Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 18 No. 8 P. 28

An Overview of Its History, Its Benefits, and Where It Stands Today

Breakfast may be the most important meal of the day, particularly for children, who require energy for growth and development as well as for play and learning. Children who eat breakfast regularly are more likely to have favorable intakes of dietary fiber and total carbohydrate, and lower intakes of total fat and cholesterol, according to a study by Deshmukh-Taskar and colleagues in the June 2010 issue of the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Breakfast also seems to boost adequacy of B vitamins and vitamin D. As Gibson reported in Public Health Nutrition in December 2003, levels of these micronutrients among breakfast-eating children were 20% to 60% higher than those of their breakfast-skipping peers. Breakfast also may help keep BMI in check. Two large systematic reviews found that children who regularly consumed breakfast, including ready-to-eat cereal, were at lower risk of being overweight than kids who skipped breakfast.1,2

A nutritious morning meal also positively affects children’s behavior, cognitive function, and school performance, according to several studies, including one published in the December 2009 issue of Nutrition Research Review by Hoyland and colleagues.

Despite this seemingly overwhelming evidence, many children still begin their day without breakfast. Two-parent working families, early school hours, long bus rides, and the demise of family breakfast time make sitting down to eat in the morning a rarity. Food insecurity—lack of access to affordable, nutritious food—is another major breakfast barrier. Coleman-Jenson and colleagues reported in a USDA Economic Research Service Report in September 2012 that food insecurity affects 3.9 million American families with children, making these families nearly twice as likely to experience hunger as those without children.

According to a 2013 report on school breakfast by Share Our Strength’s No Kid Hungry campaign, a nonprofit school food advocacy group, three out of four teachers and principals reported observing students who are regularly hungry. Wesley Delbridge, RDN, a spokesperson for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, says the research shows that almost one-half of all children skip breakfast before going to school. “This can be very detrimental to the child’s physical and mental well-being,” he says. “Some families cannot afford enough food and these children have to go without breakfast. That is why it is so important to offer breakfast at school.”

A longtime proponent of the importance of eating breakfast, the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service has offered the School Breakfast Program since 1966. The School Breakfast Program began as a pilot program intended to improve the nourishment of young men bound for military service, but when the benefits for all students became apparent, it became permanent in 1975. The need for the School Breakfast Program is still present and growing. The program, which fed 500,000 participants in 1966, now feeds 13.7 million children across America. According to the USDA, the program aims to reach more eligible participants—only 80% of schools that provide school lunch currently also provide school breakfast. Although the School Breakfast Program is, at its core, federally funded and administrated by state education agencies, some states and municipalities make financial contributions to strengthen their specific programs.

All students, regardless of income, are eligible to consume school breakfast. However, the program’s target participants are low-income students at risk of food insecurity. Similar to the school lunch program, the School Breakfast Program works to enroll children who qualify for free and reduced-price meals. Children from families with incomes at or below 130% of the federal poverty level qualify for free, and those with incomes between 130% and 185% qualify for reduced-price breakfast.

In 2012, more than 10 million children who ate school breakfast received their meal for free or at reduced price. Schools with at least 40% of students qualifying for free or reduced-price meals can receive “severe need” payments, which can be 30 cents higher than regular meal payments.

According to the Food and Nutrition Service, the need for such programs is high; 77% of school breakfasts are served at “severe need” schools. The process of “direct certification,” which matches data from programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, allows schools to automatically enroll children with an established need for food assistance. Schools with a high percentage of low-income students can qualify for community eligibility, allowing them to serve universal free breakfast—breakfast at no cost to all students.

Breakfast Program Benefits

Research suggests that not just breakfast, but school breakfast specifically, pays off in terms of health, nutrition, and learning. Low-income children who eat school breakfast have better overall diet quality than those who skip breakfast or eat elsewhere.3 Furthermore, the benefits of school breakfast may extend to other family members, since the money saved on a child’s breakfast at home can cover other expenses.3

School breakfast appears to be effective at enhancing children’s health and well-being. Clark and Fox, in a supplement to the February 2009 Journal of the American Dietetic Association, found that children who ate school breakfast were more likely to meet or exceed standards for important micronutrients such as vitamin C, vitamin A, calcium, and phosphorus. In the same publication, Gleason and Dodd suggested that school breakfast participation may be associated with a lower probability of becoming overweight. Furthermore, according to Bernstein and colleagues in their USDA Evaluation of the School Breakfast Program Pilot Project, published in 2004 in the Nutrition Assistance Program Report series, it seems that students who eat school breakfast tend to have better attendance and fewer visits to the nurses’ office. They also seem to have better mental health, fewer behavioral problems, and less anxiety and depression, according to Kleinman and colleagues in a report in the January 1998 issue of Pediatrics.

Innovation Is Key

Traditionally, school breakfast has been a hot meal served in the cafeteria before the bell rings. This conventional service style cuts down on food packaging, provides flexibility to meal planners and servers, and allows for a variety of breakfast items to be served. At some schools, however, opening and staffing the cafeteria for breakfast is difficult, costly, or inconvenient.

A bigger problem administrators of the School Breakfast Program continue to work hard to resolve is the potential stigma that the traditional service style can involve: the labeling of school breakfast eaters as “poor kids.” The USDA and school districts have worked to democratize breakfast by encouraging alternative service styles and universal free breakfast, which has the double benefit of providing food to the greatest number of students and allowing for the greatest degree of anonymity.

Other types of innovation make a difference as well. Since students seem less likely to sit in the cafeteria and eat than in the past, new approaches to breakfast are needed. “The most nutritious breakfast is the one that students will actually eat,” says Dayle Hayes, MS, RDN, a school nutrition advocate and founder of School Meals That Rock. “Tweens and teens take eating on-the-go literally. They want quick, quick, quick. Successful programs meet students where they are with the food they want. Smoothies, yogurt parfaits, [and] hand-held breakfast sandwiches are being served at kiosks, carts, or fast lanes where students enter the building and at other hot gathering spots.”

Chow in the Classroom

An alternative to traditional service, breakfast in the classroom has been adopted by many schools. As its moniker suggests, this service style involves students eating breakfast, hot or cold, right in the classroom. Students pick up their food in the cafeteria or from a cart and report to their classroom to eat. According to the USDA, breakfast in the classroom can be accomplished without significant interruption or loss of instructional time. The USDA states that it takes about 10 to 15 minutes for children to consume breakfast; teachers can take advantage of this time for housekeeping chores such as taking attendance, making announcements, and collecting homework. In fact, the USDA reports that some teachers claim this style leads to improved productivity because students aren’t distracted by changing rooms to start their school day.

“Studies show that when breakfast is served in the classroom, participation increases along with academic performance and positive behavior,” Delbridge says. “Many school administrators feel that breakfast in the classroom cuts into the teaching time, teachers are annoyed with the extra work, and custodians may complain about clean up. However, the benefits of breakfast in the classroom far outweigh these issues.”

Hayes points out that many schools may be concerned about creating messes outside the cafeteria, but those fears shouldn’t outweigh the myriad benefits of a healthful breakfast.

New York City began serving universal free breakfast in 2003. Five years later, the city piloted the breakfast in the classroom program in an effort to increase breakfast “take-up,” or participation rates, by removing the stigma attached to school breakfast. Then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg opposed the program, siding with those who feared that many kids would eat breakfast at home and again at school, leading to more calories and potential weight gain.

However, a March 2016 study by Wang, Schwartz, and colleagues in Pediatric Obesity, suggested this was unlikely to occur. The researchers tracked nearly 600 middle-school students from fifth to seventh grade, observing those who ate no breakfast, ate breakfast at home or school, or ate both. Weight gain among students who ate a “double breakfast” was no different than that among all other students. In fact, the risk of obesity doubled among students who skipped breakfast or ate it inconsistently.

When the city was piloting breakfast in the classroom, the father of a high school senior quoted his son as saying, “There used to be a small group of kids who ate breakfast together every morning and kind of stuck together. When we got to school and there was breakfast in the classroom, everybody looked kind of skeptical. Then a big football player-type guy yelled, ‘Wow, free food!’ and he began to dig right in. For the first time, everybody was eating together, and it was so fun.”

In a report issued by the National Bureau of Economic Research in July 2014, Schanzenbach and Zaki studied the student impact in New York City schools that already had implemented breakfast in the classroom and those that had traditional, universal free breakfast. They found that both programs increased breakfast participation, although this was probably due to students shifting consumption from home to school or consuming multiple breakfasts. They also found little improvement in 24-hour nutritional intake, behavior, health, and school achievement. Similarly, Corcoran’s report on New York City’s breakfast in the classroom program in the summer 2016 issue of the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management suggests that breakfast in the classroom didn’t promote weight gain but also didn’t improve academic performance.

In 2015, The New York Times reported that the New York City department of education concluded that caring for the whole child would take precedence and that guarding against food insecurity is top priority. Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that in the 2017–2018 school year, breakfast in the classroom will be offered in all standalone elementary schools, serving 339,000 students, at a cost of $92.6 million including state, federal, and city contributions.

Other Service Styles

Grab ‘n’ Go: This style allows students to pick up a bagged or boxed breakfast when they get off the bus, or enter the school or a classroom. Some schools use mobile carts to facilitate distribution. Depending on school rules, students typically have the freedom to eat the meal where they want. This method allows for serving cold and hot items. With Grab ‘n’ Go, there may be concerns about clean up or organization. According to the USDA, Grab ‘n’ Go works best for schools that have crowded or off-limit cafeterias or gyms, a large number of students to feed in a short time, and teachers, administration, and custodial staff who support the breakfast program.

Breakfast after first period: Also called a “nutrition break” or “second chance breakfast,” this service style usually involves a meal between 9 AM and 10 AM. It’s generally served in grab ‘n’ go bags and distributed from mobile carts or tables set up where students pass by frequently or gather to socialize. This can be a sound strategy for schools that lack time first thing in the morning to serve breakfast. It also can help schools with minimal eating space or buses that arrive late. “In elementary schools, the biggest challenge is timing—making sure that students get to school with enough time to eat. Alternative breakfasts like breakfast after the bell overcome this obstacle ensuring that every child has the fuel they need,” Hayes says.

Breakfast on the bus: This service style can be helpful to school districts in which children have long bus rides or that have buses that arrive early in the morning to take students to school. Children receive their breakfast in a bag before they board the bus. This method also saves instructional time and cuts back on the responsibility of at-school kitchen and custodial staff.

Legislation

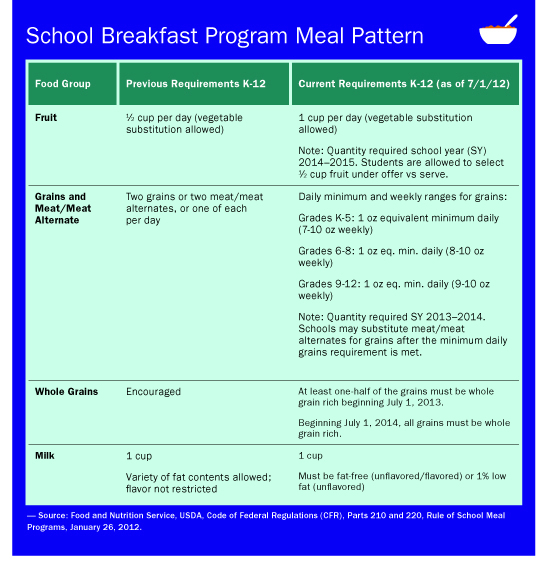

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA) of 2010, which expired last year, represented the first major overhaul of child nutrition programs, including the School Breakfast Program, in history. HHFKA brought school nutrition programs in line with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, adding more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and trimming sugar, sodium, and trans and saturated fats. It also employed specific calorie ranges for different age groups. In addition, the law simplified the process of qualifying children for free and reduced-price meals.

Despite its merits, the School Breakfast Program, like many other child nutrition programs, faces threats to its funding and challenges to long-sought-after changes. Congress currently is considering the Child Nutrition and WIC Act of 2016, which would renew but perhaps also alter current school breakfast regulations.

On May 18, the House of Representatives’ Education and Workforce Committee reauthorized “The Improving Child Nutrition and Education Act of 2016.” According to the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC), a Washington, DC-based advocacy group, the bill weakens community eligibility, impacting about 7,000 of the 18,000 schools currently participating in the program. FRAC also claims the bill would eliminate the option to participate in universal free breakfast for students at 11,000 additional schools.

The bill also makes it more difficult for those who participate in other food assistance programs to receive direct certification. Meanwhile, the Senate version of the bill calls for fewer changes to current regulations.

Opportunities for Dietitians

RDs have many roles to play in the School Breakfast Program—from consulting with schools on menu planning to promoting and marketing breakfast at the school, community, and policy levels. RDs can speak to local school administrators about using the expertise of an RD to create a breakfast program, especially one featuring breakfast in the classroom. They can meet with organizations such as parent-teacher associations to explain the program’s costs and benefits.

RDs also can help write and locate grants to subsidize breakfast programs. And they can contact legislators to discuss upcoming legislation that may threaten hard-won upgrades to program funding and standards.

There are several organizations, including FRAC and Share Our Strength’s No Kid Hungry Campaign, that use the knowledge of food security and nutrition experts to promote school breakfast and other food assistance programs. Corporations that have partnered with No Kid Hungry include Kellogg’s and Weight Watchers. Walmart and Sodexo also have advocated for and funded school breakfast research.

Hayes says RDs are invaluable to school breakfast programs. “Like any foodservice operation, school nutrition programs succeed by giving breakfast customers what they want—we keep them coming back. Savvy directors, many of whom are RDNs, carefully watch the latest trends in the food industry that kids want and see at their local food courts and fast food outlets,” she says. “Many directors focus on direct communications with students and meet with student councils and other groups to find out what kids want to see in their cafeterias.”

In the end, it all comes back to school children beginning their day the right way. “Whether it’s breakfast at home, breakfast in the school cafeteria, or breakfast in the classroom, all kids should be starting their day with a healthful, balanced breakfast,” Delbridge says.

— Christen Cupples Cooper, MS, RDN, is a doctoral candidate in nutrition education at Teachers College at Columbia University in New York City.

References

1. Szajewska H, Ruszczynski M. Systematic review demonstrating that breakfast consumption influences body weight outcomes in children and adolescents in Europe. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010;50(2):113-119.

2. de la Hunty A, Gibson S, Ashwell M. Does regular breakfast cereal consumption help children and adolescents stay slimmer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Facts. 2013;6(1):70-85.

3. Basiotis PP, Lino M, Anand RS. Eating breakfast greatly improves schoolchildren’s diet quality. Nutr Insight, 15. Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion; 1999.