Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 19, No. 6, P. 40

Learn about what they are, the different types for various diseases, and how they’re regulated.

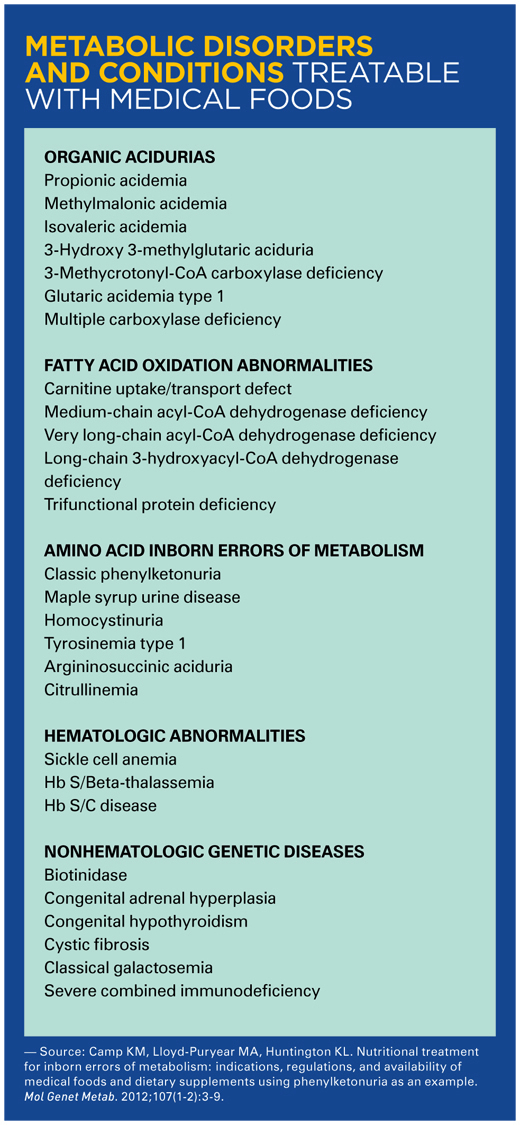

Hear the term “medical foods” and you’re likely to think of special formulas for those with inborn errors of metabolism, such as phenylketonuria (PKU), an inherited condition in which the body can’t metabolize the amino acid phenylalanine, or maple syrup urine disease, in which the body can’t metabolize branched-chain amino acids. To be sure, formulas for such conditions are a large part of the medical foods category, but the category has expanded and changed far beyond what it was in 1958 when Lofenalac, Mead Johnson’s infant formula for infants born with PKU, was introduced as a drug.

Today, medical foods have been developed for patients with malabsorption caused by Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, insomnia, ADHD, or inherited diseases of amino acids and organic acids. Medical foods are considered neither drugs nor dietary supplements and aren’t regulated as either one. They are their own category of products and since 1988 have been defined by the FDA as “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements, based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation.” They aren’t simply foods recommended by a physician as part of an overall diet to manage symptoms or reduce the risk of a disease or condition. New industry guidance addressing medical foods was published in May 2016 reestablishing this as the definition.1

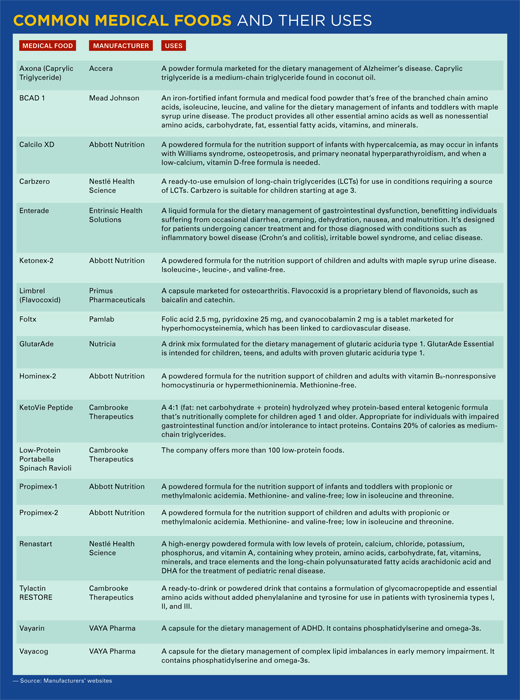

Medical foods generally fall into one of the following three categories:

• products with a full complement of nutrients except the offending nutrient (eg, phenylalanine or tyrosine), including Lofenalac, Ketonex-2, or Propimex;

• modular products, such as ready-to-drink beverages, tablets, and amino acid mixtures, including GlutarAde and Foltx; and

• low-protein foods that range from baked goods, pasta, and rice, to meat and cheese substitutes as well as snack foods.

Chronic illnesses, such as diabetes or obesity, or diseases that result from nutrient deficiencies, such as scurvy or pellagra, for which modifications in a regular diet can treat the disease, aren’t considered conditions for which medical foods can be labeled and marketed.

The regulation of medical foods is a hybrid of that for prescription drugs and dietary supplements, though it’s much closer to supplements than drugs. Medical foods are exempt from federal nutrition labeling requirements and those for health claims. Although medical foods are designed to be used only under the supervision of a physician, and can be labeled as such, labeling them as “Rx only” isn’t allowed. Despite their similarity to prescription drugs, they aren’t classified as drugs and aren’t subject to drug approval requirements, such as clinical testing for efficacy, premarket review, and FDA approval. Instead, all ingredients in a medical food must be on the FDA’s Generally Recognized as Safe list.

On the other hand, according to Kathryn Camp, MS, RD, CSP, former senior scientific policy analyst and scientific policy analyst to the Office of Dietary Supplements at the National Institutes of Health, infant formulas for inborn errors of metabolism are considered medical foods, but are regulated as infant formulas. Per the FDA’s Office of Food Labeling and Nutrition, there’s no federal requirement that prevents medical foods from being in pill or capsule form. Neither does the FDA maintain a comprehensive list of medical food products on the market. However, any facility that manufactures, processes, packs, or holds medical foods intended for consumption in the United States must register with the FDA and follow current good manufacturing practice regulations, which are enforced by the FDA.

And while medical foods aren’t considered drugs, most labels on medical foods state, “must be used under the supervision of a physician,” but the statement isn’t required and, paradoxically, a physician’s approval for use isn’t required for some online products labeled as “medical foods.”

Insurance Coverage

Just as complex as the definition and regulatory oversight, or lack thereof, of medical foods is insurance coverage for patients. “Insurance coverage is probably the biggest challenge for patients needing medical foods because reimbursement is highly variable,” says Marina Chaparro, MPH, RD, CDE, a pediatric dietitian and spokesperson for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. “Currently, there are no federal laws to mandate consistent coverage for medically necessary foods. Some insurance policies will cover a medical food only if it’s demonstrated to provide 50% of total energy needs.” Generally, however, while a physician’s order isn’t necessary to purchase a medical food, a physician must issue a written order that a medical food or formula is medically necessary for treatment for it to be covered by a health insurance policy. Even when covered, essential medical foods are sometimes categorized as “second-” or “third-tier” drugs and have high out-of-pocket costs. However, several states have passed legislation mandating a limit on out-of-pocket costs for specialty medications such as these. These limits range from $100 to $500 per month per medication, depending on the type of plan. Insurance companies are more likely to cover medical foods for inborn errors of metabolism than for, say, medical foods for sleep or ADHD.

In a 2013 survey, families requiring medical foods reported purchasing them primarily from pharmacies (34%), hospitals/clinics (18%), health departments (14%), and medical supply companies (12%). The survey also found that insurance companies often terminated coverage for these specialized products at age 21. In addition, Medicare Part D excluded the coverage of amino acid supplements.2

According to Camp, “While medical food companies have a history of providing products in critical situations (eg, during pregnancy and for newly diagnosed patients), this practice is primarily a stopgap measure until coverage can be established.” Health insurance has changed dramatically since 2013 and is predicted to undergo another sea change in the near future, making it difficult to counsel clients on how to obtain and pay for these specialized products. Annual costs for medical foods for an individual can range from $3,600 for an infant requiring infant formula to more than $26,000 for an adult male or a pregnant woman.3 Some companies, such as Cambrooke Therapeutics, have dedicated teams to help customers obtain insurance reimbursement coverage.

Where to Get Help

“Manufacturing companies of specialized formulas, such as Nestlé, Abbott, Nutricia, and others, offer assistance programs that teach parents how to advocate and obtain insurance coverage,” Chaparro says. Nonprofit organizations such as the Oley Foundation, provide donated supplies and specialized formulas to children and families in need of specialized enteral supplies for medical foods.

The Center for Advancing Health Policy and Practice at Boston University’s School of Public Health provides a state-by-state listing of mandates for coverage that was current as of November 2016. Extensive state-to-state differences exist in diagnoses covered, types of products and supplies covered, age and benefit limits, and individual mandates for private insurance coverage. Findings include the following:

• Six states have legislation specifically for medical foods required for children with PKU; five Medicaid programs only cover PKU, and two WIC programs and three Title V programs (federal/state programs to improve the health and well-being of women, particularly mothers, and children) cover only PKU;

• 35 states have legislative mandates for employer-sponsored insurance coverage of medical foods for genetic inborn errors of metabolism such as PKU, galactosemia, and maple syrup urine disease;

• 34 states provide coverage of medical foods through their Title V/CSHCN (Child with Special Health Care Needs) or other programs; and

• the language and vocabulary used in state statutes and legislation is highly variable and doesn’t always conform to clinical norms.

NORD, the National Organization for Rare Disorders, provides up-to-date information on where individual states stand on coverage of medical foods and provides links and information on getting involved with advocacy.

Recommendations

For dietitians who counsel clients and patients, especially those who are newly diagnosed or have children who are newly diagnosed, it’s important to be aware of and to understand the complex network of products, insurance providers, and nonprofits that are there to offer assistance. For many people, medical foods are a lifeline; doing without them isn’t an option. It’s also important to recognize and understand that not all products labeled as “medical foods” fall into the same category of need and to know the difference.

— Densie Webb, PhD, RD, is a freelance writer, editor, and industry consultant based in Austin, Texas.

References

1. US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. Frequently asked questions about medical foods; second edition — guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/GuidanceRegulation/

GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/UCM500094.pdf. Published May 2016.

2. Berry SA, Kenney MK, Harris KB, et al. Insurance coverage of medical foods for treatment of inherited metabolic disorders. Genet Med. 2013;15(12):978-982.

3. Therrell BL Jr, Lloyd-Puryear MA, Camp KM, Mann MY. Inborn errors of metabolism identified via newborn screening: ten-year incidence data and costs of nutritional interventions for research agenda planning. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;113(1-2):14-26.