Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 21, No. 4, P. 46

Suggested CDR Learning Codes: 5125, 5370, 5390

Suggested CDR Performance Indicators: 9.6.3, 9.6.4, 9.6.6, 10.2.5

CPE Level 2

Take this course and earn 2 CEUs on our Continuing Education Learning Library

While bariatric surgery remains the most effective treatment/intervention for morbid obesity, a subset of bariatric patients has been shown to experience weight regain as early as 18 months post surgery.1-3 Growing evidence shows a relapse into previous eating habits and the development or reemergence of eating disorders, disordered eating, and maladaptive eating patterns in the early years after bariatric surgery, behaviors that can lead to significant weight regain.2,4,5

Nutrition professionals must recognize obesity as a chronic disease with the potential for relapse and weight regain, and that these will be perpetual challenges to weight loss after bariatric surgery intervention.5 The inaccurate belief that bariatric surgery is a miracle cure for obesity must be corrected. To reach and maintain optimal weight loss, it’s essential that individual barriers are addressed and bariatric patients continue with regular follow-ups and interventions.6 Early intervention often can reduce patient risk of regaining a significant amount of weight.7 For the patient who has had previous bariatric surgery with inadequate weight loss and/or weight regain and later seeks revision or conversion surgery (eg, gastric band to sleeve, revision to existing sleeve, sleeve to gastric bypass), the role of the RD in the patient’s experience is also critical.

This continuing education course reviews the determinants of inadequate weight loss and/or weight regain after bariatric surgery. Early intervention by bariatric RDs who can identify the determinants of regain often can reduce patient risk of significant weight regain and also assist in patient selection for candidates seeking revision or conversion surgeries.

Determinants of Weight Regain

The factors influencing obesity and weight loss are complex, as are the determinants of inadequate weight loss and/or weight regain after any type of bariatric surgery.8 Anatomical complications (eg, pouch enlargement, anastomotic dilatation, and staple line breakdown), medication side effects, and medical conditions (eg, pregnancy, hypothyroidism, hormonal adaptation, and chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease) may contribute to weight regain or suboptimal weight loss postoperatively, particularly in patients who choose gastric bypass or vertical sleeve gastrectomy procedures.6,7 For example, in an effort to reduce chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms such as heartburn, nausea, and regurgitation, patients may alter their eating habits, turn to grazing (excessive snacking), or use food or beverages to treat symptoms, which may lead to excess calorie intake and weight gain.6 In gastric band patients, pouch dilatation; band migration, erosion, or slippage; port issues (leakage, infection, and dislocation); or psychological intolerance (distress over having a foreign object implanted inside the body) to the band often result in significant weight regain by negatively affecting satiety, increasing food volume or dietary indiscretions, and decreasing physical activity levels.4,6,9

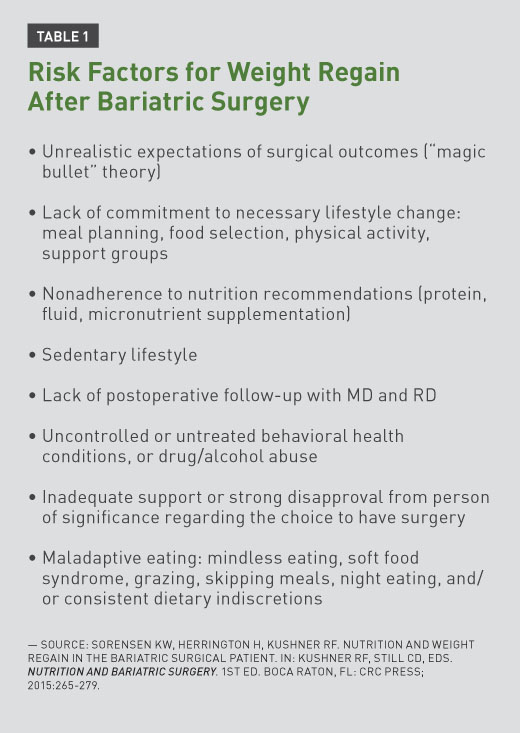

Anatomical and medical complications after bariatric surgery are comparatively rare. They’re more likely to occur in patients reporting the ability to tolerate much larger meals, increased hunger, or new/recurring acid reflux.7 A return to unhealthful habits and unaddressed or reemerging maladaptive eating patterns are more common barriers to long-term weight loss maintenance and contributing factors to weight regain after bariatric surgery.7,8 The bariatric dietitian often is the provider who has the most patient contact of all multidisciplinary team members, and it’s common for these RDs to mention such behaviors in team meetings. Such “red flag” behaviors seen in preoperative nutrition visits include having unrealistic weight loss goals, demonstrating resistance or ambivalence to meal and snack planning, repeatedly being a “no show” or cancelling appointments with RDs or other team providers, and exhibiting maladaptive eating behaviors due to lack of adequate social support (eg, loneliness or succumbing to pressure to eat bariatric-inappropriate foods from unsupportive family members). Unsurprisingly, if a patient seeking a revision or conversion after previous bariatric surgery has “failed” for nonanatomical reasons (such as lack of consistent support), it will be important for the patient to relearn that the surgery is only a tool to weight loss; untreated behavioral or motivational issues contributing to inadequate weight loss or weight regain after one surgery are likely to produce similar outcomes after a second procedure. Table 1 lists additional risk factors for weight regain after bariatric surgery.10

Behavioral Factors

Eating Disorders and Maladaptive Eating Patterns

Several researchers have identified “established” eating disorders (listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition [DSM-5]) such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS) in postoperative bariatric patients.4,6,11 Less is cited about other problematic eating behaviors that fall outside of this spectrum of eating disorders but still impact patients after bariatric surgery and may increase risk of weight regain. For example, with limited stomach capacity and the inability to consume an “excessive volume,” the criteria for binge eating disorder (BED) can’t be met objectively in bariatric surgery patients, even though the individual may experience many other behaviors of the disorder. Academics and clinicians may debate exact definitions of EDNOS, disordered eating, or maladaptive eating patterns, but night eating syndrome (NES), grazing, emotional eating, soft food syndrome, and postsurgical eating avoidance disorder (PSEAD) are real-world examples of challenging postoperative eating behaviors some bariatric patients face. While the presence of these behaviors after bariatric surgery likely is a continuation or relapse of similar preoperative disorders, the complex nature of both obesity and bariatric surgery may conceal overt symptoms of those disorders, making accurate diagnoses far more challenging.6 Current research shows that the existence of preoperative eating disorders isn’t always a contraindication for bariatric surgery, but investigations into inadequate weight loss after surgery have noted the postoperative development or reemergence of disinhibition (ie, unrestrained eating), binge eating, and grazing, which are related to postoperative weight regain.4,12,13 The underlying mechanism across these eating patterns is the patient’s experience of loss of control, which many patients note before surgery.4,14

Binge Eating

BED is defined as eating substantially large amounts of food within short periods of time, accompanied by a sense of loss of control and feelings of disgust, guilt, and/or depression after binge episodes.6 Estimates of preoperative bariatric patients meeting the criteria for BED range from 10% to 50%, but inadequate screening results in poor detection of the disorder before surgery.14,15 Therefore, these patients aren’t diagnosed or treated for BED before surgery, and certain aspects of the disorder (eg, loss of control with regard to food and eating) may emerge post surgery, potentially resulting in negative long-term weight loss outcomes.14,15 The physical restrictions of bariatric surgery on stomach capacity limit the extent to which full BED criteria (eg, consuming unusually large quantities of food) may be applied.14 Two studies by Ivezaj and colleagues confirmed loss of control eating and all criteria for BED, with the exception of large food volume, in sleeve gastrectomy patients.16,17 Until criteria are adjusted for bariatric patients and a “bariatric binge eating” subdisorder is written into a future edition of the DSM, a sense of loss of control over eating episodes and cumulative number of eating episodes may be more salient clinical features of binge eating and predictive of weight regain in this population than the excessive amount of food consumed per episode.14,18

An accurate preoperative diagnosis of BED by experienced behavioral health professionals is critical, as the underlying dynamics of the disorder usually persist after surgery.6 Effective treatment for BED or maladaptive eating used to cope with depression, anxiety, or trauma includes nutrition counseling, medical care, and follow-up, as well as individual, group, and family therapy.18 In the absence of such a multidisciplinary approach to treatment, it’s likely the eating disorder will persist or morph into another form of disordered eating (eg, grazing).18

Grazing

Grazing involves consuming smaller amounts of food continuously over an extended period of time accompanied by feelings of loss of control.14 Grazing affects many bariatric patients pre- and postoperatively, and though bariatric surgery restricts food consumed in one sitting, grazing is physiologically more possible than binge eating after surgery.14 Uncontrolled, excessive snacking throughout the day can result in excess energy intake and jeopardize long-term weight loss.6 With prevalence after bariatric surgery estimated at 31%, grazing increases risk of weight regain.14

Grazing is frequently triggered by stress, boredom, and emotional distress and worsens with “mindless eating” while watching television, surfing the internet, attending social functions, or working in foodservice settings.6 Grazing is linked with more behavioral health concerns as well as a higher risk of vomiting and gastrointestinal symptoms.6 It’s important to inform patients that regular vomiting postoperatively can cause nutritional deficiencies, dental caries, esophagitis, and gastric ulcers, all of which can further impact food choices and intake.6 For some patients, it may be necessary to correct the misperception that frequent vomiting helps to prevent weight regain.6

Due to reduced stomach capacity, patients with preoperative BED may be at risk of becoming grazers postoperatively, which can contribute to weight regain.12,14 Even in patients who lack a formally diagnosed eating disorder, a loss of control over eating continues after bariatric surgery and may be especially likely to increase around the two-year point.4,14,19 A loss of control when eating or grazing after surgery is associated with less excess weight loss, greater weight regain, and decreased perceived quality of life.4,14 Specifically, individuals who engage in grazing behaviors two or fewer times per week after surgery reported poorer percentage of excess weight loss and larger weight regain than those who didn’t.14

RDs should educate all bariatric patients about mindful eating and the importance of well-spaced, balanced meals and snacks throughout the day to assist with longer-term satiety, optimal nutritional adequacy, and appropriate consumption of calories.6 RDs can assist patients with developing eating strategies to distinguish between physical hunger and emotional “head” hunger.6 Gastric band patients need reinforcement that adequate fluid level in the band is important for continued weight loss; excessive restriction from a tighter band may prompt grazing on smaller portions to minimize discomfort, and inadequate restriction may result in additional snacking due to hunger.6

Night Eating

Night eating syndrome (NES) is characterized by morning anorexia, evening hyperphagia (consuming ~25% of daily caloric intake), and insomnia, and is considered a stress response.12 To differentiate between other sleep and eating disorders, NES episodes are conscious and aren’t considered “sleep-eating” or binges.12 Individuals with NES eat more meals and calories in the evening and report increased hunger with greater nocturnal snacking and preference for choosing high-carbohydrate snacks, with a negative impact on weight loss.12 Preoperative night eating behavior has been found to continue after bariatric surgery20 and is associated with a higher BMI and less satisfaction with surgery.12,20

Like BED, NES is associated with depression and anxiety, and patients referred for behavioral health treatment may respond well to psychological therapies and pharmacotherapy (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors).20 Though the effects of night eating on postoperative outcomes has received less attention than BED and grazing, the behavior seems to survive after surgery, and its relationship to weight loss outcomes warrants additional study.20

Other Maladaptive Eating Behaviors

Maladaptive eating may develop in some patients as an attempt to avoid vomiting after bariatric surgery and is linked to the development of food aversion, protein malnutrition, and micronutrient deficiencies, influencing long-term weight loss outcomes and quality of life.6 Patients who generally avoid solid foods and eat softer, high-calorie foods such as chocolate, candy, and ice cream consume excess calories, particularly from refined carbohydrates and saturated fats. Food choices of soups, crackers, and cheese by maladaptive eaters are considered easier to swallow than solid foods.6 Such overconsumption of softer, calorie-dense foods (“soft food syndrome”) provides inadequate nutrition and decreased satiety cues, which ultimately contribute to excessive energy intake and weight gain.6 Conversely, some patients engage in restrictive eating, failing to consume adequate calories due to an intense fear of stretching the stomach pouch and regaining weight, or preoccupation with weight and body image, which can lead to macro- and micronutrient deficiencies and eventual weight regain.6 One restrictive eating pattern has been labeled postsurgical eating avoidance disorder, or PSEAD, in which the patient eats very little to avoid weight regain or experiences an almost “phobic” reaction to food.21

Before and in months following surgery, healthful eating habits should be reinforced to prevent the onset of maladaptive eating patterns, gastrointestinal distress, and weight regain, with particular emphasis on making behavioral changes involving nutrition and food, such as eating slowly, exercising portion control, and using cognitive behavioral strategies to encourage mindful eating and appropriate food choices.2,5,19

It’s important to educate patients about the need to follow the postoperative diet progression as instructed, encouraging the transition from soft food texture and consistency to solids when appropriate, as eating solids will increase satiety and allow for greater variety, nutritional adequacy, and social acceptance of eating.6 While some patients have a fear of this transition and avoid moving on to solid foods, other patients may attempt solid foods far too early, which may cause several complications. Nonjudgmental and supportive preoperative planning with the bariatric RD will reinforce the postoperative diet stages with the patient to lessen some of the anxiety that triggers the behaviors on either end of this spectrum. With regular follow-up from multidisciplinary team members, patients are more likely to recognize maladaptive eating behaviors or food aversions, maintain adequate lifelong nutrition, and not rely on bariatric surgery alone to improve their weight loss outcomes and health benefits.6

Psychological Factors

Emotional Distress

In addition to the noted eating behaviors associated with inadequate weight loss and regain, psychological factors could compromise adherence to recommendations and weight maintenance.11 Issues with low self-esteem, impaired body image due to excess skin, alcohol dependence, and depression can trigger emotional or “loss of control” eating, reduced physical activity, and increased risk of weight regain.6,22 Screening regularly for these risk factors and providing the patient with additional support and resources may optimize weight loss outcomes.6

Because binge eating, grazing, and “loss of control” eating are linked with self-soothing, depression, and anxiety, further investigation via prospective, long-term studies into the psychological benefits of such postoperative eating patterns is warranted.14 Revised diagnostic criteria for eating disorders also are needed, particularly regarding maladaptive eating behaviors following bariatric surgery.18

Lack of Support

Some patients may lack support or face disapproval about their choice to have surgery from significant others, family members, friends, and colleagues. Those who choose not to publicly disclose the decision to have bariatric surgery may find lack of understanding and support from significant others. These patients should be encouraged to attend support groups or seek psychological counseling to assist them with their weight loss journey.

Nutrition professionals should remain current on the latest research about eating disorder treatments in relation to bariatric surgery and contribute to precautionary actions the multidisciplinary team takes before and after surgery.18 Guidance from the multidisciplinary bariatric team can support patients through their weight loss journey, help prevent the development of maladaptive eating behaviors, and improve their long-term weight loss outcomes.6

Nonadherence to Nutrition Recommendations

Patients may be inadequately prepared to make the major nutrition and eating behavior changes necessary for optimal weight loss after bariatric surgery, despite ample nutrition education before surgery. The bariatric patient’s nonadherence to nutrition recommendations can influence both short- and long-term weight loss due to excessive energy intake, inadequate micronutrient supplementation, and/or lack of physical activity.6 For those patients seeking a revision or conversion, the bariatric team members, including the RD, should determine how the patients have changed their expectations, habits, and behaviors in anticipation of the second surgery. What did not work for the patients the first time? What has changed? Though nutrition education and counseling continues to be key, the importance of a skilled behavioral health practitioner can’t be emphasized enough when discussing a multidisciplinary team approach in the bariatric setting. For those RDs with career aspirations in this setting, additional training in behavioral health or behavioral health nutrition is recommended.

Nutritional Factors

Liquid Calories

Patients should limit high-calorie and sweetened drinks, particularly carbonated and alcoholic beverages. High-calorie liquids have little effect on satiety but may result in inadequate weight loss or weight regain.6 Patients who struggle with solid food after surgery, particularly gastric band patients, are more likely to substitute caloric beverages.3,6 Regular postoperative RD visits can identify excessive intake of high-calorie or alcoholic beverages and provide patients with appropriate interventions to limit inappropriate fluid intake.6,13 In addition to hindering long-term weight loss, uncontrolled alcohol intake is linked with increased risk of alcohol abuse and dependence, as the consumption of alcohol replaces coping previously managed by excessive eating.6,23 Symptom substitution theory says “the successful elimination of a particular symptom without treating the underlying cause will result in the appearance of a substitute symptom.”6 Therefore, the bariatric RD and a skilled behavioral health clinician should preoperatively evaluate the patient’s eating and lifestyle behaviors to identify potential areas for concern and refer the patient for treatment as needed.6 A patient seeking bariatric surgery should be sober from alcohol or drugs of abuse for at least one year before surgery.6,23

To avoid “soft food syndrome” after bariatric surgery, patients should be encouraged to reintroduce solid foods in an appropriate texture progression for greater satiety and nutrition composition.6 Some patients hesitate with solid food progression due to fear of stalled weight loss, pain, nausea, or vomiting.6 However, these patients should be advised that remaining on less-filling liquids and puréed foods can limit satiety and resulting weight loss.

Protein Intake

Adequate protein intake after surgery is crucial for preservation of lean muscle mass, increased satiety, healthy nutritional status, and optimum weight loss.6 Suboptimal protein intake, resulting in muscle catabolism, may decrease resting energy expenditure up to 25% after surgery.6 In the absence of universal nutritional guidelines after bariatric surgery, individualize protein goals based on age, gender, and ideal body weight. Protein intake should average between 60 and 120 g daily.24

Because poor tolerance of certain protein foods (eg, red meat) may limit protein intake after bariatric surgery, patients should have regular postoperative visits with RDs to ensure their needs are being met, and RDs should teach them how to meet their requirements, including use of appropriate protein supplements.6

Vitamin and Mineral Requirements

Preoperative patient education typically includes information about the impact of preoperative malnutrition, gastrointestinal-related events/problems, emesis, and dumping on increased risk of malnutrition.19 After surgery, nutritional deficiencies can occur as nutrient availability from food is limited by volume restrictions, malabsorption of key nutrients, frequent vomiting, and/or poor patient compliance to the nutritional recommendations.6 Common postoperative nutrient deficiencies include protein, iron, calcium, and vitamins B12 and D.18 Patients with disordered eating are at risk of additional complications, including anemia, fatigue, neuropathy, pica, cognitive impairment, osteoporosis, and osteopenia.18 Risk of dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and cardiac arrhythmias (leading to heart attack or sudden death) also are increased in postoperative patients struggling with eating disorders.18

Patients must take multivitamins as recommended for life to help prevent micronutrient deficiencies, and the patient’s lab work should be checked every three to six months postoperatively for the first two years and monitored annually thereafter.19,24 Food cravings are a strong predictor of weight regain after bariatric surgery;13 reducing nutrition deficiencies can minimize fatigue and food cravings as well as improve long-term weight loss and quality of life.3,13

Role of the RD in Prevention of Weight Regain

Education and follow-up are key to the prevention of weight regain after bariatric surgery.7 Early identification of and counseling for nutrition, behavioral, and exercise barriers can spark a loss of the gained weight and resumption of weight maintenance.7 The continuing role of RDs in bariatric practice settings provides support and stability to patients who experience a return to preoperative unhealthful habits and regain. Incorporating relapse prevention skills used in traditional addiction recovery programs can be useful when working with bariatric patients postoperatively.

Patient Education

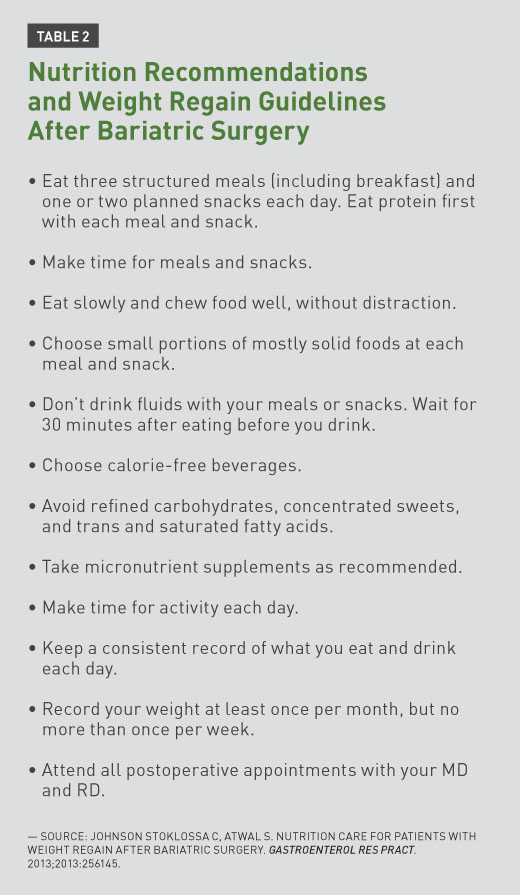

Pre- and postoperative education sessions provide the bariatric patient with practical knowledge, skills, and support to make the required nutritional, psychological, and lifestyle changes to optimize weight loss.6,19 Patients requiring six preoperative nutrition visits over six months often complain about the long period of time before surgery, and many bariatric dietitians respond that this time period is necessary to educate the patients about the large volume of knowledge to be learned and nutrition and lifestyle changes to be implemented in that time period. While stomach size isn’t altered before surgery, it’s important for patients to practice meal planning, portion control, mindful eating, chewing slowly, label reading, self-monitoring skills, and appropriate food selection before surgery. Frequent cancellations or no-shows may be an indication of a patient’s lack of commitment, motivation, or readiness. Table 2 illustrates a summary of nutrition recommendations for patients after bariatric surgery.19 Greater weight loss is directly related to frequency of consultations, supporting recommendations to deliver bariatric education by a multidisciplinary team of professionals who provide specialized advice.6 For patients who cite time, distance, or cost as barriers to follow-up, alternative methods of communication such as telephone, Skype, or online contact could be offered to maximize patient contact after surgery.6,8

Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring with a weekly weight record, maintaining a daily food/mood/activity log, and/or finding a daily “check-in buddy” will increase the patient’s sense of personal accountability for eating and lifestyle habits, which can be instrumental in preventing weight regain.6,13 In particular, a journal of daily food intake will increase patient awareness of eating patterns, and routine follow-up allows bariatric dietitians and other providers to identify nutritional inadequacies, food intolerances, poor food choices, or food aversions.6,25

Bariatric RDs are encouraged to reach out to patients for long-term follow-up, as adherence to nutrition appointments and recommendations has been shown to improve outcomes in patients struggling with weight regain. Faria and colleagues found that nutrition counseling for gastric bypass patients with weight regain two years after surgery was effective in reducing total body weight and body fat.26

Patients experiencing weight regain may feel ashamed or embarrassed that they’ve “failed” and may be reluctant to return to any member of the bariatric team; by reaching out to the patient in a compassionate and nonjudgmental way, the RD can offer support along with effective intervention to help the patient get back on track.

Eating Techniques

Providing simple guidelines to patients about helpful eating techniques can ease the transition to a new eating style after surgery.6 Mindful eating practices should be encouraged, including eating slowly, chewing foods well, and avoiding distractions from meals (eg, television, computer, and reading) to allow complete focus on feelings of fullness and satisfaction.6 Patients are encouraged to downsize to smaller plates, bowls, and eating utensils to help control portion sizes, and drinking any fluids with meals is discouraged.6 In general, patients should wait 30 minutes after eating before drinking fluids. While many of these eating techniques will make sense to patients because they relate to reduced stomach size and limited portion control, RDs also have several opportunities to help patients practice behavior modification as well.

Dining Out

Although data regarding dining out and eating fast food after surgery are scarce, frequent consumption of these foods could jeopardize weight loss.6 Patients should be encouraged to avoid fast food altogether, prescreen menus for healthful options before dining out, choose a bariatric-appropriate appetizer as an entrée, refrain from high-fat or high-sugar options, and avoid filling up on premeal extras or caloric drinks.6

Physical Activity

Increased physical activity constitutes an important long-term management strategy for weight loss and maintenance of muscle mass after bariatric procedures, and a low level of physical activity is a key predictor of weight regain postoperatively.5,6 A minimum of 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity is recommended daily, either cumulatively or at once, for long-term maintenance of significant weight loss.2,9 Increased physical activity levels after surgery are related to higher patient quality of life as well as weight loss compared with inactive bariatric patients, and should be recommended by the bariatric team.6

Support Groups

Support groups before and after bariatric surgery should promote an environment in which patients feel safe and comfortable, whether they’re doing well or struggling.7 Patients who feel welcomed and not judged when experiencing weight regain are more likely to attend support groups sooner, allowing for earlier interventions.7,27 Patients experiencing regain would benefit from support-group topics that focus on self-efficacy (ie, confidence in achieving and maintaining weight loss), avoidance of transfer addiction (ie, substituting one addictive behavior for another), and relapse prevention skills and education.

Patients with weight regain may have different needs than bariatric patients without regain and could benefit from separate behavioral interventions to target dietary nonadherence, disordered eating practices, or stress reduction following surgery.15 A 2015 pilot study by Himes and colleagues targeted dietary nonadherence, management of clinically relevant stressors, and reduction of grazing, binge eating episodes, and alcohol use using a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavior therapy.11 In the study, these treatments were expected to improve behavioral nonadherence with professional recommendations, stress management, and psychoeducation, and results showed that a combination of cognitive behavioral and dialectical behavior therapies helped jump-start weight loss, decrease grazing and binge eating behaviors, and slightly improve mood.11 These results suggest that offering support groups led by professionals trained in these therapies may be helpful interventions for patients experiencing weight regain.

Long-Term Follow-Up by a Multidisciplinary Team

Long-term measurements and follow-up by members of a multidisciplinary team are helpful in the prevention and timely treatment of weight regain, which tends to occur gradually.6 Team members who focus on diverse specialty areas are likely to identify and provide appropriate solutions for inadequate behavioral strategies, sedentary behavior, nutritional deficiencies, and medical complications related to bariatric surgery, all of which may contribute to inadequate weight loss or weight regain.6 There’s no doubt that bariatric patients face a host of challenges to lose weight and keep it off in the years following surgery. The support and expertise of bariatric team members preoperatively and during follow-up visits can ensure the safety, well-being, and optimal weight loss for patients who undergo this process.6

Final Thoughts

Patients who choose bariatric surgery must be educated to understand that obesity is a chronic disease; surgery is a tool to achieve significant weight loss, but inadequate postoperative adherence to recommendations can override that tool’s efficacy, leading to weight regain.7,10 RDs have a critical role in educating and counseling patients about following postoperative nutrition guidelines and should monitor patient anthropometrics closely for prevention of weight regain.8 RDs can optimize long-term weight loss by ensuring patients understand their selected bariatric procedures (including limitations), offering education before and after surgery, reinforcing patients’ use of self-monitoring skills, monitoring and tailoring nutrition supplementation, encouraging mindful eating practices and 60 minutes of daily physical activity, and providing supportive, nonjudgmental follow-up.6 After identifying factors that may contribute to regain, RDs can assist with patient care coordination to find appropriate solutions to help the patient cope with stressful relapse triggers.8 For long-term weight loss maintenance and prevention of weight regain after bariatric surgery, patients need continuous support from multidisciplinary teams to manage emotional eating, sedentary habits, and relapse to previous maladaptive behavior patterns.

— Mireille Blacke, MA, LADC, RD, CD-N, is an adjunct professor at the University of Saint Joseph in West Hartford, Connecticut; bariatric program coordinator at the Bariatric Center at Saint Francis Hospital in Hartford, Connecticut; and a freelance health and nutrition writer.

Learning Objectives

After completing this continuing education course, nutrition professionals should be better able to:

1. Demonstrate the role of the RD in the prevention of weight regain after bariatric surgery.

2. Evaluate the impact of nonadherence to nutrition recommendations on short- and long-term weight loss and risk of weight regain after bariatric surgery.

3. Assess the maladaptive and disordered eating patterns that may contribute to weight regain after bariatric surgery.

CPE Monthly Examination

1. The primary definition of disinhibition is which of the following?

a. Unrestrained eating

b. Restricted eating

c. Forgotten eating

d. Unplanned eating

2. In bariatric surgery patients with binge eating disorder, what is the most predictive feature of weight regain?

a. Eating large volumes of food within short periods of time

b. Feelings of disgust, guilt, or depression after a “binge”

c. Sense of loss of control with regard to food and eating

d. Postsurgical eating avoidance disorder

3. Which of the following is the common underlying mechanism between binge eating, grazing, and disinhibition?

a. Loss of control

b. Depression

c. Insomnia

d. Anxiety

4. What is the estimated prevalence of grazing after bariatric surgery?

a. 21%

b. 31%

c. 41%

d. 51%

5. Patients should be encouraged to reintroduce solid foods in an appropriate texture progression to avoid which of the following behaviors or conditions?

a. Soft food syndrome

b. Symptom substitution

c. Night eating syndrome

d. Grazing

6. Night eating syndrome is marked by which of the following symptoms?

a. Sleep eating

b. Evening anorexia

c. Morning hyperphagia

d. Preference for high-carb snacks

7. Which of the following is an appropriate nutrition recommendation for a postoperative bariatric surgery patient who’s eating solids?

a. Separate solids and liquids by 60 minutes. Wait 60 minutes before and after you eat before you drink.

b. Separate solids and liquids by 30 minutes. Wait 30 minutes after you eat before you drink.

c. Drink fluids first with each meal and snack.

d. Eat two meals, including breakfast, plus two snacks per day.

8. Weight regain after bariatric surgery is most likely due to which of the following problems?

a. Anatomical complications (eg, pouch enlargement, anastomotic dilatation, staple line breakdown)

b. Medical conditions (eg, pregnancy, hypothyroidism, hormonal adaptation, medication side effects, chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease)

c. Unaddressed or reemerging maladaptive eating patterns

d. Inadequate preoperative education and counseling

9. Which of the following strongly predicts weight regain after bariatric surgery?

a. Food cravings

b. Lack of support

c. Frequent vomiting

d. Dining out

10. Given the possibility of symptom substitution and transfer addiction after bariatric surgery, which of the following skills/strategies in preoperative nutrition visits may be helpful in preventing weight regain?

a. Cognitive behavioral therapy

b. Dialectical behavior therapy

c. Relapse prevention

d. Motivational interviewing

References

1. Bastos EC, Barbosa EM, Soriano GM, dos Santos EA, Vasconcelos SM. Determinants of weight regain after bariatric surgery. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2013;26(Suppl 1):26-32.

2. Blomain ES, Dirhan DA, Valentino MA, Kim GW, Waldman SA. Mechanisms of weight regain following weight loss. ISRN Obes. 2013;2013:210524.

3. Stewart KE, Olbrisch ME, Bean MK. Back on track: confronting post-surgical weight gain. Bariatr Nurs Surg Patient Care. 2010;5(2):179-185.

4. Meany G, Conceição E, Mitchell JE. Binge eating, binge eating disorder and loss of control eating: effects on weight outcomes after bariatric surgery. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2014;22(2):87-91.

5. Westerveld D, Yang D. Through thick and thin: identifying barriers to bariatric surgery, weight loss maintenance, and tailoring obesity treatment for the future. Surg Res Pract. 2016;2016:8616581.

6. McGrice M, Don Paul K. Interventions to improve long-term weight loss in patients following bariatric surgery: challenges and solutions. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2015;8:263-274.

7. Stegemann L. Treating weight regain after weight-loss surgery. Obesity Action Coalition website. http://www.obesityaction.org/wp-content/uploads/Treating-Weight-Regain.pdf

8. Valentine K. Options for treating weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Weight Manag Matters. 2014;12(4):5-7.

9. Pouwels S, Wit M, Teijink JA, Nienhuijs SW. Aspects of exercise before or after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Facts. 2015;8(2):132-146.

10. Sorensen KW, Herrington H, Kushner RF. Nutrition and weight regain in the bariatric surgical patient. In: Kushner RF, Still CD, eds. Nutrition and Bariatric Surgery. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2015:265-279.

11. Himes SM, Grothe KB, Clark MM, Swain JM, Collazo-Clavell ML, Sarr MG. Stop regain: a pilot psychological intervention for bariatric patients experiencing weight regain. Obes Surg. 2015;25(5):922-927.

12. Lynch A. Eating disorders and bariatric surgery. Weight Manag Matters. 2012;10(1):1, 22-23.

13. Odom J, Zalesin KC, Washington TL, et al. Behavioral predictors of weight regain after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2010;20(3):349-356.

14. Kofman MD, Lent MR, Swencionis C. Maladaptive eating patterns, quality of life, and weight outcomes following gastric bypass: results of an internet survey. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18(10):1938-1943.

15. Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Wilson GT, Labouvie EW, Brolin RE, LaMarca LB. Binge eating among gastric bypass patients at long-term follow-up. Obes Surg. 2002;12(2):270-275.

16. Ivezaj V, Kessler EE, Lydecker JA, Barnes RD, White MA, Grilo CM. Loss-of-control eating following sleeve gastrectomy surgery. Surg Obes Related Dis. 2017;13(3):392-398.

17. Ivezaj V, Barnes RD, Cooper Z, Grilo CM. Loss-of-control eating after bariatric/sleeve gastrectomy surgery: similar to binge-eating disorder despite differences in quantities. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;54:25-30.

18. Hillstrom K, Avila NM. BED, bulimia in bariatric surgery patients. Today’s Dietitian. 2014;16(1):12-18.

19. Johnson Stoklossa C, Atwal S. Nutrition care for patients with weight regain after bariatric surgery. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:256145.

20. Allison KC, Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, et al. Night eating syndrome and binge eating disorder among persons seeking bariatric surgery: prevalence and related features. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(Suppl 2):77S-82S.

21. Segal A, Kinoshita Kussunoki D, Larino MA. Post-surgical refusal to eat: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa or a new eating disorder? A case series. Obes Surg. 2004;14(3):353-360.

22. Sousa P, Bastos AP, Venâncio C, et al. Understanding depressive symptoms after bariatric surgery: the role of weight, eating and body image. Acta Med Port. 2014;27(4):450-457.

23. Conason A, Teixeira J, Hsu CH, Puma L, Knafo D, Geliebter A. Substance use following bariatric weight loss surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(2):145-150.

24. Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient—2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(2):159-191.

25. Sarwer DB, Faulconbridge LF, Steffen KJ, Roerig JL, Mitchell JE. Bariatric procedures: managing patients after surgery. Curr Psychiatr. 2011;10(1):19-A.

26. Faria SL, de Oliveira Kelly E, Lins RD, Faria OP. Nutritional management of weight regain after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2010:20(2):135-139.

27. Sodus MB. The art of facilitating successful bariatric surgery support groups for positive changes. Weight Manag Matters. 2015;14(1):2-4.