Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 21, No. 4, P. 24

Learn how sports training models are changing to improve young athletes’ overall health and long-term performance.

In today’s world of sports nutrition, keeping young athletes properly fueled is a big job. An estimated 45 million children and adolescents participate in youth sports in the United States, and 75% of US families with school-aged children have at least one child involved in organized sports.1 Ages range from the 6-year-old athlete participating at the local community sports club to the 17-year-old football player preparing for college sports.

Despite these statistics, there has been much less focus on early sports training and nutrition in younger athletes than that seen with older athletes. However, this trend is changing.

To work well with child and adolescent athletes, dietitians must understand more than just how to calculate their nutrient needs. RDs need to learn what their sports training entails, including the type, intensity, and duration of physical activity; their level of commitment; and the intricacies of adolescent development.

Young athletes are different from adult athletes in that their brains and bodies are constantly changing year to year, and they’re up against immense social pressures. Therefore, counseling techniques, education, and sports nutrition plans must reflect these differences.

Advancements in Today’s Youth Sports Training Programs

Because young athletes are much different from adult athletes, many changes are taking place in the world of adolescent sports training. Historically, traditional training models have put more emphasis on athletes playing the game and winning as well as early sport specialization, rather than on learning basic body movements and encouraging participation in multiple sports to learn multiple skills.

Experts who specialize in sports training for athletes younger than 12 have noticed problems associated with traditional competition models and early specialization. Two such experts are Richard Way, CEO of the Sport for Life Society, and Istvan Balyi, PhD, both of whom are architects of the Long-Term Athlete Development model, a framework for an optimal training, competition, and recovery program based on developmental age (ie, an individual’s maturation age) rather than chronological age.

Together, these Canadian researchers, along with Colin Higgs, PhD, authored the book Long-Term Athlete Development, which highlights the challenges of traditional training models. They review how encouraging sport specialization in young children leads to early drop-out rates, overuse injuries, early burnout, and a premature overemphasis on sport-specific skills. Their research also has shown that these children lack basic movement capabilities. Rather than learning the basics of body awareness and movements, traditional models encourage young athletes to learn sport-specific skills at a very young age, which potentially could limit their abilities as they advance in their sport or choose a different one.2

Sports organizations have taken notice of these issues and as a result have become part of a movement in the world of youth sports training to focus on long-term athletic development. This involves more focus on developing skills than on playing the game, encouraging multiple sport participation, practices vs competitions, and playing time vs winning. This new approach evaluates young athletes based on skill level, not necessarily age.3

The result is more fun, better athletes, and life-long players of the sport. Long-term athletic development is an evidence-based approach to coaching and developing young athletes that leads those in charge of youth athletic programs to implement best practices that provide proper training, competition, and recovery4; select exercise sequentially and progressively; educate coaches in all aspects of athletic development; provide for individual maturation variables (ie, physical, mental, emotional); and enable open communication among coaches, parents, and athletes.

To ensure success, this sports training must be supported by a sports nutrition plan for young athletes designed by a dietitian, so collecting detailed information about the training is a key component of nutrition counseling.

Understanding Adolescent Development

In addition to gathering important information about the training regimen, dietitians must learn the complexities of adolescent growth and development. Unlike adult athletes, young athletes have distinct nutritional requirements that depend on their stage of development. The stages of development, also known as the Tanner stages, include prepuberty, active puberty, and postpuberty.

Puberty is a process in which the body changes from that of a child to that of an adult. Children begin puberty at varying ages; girls, of course, face different struggles than boys as their bodies grow and change. The average age of puberty onset for girls is approximately age 11; for boys, it’s around age 13.5

During puberty, girls often experience a dramatic change in body composition—body fat levels can increase from 16% to 27%—and a slight decrease in lean mass. Boys also experience changes. As testosterone levels begin to rise, they gain lean body mass and experience decreases in body fat.5 These changes often lead to improvements in muscular strength and size.

These stages of development are more critical for determining energy needs and the ability to build muscle than chronological age. However, while the Tanner stages and skeletal ages of young athletes are the best predictors of nutritional and energy needs, this information isn’t always available to dietitians trying to develop a sports nutrition plan. RDs should be aware of the average age of puberty onset, then use the interview during nutrition counseling to collect information that can help them determine the athlete’s stage of development.

Assessment of Macronutrient and Micronutrient Needs

Prepubertal Athletes (~aged 6 to 12)

Nutritional needs of young athletes who haven’t yet reached puberty are similar for male and female athletes. At age 5, males and females are estimated to have only a 1% difference in body composition. That changes to an approximate 6% difference by age 10.5 This makes estimating nutritional needs much simpler for prepubertal athletes.

Dietitians can use the Dietary Reference Intakes to estimate basic nutritional needs for macronutrients, vitamins, and minerals. Active child athletes don’t require more micronutrients than nonathletes, but they may require more total calories to account for their increased energy expenditures.

Unlike for adult athletes, there have been no formulas developed to estimate the number of calories burned by young athletes when participating in different sports and at different intensities. It’s believed that children expend more energy than adults do when participating in the same activity, but there’s no evidence to prove it. Children, especially younger children, are less efficient in their movements, resulting in a higher calorie demand. As they become better trained in their sport, their energy demands likely decrease.6

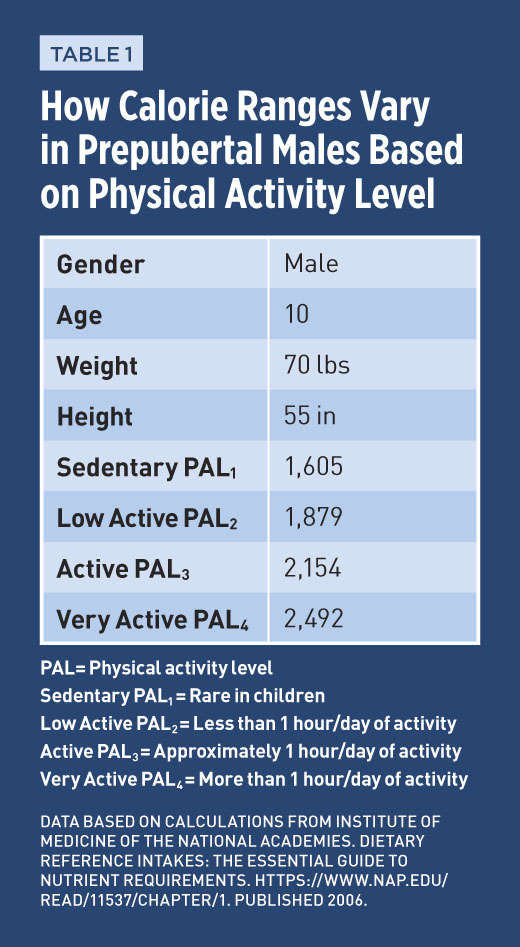

Though validated physical activity levels (PALs)—an athlete’s total energy expenditure over a 24-hour period divided by his or her basal metabolic rate—don’t exist for children, dietitians can use the PAL estimates for adult athletes as a starting point and adjust as needed. To estimate calorie needs, begin with the estimated energy requirement (EER) and adjust based on the level of activity.6

See Table 1 for an example of how calorie ranges vary in prepubertal males based on PAL.

Pubertal Athletes (~aged 10 to 14 in females; 12 to 16 in males)

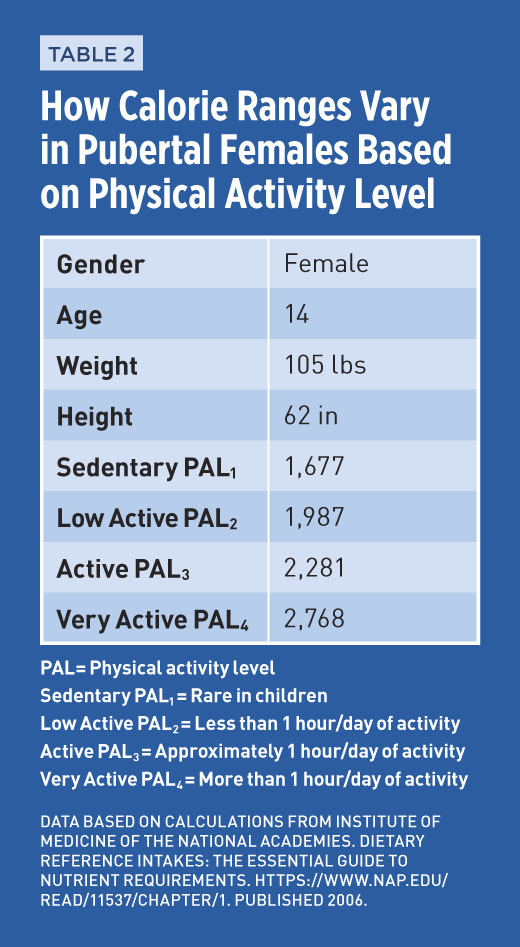

Calculating calorie needs of young athletes during puberty is more of a challenge. Not only do young athletes reach puberty at different ages but they also can be in different stages of development within puberty. Nonetheless, during puberty young athletes need extra calories to support linear growth and changes in body composition and bone mass. Determining exactly how many more calories are needed will vary for each athlete. Dietitians can use the EER to help determine total energy needs. The EER for children and adolescents is based on energy expenditure, requirements for growth, and activity level.

While the EER is a useful tool to estimate energy needs, remember that puberty is a process that occurs over time. Variations in growth rate and the amount of time and effort spent in physical training, practice, and competition all will impact individual calorie needs.

See Table 2 for an example of how calorie ranges vary in pubertal females based on PAL.

Postpubertal Athletes

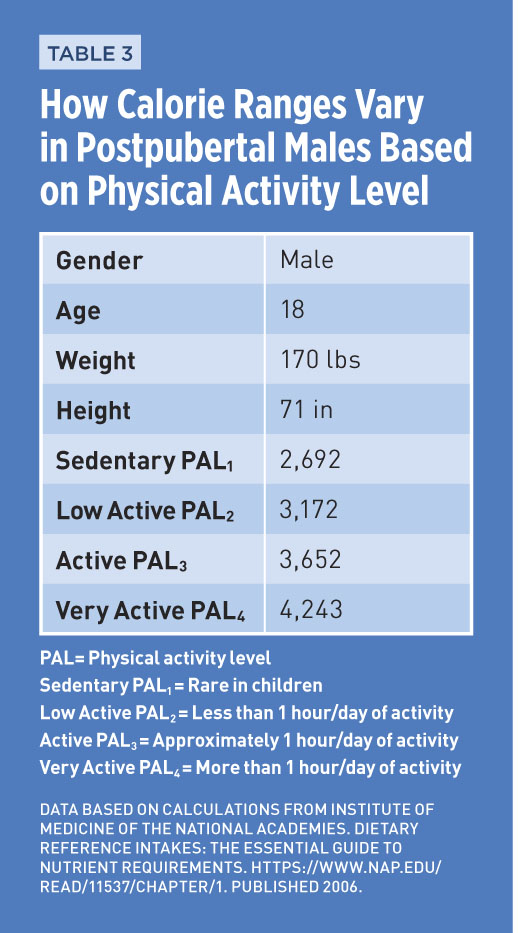

As athletes grow out of puberty, determining their nutrient needs becomes easier, but there’s still much to consider. At this stage, most athletes begin modifying their sports training to focus more on building muscular strength and size. Therefore, dietitians should tailor their sports nutrition plan to the athlete’s specific training goals.

Athletes approaching the college years often have body composition goals related to their sport. For example, a baseball player may want to focus on arm strength to improve his throw or decrease body fat to enhance running speed. These individual goals influence the athlete’s individual macronutrient needs.

See Table 3 for an example of how calorie ranges vary in postpubertal males based on PAL.

Putting a Sports Nutrition Plan Into Practice

Once dietitians determine young athletes’ nutritional and energy needs and have developed a nutrition plan in accordance with their developmental stage, they may encounter another challenge: getting clients to follow and adhere to the nutrition plan.

Coupled with the hormonal, physical, and psychological changes that occur during puberty, which can lead to poor self-esteem, poor body image, and disordered eating, young athletes are busy with sports training, competition, school, homework, and, in some cases, part-time jobs. They also may grapple with family issues that can lead to more undue stress and anxiety. All of these variables can have a negative impact on healthful eating in addition to other barriers they encounter daily.

Following are some of the most common hurdles young athletes face as they try to adhere to a nutrition plan and strategies to help overcome them.

Breakfast

Barrier: “I don’t have time to eat breakfast,” or “I’m not hungry in the morning. I feel nauseated.”

Solution: Remind young athletes that eating something is better than eating nothing. Help the athlete make a list of quick on-the-go breakfast ideas such as the following:

- 1/2 cup cereal, 2 T dried fruit, and eight nuts in a plastic bag with a hard-boiled egg;

- flatbread or bagel with deli ham or turkey and a slice of cheese;

- Greek yogurt, fruit, and granola;

- two servings of string cheese and a banana;

- granola bar and grapes; or

- one serving of milk or juice if nauseated.

School Lunch

Barrier: “My school lunch schedule is too early in the day,” “My lunch is too late in the day,” “They don’t serve enough food during lunch,” or “I don’t like what they serve at lunch.”

Solution: Encourage young athletes to do the following:

- Eat an early snack if they have a late lunch schedule or a late snack if they have an early lunch schedule.

- Buy or pack an extra lunch if the school doesn’t offer enough food. Some growing athletes need to eat two lunches or add items to their lunch to feel satisfied.

Homework and Work

Barrier: “I work part-time, so I don’t have time to get my homework done until very late at night.”

Such a work schedule can lead to unhealthful sleep patterns and ingesting stimulants such as caffeine from energy drinks. Young athletes who work may not be able to eat at their part-time jobs and/or they may not have access to healthful foods.

Solution: Teach the cycle that can occur from relying on energy drinks to stay awake (ie, Energy Drink→ Insomnia→ Fatigue→ Energy Drink→ Insomnia→ Fatigue), and do the following:

- Suggest they eat portable snacks and mini meals they can consume at work.

- Help them plan for what they can eat at work.

- Recommend they plan for breaks in their daily routine where they can squeeze in a meal or snack.

Travel

Barrier: “We rarely get to choose where the team eats after an away game,” or “I don’t think the coach is thinking about nutrition. Most of the time we stop at a fast food restaurant that doesn’t have high-quality protein choices.”

Solution: Encourage young athletes and parents to speak to their coaches and trainers and offer to investigate what restaurants serve healthful foods in the nearby towns where they play their games. If this isn’t a convenient option, do the following:

- Teach athletes how to pack a portable pantry that includes quick, nutritious on-the-go foods.

- Remind athletes they can pack microwaveable meals and stop at a service station to heat them.

- Discuss with athletes and parents what healthful items are available at grocery stores, service stations/mini-marts, fast food restaurants, and hotels.

Training and Practice

Barrier: “Sometimes I have practice before school, after school, or in the evenings, so it’s really hard to keep a set schedule for eating healthful foods.”

Solution: Help athletes learn to adopt flexible food schedules using the following strategies:

- Help them plan where to have team meals.

- Tell them what utensils to pack for eating on the go and how to pack portable meals.

- Suggest they bring a Thermos for beverages or soup.

- Recommend they bring a mini cooler filled with ice packs.

- Propose they assemble meals in containers or pack adult-size Lunchables.

- Rename breakfast, lunch, and dinner as meal 1, meal 2, and meal 3 to take the focus away from specific meals having to look a certain way. It’s OK that dinner is at 4 PM one day and at 7 PM the next day as long as they consume a mini meal or snack in between.

Sleep

Barrier: “I don’t get enough sleep,” or “I have difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep because I worry and feel anxious.”

Solution: Always discuss sleep when providing young athletes with nutrition counseling and do the following:

- Review the importance of sleep for their overall health and sports performance in ways they can understand. For example, quality sleep will give their bodies time to rest and recover, and they’ll incur fewer sports injuries.

- Explain that young athletes can make better decisions when they sleep well.

- Provide strategies from the National Sleep Foundation on how to prepare for sleep and fall asleep more easily.

The Big Picture

When working with young athletes, building trust is critical. Young athletes may hesitate to open up if they believe dietitians already have an opinion, so make sure to do more listening than talking.

Remember to adjust your communication style based on the developmental age of the athlete, not chronological age, and encourage athletes to open up. Ask to hear about their daily stressors and keep them top of mind as you create their nutrition plans. Be sure to remind young athletes that strict eating isn’t necessary to reach their goals. Discuss dietary flexibility and keep recommendations obtainable. Most importantly, help young athletes find solutions to their challenges by being a problem solver. Provide practical solutions to barriers as you work together to make healthful eating easy for young athletes.

— Heather Mangieri, RDN, CSSD, is author of Fueling Young Athletes and owner of Heather Mangieri Nutrition, a company that provides food, fitness, and nutrition consulting services to companies and individual clients.

References

1. Merkel DL. Youth sport: positive and negative impact on young athletes. Open Access J Sports Med. 2013;4:151-160.

2. Balyi I, Way R, Higgs C. Long-Term Athlete Development. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2013:5-9.

3. Meadors L. Practical application for long-term athletic development. National Strength and Conditioning Association website. https://www.nsca.com/education/articles/practical-application-for-long-term-athletic-development. Published May 2012.

4. Balyi I, Hamilton A. Long-term athlete development: trainability in childhood and adolescence: windows of opportunity, optimal trainability. http://static1.squarespace.com/static/55bed30ce4b009d3c6677cf0/t/

5670c5b89cadb635387a3cd1/1450231224115/Bayli_LTAD_Article.pdf. Published 2004.

5. Rogol AD, Roemmich JN, Clark PA. Growth at puberty. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(6 Suppl):192-200.

6. Carlsohn A, Scharhag-Rosenberger F, Cassel M, Weber J, de Guzman Guzman A, Mayer F. Physical activity levels to estimate the energy requirement of adolescent athletes. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2011;23(2):261-269.