Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 18 No. 8 P. 14

Learn how to help patients when a gluten-free diet doesn’t jumpstart healing.

As nutrition experts are well aware, treatment of celiac disease requires a strict, lifelong gluten-free diet. Unfortunately, some people fail to get better on the diet and may be considered to have nonresponsive celiac disease.

“Someone with nonresponsive celiac disease has either persistent or recurrent signs or symptoms that are associated with celiac disease, despite maintaining a gluten-free diet for one year,” says Maureen Leonard, MD, at the Center for Celiac Research and Treatment at Massachusetts General Hospital for Children in Boston. This includes persistent small intestinal damage (villous atrophy) and also may include persistent physical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fatigue.1 People with nonresponsive celiac disease also may have low levels of certain nutrients, such as iron, vitamin B12, and folate, due to malabsorption.2

Taking a Closer Look

Leonard explains that patients with nonresponsive celiac disease can be divided into two groups: primary and secondary. In primary nonresponsive celiac disease, the patient initially fails to respond to the gluten-free diet and doesn’t see improvement in symptoms. In secondary nonresponsive celiac disease, the patient may have been doing well for some time but then has a relapse in symptoms or develops new symptoms that can be associated with the condition.

“Usually when someone is newly diagnosed with celiac disease and begins the gluten-free diet, they start to see some relief in symptoms within the first two weeks, although progress may be slower in other people, as it takes time for the gut to heal,” says Pam Cureton, RDN, LDN, also from the Center for Celiac Research and Treatment. “By 12 months on the gluten-free diet, we expect celiac antibodies to normalize, although complete intestinal healing may take longer, such as if celiac disease has been undetected and uncontrolled for a while,” Cureton says.

Those with dermatitis herpetiformis, which is a blistering skin manifestation of celiac disease—with lesions most commonly on the elbows, knees, and buttocks—accompanied by inflammatory changes in the small intestine, may find their skin rash is nonresponsive to the gluten-free diet and require prolonged use of the medication dapsone.3

Prevalence

“Nonresponsive celiac disease affects between 7% and 30% of patients with celiac disease treated with a gluten-free diet,” says Melinda Dennis, MS, RD, LDN, nutrition coordinator of the Celiac Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Dennis was published on this subject in the April 2007 edition of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Both adults and children may experience nonresponsive celiac disease. By far, the most common cause of nonresponsive celiac disease is failure to adhere to the prescribed gluten-free diet, either voluntarily or unintentionally.1 In other cases, symptoms may not be related to gluten exposure and instead may be due to associated conditions, such as microscopic colitis, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, pancreatic enzyme insufficiency, or lactose or other food intolerances.2,4

According to data presented at the American College of Gastroenterology 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting, 23% of 754 children with biopsy-confirmed celiac disease diagnosed at Boston Children’s Hospital from 2008 to 2012 met criteria for nonresponsive celiac disease.5 However, gluten exposure accounted for 40% of nonresponsive celiac disease cases in this study.

Only a small percentage of individuals (up to 10% at celiac referral centers but much less elsewhere) have refractory celiac disease—truly not responsive to the gluten-free diet alone—and may require more aggressive therapies, such as a course of immunosuppressant medication and nutrition support, Leonard says.6 In very rare cases, those with refractory celiac disease may develop intestinal lymphoma.

In a study of nonresponsive dermatitis herpetiformis published in the January 2016 issue of Acta Dermato-Venereologica, scientists found that seven (1.7%) out of 403 patients followed since 1970 had an active dermatitis herpetiformis rash that wasn’t responding to the gluten-free diet, although their villous atrophy had resolved.3 So, nonresponsive dermatitis herpetiformis may carry less risk of complications than nonresponsive celiac disease, although data are limited. Notably, in this study, two of the seven nonresponsive dermatitis herpetiformis patients had significant lapses in their gluten-free diet.

Is Gluten Sneaking In?

It’s crucial to dig deeper to determine whether a patient with celiac disease is truly nonresponsive to the gluten-free diet. RDs with expertise in celiac disease play a vital role in this process. Even if nonresponsive celiac disease patients insist they’re avoiding all gluten, the RD should request they keep detailed food records of what they typically eat and carefully review every aspect of their diet.

“Dining out is a common source of inadvertent gluten exposure, since people have the least control over their food,” Dennis says. She also keeps an “Oops list” of gluten sources that patients may overlook. It includes things like gluten-contaminated grills, toasters, and fryers, as well as supplements, medications, beer, and faith-based items, such as communion wafers and matzo.

“Patients sometimes overlook malt,” Cureton says. Malt extract, malt flavoring, malt syrup, and malt flour are derived from barley, a gluten-containing grain, unless another source is listed.7 So none of these ingredients is safe for a person with celiac disease.

Another tricky ingredient is yeast extract, a flavor enhancer. “Sometimes we find that yeast extract contains barley,” says Tricia Thompson, MS, RD, founder of Gluten Free Watchdog, LLC (glutenfreewatchdog.org), which tests gluten-free foods for gluten contamination. She advises that if you see yeast extract or autolyzed yeast extract in a food not labeled gluten-free, contact the manufacturer and ask whether spent yeast from beer manufacturing is the source, in which case it may be contaminated with malt and gluten-containing grains.8

Grains, Flours, and Cross-Contact

Thompson advises that patients with celiac disease buy only naturally gluten-free grains and flours that are labeled gluten-free. “Naturally gluten-free grains and flours can be contaminated with wheat, barley, or sometimes rye,” Thompson says. Although oats are easily contaminated (and may be problematic for a small subset of celiac disease patients even if they’re not contaminated), other gluten-free grains may be contaminated, too—whether in the field, during harvesting and transport, at the mill, or in the processing plant.

According to Thompson’s research in the June 2010 issue of the Journal of the American Dietetic Association, seven of 22 inherently gluten-free grain and flour product samples (32%) not labeled gluten-free, including millet, sorghum, and soy flour, contained average gluten levels well above 20 parts per million (ppm).9 As of August 5, 2014, the FDA requires foods labeled gluten-free to contain less than 20 ppm of gluten, although it doesn’t specifically require manufacturer testing.10 Thompson doesn’t recommend home test kits for gluten contamination in food since there are many intricacies involved with accurate testing.11

Thompson led another study that evaluated gluten levels in 158 different foods labeled gluten-free and sold in the United States, which was published in the February 2015 issue of the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition.12 Approximately 95% of labeled gluten-free foods tested for the study had less than 20 ppm of gluten. Those that exceeded the 20-ppm limit were varied and included a hot beverage, bread product, breadcrumbs, crisp bread, a cookie, hot cereal, a spice, and a tortilla.

Gluten Contamination Elimination Diet

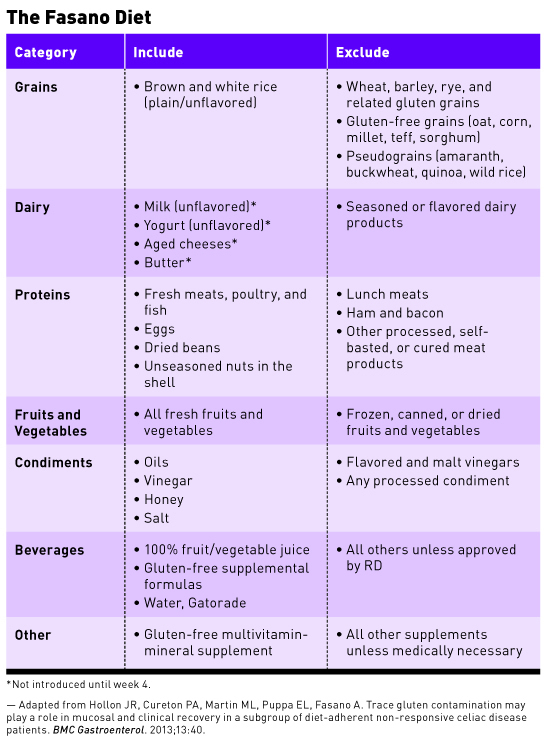

Given the challenges with gluten contamination, how can a person with nonresponsive celiac disease be certain they aren’t consuming gluten? A newer strategy is the gluten contamination elimination diet, sometimes called the Fasano diet, which Cureton worked with celiac expert Alessio Fasano, MD, to develop.

The gluten contamination elimination diet (see table) primarily consists of whole, unprocessed foods and omits all grains except rice, with the aim of greatly reducing the chance of inadvertent gluten exposure, including amounts <20 ppm, to which some nonresponsive celiac disease patients may be sensitive.1 It also requires people to eat out as little as possible, if at all. Cureton says that some negotiation of the rules concerning the gluten contamination elimination diet may be needed on an individual basis, such as for frequent business travelers.

The gluten contamination elimination diet is temporary—it’s typically prescribed for only three to six months, and the intent is to calm nonresponsive celiac disease patients’ hypervigilant immune systems and return them to a lower state of gluten reactivity typical of most celiac disease patients, Leonard says. It also should be done under RD supervision to ensure nutritional adequacy and appropriate use. The patients’ symptoms and celiac serology (typically tTG IgA) are reevaluated after three months, although it should be noted that normalization of the tTG doesn’t necessarily correlate with healed small intestine mucosa, and a repeat duodenal biopsy is suggested to confirm. If the gluten contamination elimination diet doesn’t improve symptoms within three to four months, then it’s probably not going to work, Cureton says.

In a February 2013 study in BMC Gastroenterology, Cureton, Fasano, and colleagues reported the results of 17 patients (ranging in age from 6 to 73) with nonresponsive celiac disease who completed the gluten contamination elimination diet after meeting with an experienced dietitian to ensure no sources of gluten could be identified.1 Fourteen patients (82%) got better on the gluten contamination elimination diet, and 11 (79%) were able to return to a traditional gluten-free diet without a recurrence of symptoms or increase in celiac serology, and showed normal villi on repeat biopsy. What’s more, five of the six patients who had been diagnosed with refractory celiac disease before the gluten contamination elimination diet responded to the diet and so were able to avoid corticosteroids or immunotherapy.

Other RDs have networked with Cureton for guidance and tips on implementing the gluten contamination elimination diet. Cureton developed an in-depth patient handout with diet survival tips and recipes. (RDs can contact her for details at pcureton@peds.umaryland.edu.) “The hardest thing with the gluten contamination elimination diet is that you can’t just grab something premade to eat, but I think a lot of people come away from it eating a lot healthier and being more creative in the kitchen.”

— Marsha McCulloch, MS, RD, LD, LN, is a nutrition writer and consultant based in South Dakota.

References

1. Hollon JR, Cureton PA, Martin ML, Puppa EL, Fasano A. Trace gluten contamination may play a role in mucosal and clinical recovery in a subgroup of diet-adherent non-responsive celiac disease patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:40.

2. Nasr I, Nasr I, Beyers C, Chang F, Donnelly S, Ciclitira PJ. Recognizing and managing refractory celiac disease: a tertiary center experience. Nutrients. 2015;7(12):9896-9907.

3. Hervonen K, Salmi TT, Ilus T, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis refractory to gluten-free dietary treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(1):82-86.

4. Chang MS, Green PH. A review of rifaximin and bacterial overgrowth in poorly responsive celiac disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5(1):31-36.

5. Veeraraghavan G, Kaswala DH, Kurada NE, et al. Etiologies and clinical features of nonresponsive celiac disease in children under the age of 18 years. Paper presented at: American College of Gastroenterology 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting; October 19, 2015; Honolulu, HI.

6. Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. Classification and management of refractory coeliac disease. Gut. 2010;59(4):547-557.

7. Thompson T. Barley malt ingredients in labeled gluten-free foods. Gluten Free Dietitian website. http://www.glutenfreedietitian.com/barley-malt-ingredients-in-labeled-gluten-free-foods/. Updated October 3, 2010. Accessed May 31, 2016.

8. Thompson T. Update on gluten-free status of yeast extract. Gluten Free Dietitian website. http://www.glutenfreedietitian.com/update-on-gluten-free-status-of-yeast-extract/. Updated February 7, 2013. Accessed May 31, 2016.

9. Thompson T, Lee AR, Grace T. Gluten contamination of grains, seeds, and flours in the United States: a pilot study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(6):937-940.

10. Questions and answers: gluten-free food labeling final rule. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/

Allergens/ucm362880.htm. Updated May 2, 2016. Accessed May 31, 2016.

11. Thompson T, Méndez E. Commercial assays to assess gluten content of gluten-free foods: why they are not created equal. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(10):1682-1687.

12. Thompson T, Simpson S. A comparison of gluten levels in labeled gluten-free and certified gluten-free foods sold in the United States. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(2):143-146.