice, offers a series of humorous and informative tweets on this basic idea.

A detailed examination of risk communication is beyond the scope of this article. For now, we’ll emphasize our general recommendation: Communicators should try to make it easier for people to consider the magnitude of some risks vs others in their lives. Without that absolute sense of risk magnitude, people will find it difficult to understand the tradeoffs their choices entail.

Next Steps

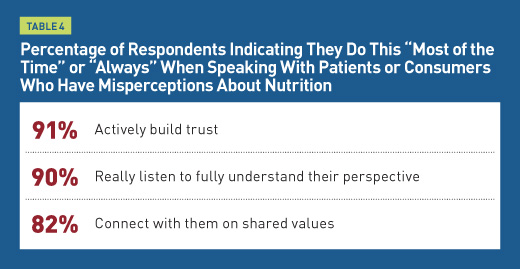

Dietitians already are doing many things well to address critical thinking failure. In Table 4, we examine the frequency of some of these practices when speaking with patients or consumers who have misperceptions about nutrition.

The answers are encouraging. And the concepts in this article may offer additional details and perspectives that can help guide dietitians in listening, connecting on shared values, and building trust with clients and audiences. We also hope that the topic of managing limitations in critical thinking will gain attention. Seventy-one percent of those surveyed said there weren’t enough good resources to help dietitians prevent and correct problems in critical thinking. Some are listed on our website ThinkingandEating.com. More are needed. Human nature won’t change, but culture and communication can.

— Jason Riis, PhD, is president of the consulting firm Behavioralize, and senior research fellow at the Behavior Change for Good Initiative at the University of Pennsylvania.

— Brandon R. McFadden, PhD, is an assistant professor of applied economics and statistics and research fellow at the Center for Experimental and Applied Economics at the University of Delaware.

— Karen Collins, MS, RDN, CDN, FAND, is a nutrition consultant specializing in cancer prevention and cardiometabolic health and nutrition advisor to the American Institute for Cancer Research.

Jason Riis, PhD, reports the following relevant disclosures: He serves as consultant and spokesperson for Ajinomoto, Bayer Crop Science, Conagra Brands, Produce for Better health, Texas Beef Council, and WW (Weight Watchers).

Brandon R. McFadden, PhD, reports the following relevant disclosures: He serves as consultant and spokesperson for Bayer Crop Science, Institute for Justice, and Texas Beef Council.

References

1. Kahneman D. A perspective on judgment and choice: mapping bounded rationality. Am Psychol. 2003;58(9):697-720.

2. Thaler RH. From cashews to nudges: the evolution of behavioral economics. Am Econ Rev. 2018;108(6):1265-1287.

3. Vosoughi S, Roy D, Aral S. The spread of true and false news online. Science. 2018;359(6380):1146-1151.

4. Pennycook G, Rand DG. Fighting misinformation on social media using crowdsourced judgments of news source quality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(7):2521-2526.

5. Sloman S, Fernbach P. The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone. New York, NY: Riverhead Books; 2018.

6. Lyons BA, Hasell A, Tallapragada M, Jamieson KH. Conversion messages and attitude change: strong arguments, not costly signals. Public Underst Sci. 2019;28(3):320-338.

7. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer: a global perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer. Published 2018.

8. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2019. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2019/cancer-facts-and-figures-2019.pdf. Published 2019.

9. What are the odds of dying from … . National Safety Council website. https://www.nsc.org/work-safety/tools-resources/injury-facts/chart. Accessed June 7, 2019.

10. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Seat belt use in 2017—use rates in the states and territories. https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812546. Updated June 2018. Accessed June 7, 2019.

11. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Occupant protection in passenger vehicles: 2016 data. https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812494. Published February 2018. Accessed June 7, 2019.