September 2018 Issue

September 2018 Issue

CPE Monthly: Eating Disorders in the LGBTQ Population

By Vanessa Thornton, MS, CSP, RD

Today's Dietitian

Vol. 20, No. 9, P. 46

Suggested CDR Learning Codes: 1040, 3005, 3020, 5200

Suggested CDR Performance Indicators: 1.1.3, 1.3.6, 8.3.6, 10.1.2

CPE Level 2

Take this course and earn 2 CEUs on our Continuing Education Learning Library

The face of eating disorders is changing. Disorders including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder have long been associated with young, middle class, straight females, but health care providers are now seeing eating disorders across all ages, classes, and various sexual orientations and gender identities. The lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) community in particular recently has experienced a surge in diagnosed eating disorders. In fact, studies have shown that gay and bisexual men, adolescents who are unsure of their sexuality, and individuals who are attracted to more than one sex also are at heightened risk of disordered eating behaviors.1,2 Unfortunately, because past eating disorder research has focused so heavily on young, straight females, research and subsequent programming for prevention and treatment in the LGBTQ demographic is lacking.

Untreated, eating disorders can have serious consequences, including psychological and physical comorbidities and mortality. It's imperative that the health care community, including RDs, understands eating disorders through a wider lens of sexualities and genders to treat all individuals affected. This requires a deeper understanding of eating disorder pathology in these populations and the cultural competence to treat these individuals in a respectful and meaningful way.

This continuing education course examines the prevalence of and risk factors for disordered eating patterns in the LGBTQ community, the clinical implications of these behaviors, and strategies to help dietitians gain cultural competence and advocate for LGBTQ individuals at risk of eating disorders.

Prevalence in the LGBTQ Community

Eating disorders have long been a major worldwide health concern. In fact, they're considered the third most common childhood illness in the United States, surpassed only by obesity and asthma.3 Current research reveals an alarming rate of disordered eating in the LGBTQ community. One study found that LGBTQ youth were more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to report binge eating and purging starting as early as age 12 to 14 and persisting into adulthood.4 While it's clear that eating disorders are an issue in the LGBTQ community, it's important to note that the prevalence of various disordered eating behaviors differs across sexualities and gender identities.

Studies have shown that gay and bisexual men account for 14% to 42% of people with diagnosed eating disorders in this country, even though they make up less than 4% of the US population.5 A 2013 study by Austin and colleagues found that one in five gay and bisexual high school males reported disordered weight control behaviors (such as restricting, purging, and using diet pills), while only one in every 20 of their heterosexual male peers reported these behaviors.6

The prevalence of disordered eating in the lesbian community also is revealing. Early research suggested that self-identifying as lesbian was a protective factor against disordered eating. The theory was that perhaps lesbian women were less susceptible to social pressure to look a certain way than were straight women. More recent studies suggest that rates of body dissatisfaction and internalization of social pressure are similarly high among lesbian and heterosexual women.5 There also appear to be higher rates of binge eating and elevated BMIs in lesbian and bisexual women than in their heterosexual peers.6

Disordered eating in the transgender community is even less understood than that in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer/questioning communities, but the statistics so far are of concern. A 2015 survey by Diemer and colleagues focusing on college students found that transgender students reported the highest rates of diet pill and/or laxative use and more purging and previously diagnosed eating disorders than any other sexual or gender demographic. The prevalence in the transgender community was even higher than that of heterosexual females, which historically has been accepted as the highest-risk population for disordered eating.7

Risk Factors

These statistics demonstrate the need for awareness of and care for LGBTQ individuals with eating disorders. To accomplish this, dietitians must understand the potential triggers and risk factors for disordered eating patterns in these communities and appreciate that these may differ from more traditional triggers in young, straight female populations. It's well understood that body dissatisfaction, social pressures, and history of trauma or abuse are correlated with the development of eating disorders. But could there be more at play in LGBTQ individuals? The etiology of eating disorders in the LGBTQ community is just beginning to be understood. While some of the proposed triggers are similar to those associated with more traditional eating disorder patients, there are some important distinctions to be made.

Mental health plays a big role. It's well documented that, starting from youth, LGBTQ individuals are more likely to engage in risky behavior, have lower self-esteem, and battle depression and suicidal ideation.8 The Minority Stress Theory posits that stigmatized social groups, such as LGBTQ youth, experience excessive stress from discrimination, violence and bullying, social pressure, and alienation.9 Internalization of this stress is thought to negatively affect mental health, leading to low self-esteem and disordered thoughts and actions. Therefore, LGBTQ youth who aren't accepted in their communities and/or don't have adequate emotional and mental health support may be more susceptible to eating disorders.

Similar to traditional models of eating disorder causality, body image is thought to be a factor, but in a more dynamic way. Objectification theory is a social concept that's often used to explain the etiology of eating disorders in young, straight females. This theory explains the tendency for our culture to objectify female bodies and, in turn, pressure this population into modifying their bodies to meet social norms. Recent research, however, suggests that young females aren't the only population vulnerable to objectification.

Like young straight females, gay men also report placing importance on developing bodies that are pleasing to others. Traditionally, leanness is seen as the driving goal but, in this community, the desire for a muscular body is an additional force potentially leading to disordered eating behaviors. A study by Calzo and colleagues examined survey responses from 5,388 adolescent males and found 19% to 28% of respondents felt concerned about feeling lean and 18% to 21% of respondents felt concerned about feeling muscular, with more gay and bisexual males reporting concern for leanness than heterosexual participants. These concerns also were associated with more dieting, binge eating, and use of products such as creatine and steroids.10 It's not uncommon for young men to seek professional nutrition advice to build muscle. In light of recent research, dietitians should be aware of the potential for disordered and dangerous behaviors in these clients and screen for eating disorders accordingly.

The relationship between disordered eating and body image in the lesbian demographic is unique, and studies demonstrate conflicting results. Some suggest that self-identified lesbians are less concerned with body image and thinness than are their heterosexual peers. Others found similar rates of body dissatisfaction among gay and straight women, with higher likelihood to internalize social pressure in females (gay or straight) than in men, the difference being that lesbian and bisexual women may desire thinness or muscularity and masculinity.11 Research is limited, but suggests some lesbians desire to appear "authentic," or muscular, more than they desire to be thin. It's been proposed that this difference in ideal body image may be related less to body dissatisfaction and more to a desire for social identity and a rejection of heteronormative standards.12 Rates of higher BMIs, qualifying as overweight or obese, also tend to be higher in the lesbian population than in heterosexual females.5 This difference may result in less restrictive eating patterns than in women who desire thinness, but doesn't imply that other disordered eating behaviors aren't being used. In fact, bisexuals and lesbians are more likely to report binge eating than are self-identifying straight females.4

The high prevalence of disordered eating in the transgender community isn't so surprising in light of minority stress and body image issues as primary causes for disordered eating patterns. The transgender population, like gay, lesbian and bisexual groups, is under minority stress from social stigmatization. Transgender people also have a sense of gender dysphoria, or the feeling that there's a conflict between one's physical body and the gender with which they mentally and emotionally associate. Some transgender people will alter their bodies cosmetically, surgically, and/or hormonally to correct this feeling. Gender dysphoria may, however, also lead to body dysmorphia and result in disordered behaviors in an attempt to manipulate the body. Body dysmorphia is a separate concept commonly associated with eating disorders; it describes people who dwell on real or perceived flaws of their bodies. Disordered manipulations could involve rapid or excessive weight gain or loss or hyperfocus on muscularity, depending on the individual's gender identity and goals.

Across all gender and sexual minorities, there are common triggers that may lead to disordered eating behaviors, including low self-esteem, poor mental health, and body dissatisfaction. Dietitians shouldn't presume disordered eating based on a client's gender or sexual identity. Instead, dietitians need to become more culturally and clinically competent in working with the LGBTQ community to increase awareness, prevention, and intervention for this vulnerable population.

Cultural Competence

When working with any cultural group, the most important thing health care providers can do is gain a better understanding of the unique beliefs, ideals, and practices of the population and use this knowledge to create an open, comfortable space for patients. Cultural competence with regard to sexual and gender minorities is no exception but can be difficult, as a client's sexual orientation or gender identity isn't always known upon first encounter. Dietitians should be careful not to stereotype or assume, but should instead provide the best treatment based on the information the client is willing to share. In one survey of adolescents at a youth empowerment conference, Meckler and colleagues found that adolescents who had discussed sexuality and gender with a health care provider were those who had pediatricians with whom they felt a sense of familiarity and trust.13 Unfortunately, questions regarding sexuality and gender often aren't asked in health care settings. Providers often cite discomfort, lack of knowledge, or fear of insulting clients as reasons for not broaching the subject.14 This is despite official recommendations from organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics to discuss sexuality and gender identity with all adolescents.8 In fact, several professional organizations have released policies and guidelines to help health care professionals working with LGBTQ youth. Many of these guidelines apply to dietitians (see sidebar "Recommendations for Care").8,15

In a 2009 internet-based survey by Hoffman and colleagues, LGBTQ youth aged 13 to 21 in the United States and Canada were asked to rank a list of qualities they found important in health care providers. Respondents ranked equal treatment of LGBTQ youth as one of the most important qualities alongside competence, respect, and honesty. In fact, youth ranked many interpersonal skills as equally or more important than clinical competencies.16 A foundation of trust is of utmost importance when treating this population. Furthermore, study participants indicated that some of the most important health concerns they'd like to discuss with providers include preventive health care, depression/suicidal ideation, and nutrition.16

Clearly, the expertise of dietitians is an important asset in the prevention and treatment of LGBTQ eating disorders. Dietitians can demonstrate cultural competence using visual and verbal cues. Visually, providers should ensure gender-neutral messaging in all details, from the magazines offered in the waiting room to the design of handouts, brochures, etc. Hanging an LGBTQ-friendly poster or symbol in the office also can help patients feel more comfortable discussing their gender, sexuality, and related health care problems. Intake forms shouldn't presume heterosexual orientation or binary (male/female) gender status. Office spaces should offer gender-neutral bathrooms if possible.

Verbal cues to demonstrate knowledge and understanding of LGBTQ populations also are crucial to creating a safe space. Avoiding presumptive language and using appropriate vocabulary helps LGBTQ individuals feel more comfortable. For example, instead of asking, "Do you have a boyfriend? Is he supportive?" ask, "Do you have a supportive partner?" or simply, "Tell me about your support system." While providers may fear offending individuals by broaching the subject, research shows this fear is unwarranted. For example, when Meckler and colleagues surveyed 140 teens asking what could be done to make talking to health care providers about sexuality and gender identity more comfortable, 64% of participants responded, "Just ask me."13 Offering patients the opportunity to disclose this information in a respectful way can help build a foundation of trust and lead to important conversations that help dietitians understand potential risk factors for eating disorders or uncover unsafe food behaviors.

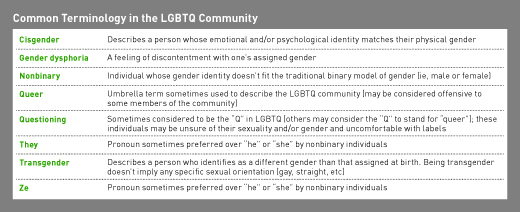

It's also important for dietitians to become familiar with and feel comfortable using preferred terminology for various sexual preferences and genders. This is especially important in the transgender community, where individuals may go by a different name than that listed on the medical record or prefer pronouns other than "he" or "she." By "just asking," dietitians can demonstrate cultural competence and create a more positive experience for patients. The table on page 49 lists some common terms used within the community.8,15,16

The National LGBT Health Education Center has some excellent resources to create LGBTQ-friendly practices. It recommends asking for patients' names and preferred pronouns regularly. It also assures providers that making mistakes in addressing patients is a natural part of gaining competence and encourages them to be open, apologize for mistakes, and use these incidents as opportunities to learn from their patients, reinforcing respect and the desire to get it right.15

Dietitians and other health care providers shouldn't presume the sexual orientation or gender identity of any patient. They shouldn't reserve these discussions for only those they suspect not to be heterosexual gender-binary individuals, as this can lead to stereotyping. While research has shown a distinct prevalence of eating disorders in this population, it's also important to not assume disordered eating or other risky behaviors are present in all patients who identify as part of the LGBTQ community. Finally, in the American Academy of Pediatrics 2013 Policy Statement on caring for LGBTQ youth, it's also noted that providers who don't feel comfortable or competent treating this population can offer the best care by referring its members to providers who are culturally competent.8

Clinical Implications

Dietitians in ambulatory or private care settings often are asked to help screen patients for potential eating disorders. There are several validated tools that are widely used for this purpose. Some, such as the Eating Disorder Inventory, are self-reported surveys, while others, such as the SCOFF Questionnaire (acronym based on questions in the survey), are administered by clinicians. It's important to note, however, that these tools were created and validated largely for the straight female population and may not be an accurate assessment in sexual and gender identity minorities.17 For example, a tool may ask whether clients feel their legs are too fat. While this may capture body dysmorphia for those who value thinness, it doesn't capture those who may instead strive for muscularity or masculinity. There's a current call for expanded validation of these tools in the LGBTQ population and the creation of specific tools for sexuality and gender identity minorities. The Eating Disorder Assessment for Men tool was created in 2012 to screen for disordered behaviors in males, which may better capture a drive for muscularity vs thinness and behaviors seen more often in male eating disorder patients, such as inappropriate use of steroids, protein supplements, and/or exercise. Future research should focus on expanded tools to meet the unique screening needs of other subpopulations such as the transgender community.

Once disordered eating is identified, the dietitian must keep in mind some important clinical considerations specific to the LGBTQ community. The practices of these individuals may vary from those thought to be typical of eating disorders, and the nutrition implications are important. One of these differences is physical activity. There's a disparity in the amount of physical activity and team sport participation in LGBTQ vs heterosexual, gender-binary (male or female) youth. A 2014 study showed that LGBTQ youth aged 12 to 22 reported 1.21 to 2.62 fewer hours per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity. They also were 46% to 76% less likely to participate in team sports.18 It's well known that physical activity is important to protect against overweight/obesity, stress, and depression—all of which may in turn lead to disordered eating patterns. This lack of physical activity also may increase risk of diabetes and CVD. It's important to consider that LGBTQ youth may have what Calzo and colleagues refer to as a lower "athletic self-esteem," or a feeling of physical or athletic incompetence. They also may fear social stigma, bullying, or drawing attention to their bodies.18 Dietitians should approach these issues with empathy and be prepared to help individuals find modes of physical activity they find enjoyable and comfortable.

The drive for muscularity in some gay men, lesbians, and other LGBTQ individuals may lead to use of steroids and creatine and excessive intake of protein supplements. Improper use may lead to dyslipidemia, mood disorders, aggressive behavior, gynecomastia, amenorrhea, and liver or renal complications.19 All of these symptoms may be exacerbated by additional disordered eating behaviors, including restricting, binging, and purging. Dietitians should always inquire about supplementation and dosing when treating patients at risk of eating disorders.

As previously discussed, many women of any sexual orientation are driven by social pressure to be thin. Some lesbians and bisexual women who are overweight or obese, however, may prefer this body shape and might not be motivated to lose weight for the sake of improving body image or satisfaction. Instead, dietitians should focus on the health benefits of weight loss and binge eating control, increased athletic ability, and decreased risk of diabetes, CVD, and other comorbidities. Dietitians also may need to accept that the calculated ideal BMI may not be the same as the patient's perceived ideal BMI and reconcile these differences.

Transgender patients may opt for surgical intervention, hormone therapy, or both. An emerging body of research shows that these treatments may affect risk of certain comorbidities and, in turn, MNT indications. While data still are limited, there's some indication that male-to-female transgender women may be at increased risk of cardiovascular conditions. One study found that 6% of transgender women had cardiovascular issues after 11.3 years on estrogen therapy.20 Hormone therapy also seems to be associated with increased insulin resistance, fasting glucose levels, and subcutaneous fat in transgender women. Transgender men on hormone therapy also were found to have increased insulin resistance and visceral fat stores. Type 2 diabetes seems to be more prevalent in the transgender population, though it's unclear whether this is related to surgical or hormonal interventions. Osteoporosis and low bone mass also are reported in transgender women, even those who haven't undergone any gender reassignment therapies. This may be related to low levels of physical activity and vitamin D deficiency in this population, both of which can be addressed and prevented with nutrition intervention.20

To the best of this author's knowledge, there's no current research examining change in energy needs for transgender patients who have undergone hormone and/or surgical therapies. Given what's known about metabolism and body composition, it's probable that changing the body's hormone levels and amount of visceral body fat may alter the individual's energy needs. Future research should be conducted to examine this relationship to provide more appropriate care and accurate MNT goals.

All of these comorbidities are especially important to consider in eating disorder patients, as their disordered practices may amplify these risks. Anorexia nervosa is associated with cardiovascular risk and osteopenia, while binge eating disorder is associated with development of type 2 diabetes. Dietitians always should remain aware of these risks and provide MNT accordingly.

Putting It Into Practice

For those RDs working in ambulatory and private practice settings, cultural and clinical competencies in working with LGBTQ individuals are imperative to better serve this at-risk population. Eating disorders are best treated with a multidisciplinary team including, at minimum, a medical doctor, dietitian, and mental health professional. To best serve patients, dietitians should connect with providers who also are comfortable and competent working with LGBTQ individuals to create care teams and referrals to professionals who can provide compassionate and thoughtful care. This includes primary care providers, psychologists, and psychiatrists.

Connecting LGBTQ individuals with eating disorders to each other is another potentially effective mode of prevention and treatment in this population. Group work often is considered a useful component in both traditional models of eating disorder treatment and in the LGBTQ community for support and advocacy efforts. Groups create a sense of community, help individuals feel less isolated, and potentially encourage eating disorder patients to help each other through recovery. While many communities offer some form of eating disorder support groups, there are few tailored specifically to the LGBTQ community. Creating such groups is an excellent opportunity for dietitians to spearhead advocacy efforts in their communities and provide nutrition expertise.

In 2016, the Healthy Weight in Lesbian and Bisexual Women study offered physical activity and nutrition programming for 12 to 16 weeks in 10 cities across the United States targeted specifically to self-identifying lesbian and bisexual women. The programs focused not on weight loss but instead on helping participants feel more healthful and become more active, all while providing the comfort and community of lesbian and bisexual women-based groups. An impressive 95% of participants were able to meet at least one of the following six goals: increasing fruit and vegetable consumption, decreasing sugary beverage intake, decreasing alcohol intake, increasing physical activity, improving quality of life, and decreasing weight, waist circumference-to-height ratio, and/or body size.21

Direct patient care isn't the only way for dietitians to advocate for LGBTQ individuals. Community dietitians also can contribute and advocate for LGBTQ individuals by creating more targeted eating disorder awareness and prevention campaigns. Teachers, parents, coaches, and other health care providers can benefit from more education and awareness of this population and the heightened risks of disordered eating behaviors. Dietitians can advocate by getting involved with policy making and lobbying for LGBTQ rights in the health care system. There's also a need for more research on these topics. Dietitians play a central role in the treatment of eating disorders and should be involved in future projects regarding best screening, prevention, and treatment options, including more evidenced-based clinical guidelines in LGBTQ populations.

— Vanessa Thornton, MS, CSP, RD, is a Boston-based pediatric dietitian working with children and adolescents with eating disorders.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CARE

- Create intake forms that don't assume gender/sexual identity.

- Train office staff to avoid presuming heterosexuality of patients.

- Post LGBTQ-friendly signage, brochures, and reading material in your waiting room.

- Deliver a message of acceptance of all sexual orientations and gender identities.

- Provide additional education and referrals for transgender individuals to show increased support.

- Create community groups and support advocacy efforts.

- Educate yourself about local and national resources for LGBTQ clients.

- Refer to competent providers if you're uncomfortable counseling LGBTQ patients.

Learning Objectives

After completing this continuing education course, nutrition professionals should be better able to:

1. Evaluate the risk factors for and prevalence of eating disorders in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) population.

2. Assess how various sexual orientations and gender identities influence body image perception.

3. Employ preferred terminology and vocabulary used in the LGBTQ community.

4. Adopt at least two strategies to create a safe space for LGBTQ individuals.

CPE Monthly Examination

1. Based on a 2013 study, how many gay and bisexual high school males reported disordered eating behaviors?

a. One in every two

b. One in every five

c. One in every 20

d. One in every 100

2. Which theory helps explain some of the social pressure lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) individuals experience that may lead to eating disorders?

a. Minority stress theory

b. Objectification theory

c. Gender identity theory

d. Stigmatization theory

3. The desire for thinness often is associated with eating disorders. According to this article, desire for which of these other body image ideals may influence gay men to engage in disordered eating behaviors?

a. Desire to be taller

b. Desire to be more muscular

c. Desire for smaller waists

d. Desire for a more feminine figure

4. You meet a client named "Sam" who did not check "male" or "female" on the intake form. How might you approach this individual in a respectful way?

a. Ask which pronouns Sam prefers to use.

b. Avoid using pronouns such as "he" or "she" to avoid offending the client.

c. Listen to the pronouns Sam uses during the visit and try to use the same.

d. Ask whether Sam identifies as male or female.

5. Which of the following is an example of a visual cue that can be used to create an LGBTQ-friendly space?

a. Avoid displaying any photos or images of heterosexual individuals or couples.

b. Post an LGBTQ "safe space" sticker on your door.

c. Provide patients whom you think might be gay with pamphlets containing images of homosexual couples.

d. Don't offer any magazines or reading material in the waiting room to avoid offending anyone.

6. Which of the following is a disordered body manipulation behavior males may be more likely to engage in?

a. Steroid or supplement abuse

b. Restrictive eating pattern

c. Laxative abuse

d. Excessive cardiovascular exercise

7. Which of the following is an example of cultural competence with respect to the LGBTQ community?

a. Asking feminine-looking males about their partners instead of girlfriends or wives

b. Using the pronoun "ze" for all transgender patients

c. Avoiding discussion of gender and sexuality with patients so as not to offend them

d. Creating intake forms that ask all patients about sexual orientation and preferred pronouns

8. A 2015 study by Diemer and colleagues suggests that the prevalence of disordered eating behaviors is highest in which demographic?

a. Straight females

b. Gay males

c. Transgender individuals

d. Bisexual females

9. Which of the following is an eating disorder tool validated for gay and straight men?

a. SCOFF Questionnaire

b. Eating Disorder Inventory

c. The Eating Disorder Assessment for Men

d. Eating Disorder Questionnaire

10. Transgender patients may use disordered eating patterns in an attempt to change their bodies to look more masculine or feminine. Which of these concepts explains this desire?

a. Body dysmorphia

b. Gender dysphoria

c. Questioning

d. Gender confusion

References

1. Feldman MB, Meyer IH. Eating disorders in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(3):218-226.

2. Shearer A, Russon J, Herres J, Atte T, Kodish T, Diamond G. The relationship between disordered eating and sexuality amongst adolescents and young adults. Eat Behav. 2015;19:115-119.

3. Croll J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M. Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: relationship to gender and ethnicity. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(2):166-175.

4. Austin S, Ziyadeh N, Corliss H, et al. Sexual orientation disparities in purging and binge eating from early to late adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(3):238-245.

5. Yean C, Benau, E, Dakanalis A, Hormes J, Perone J, Timko CA. The relationship of sex and sexual orientation to self-esteem, body shape satisfaction, and eating disorder symptomatology. Front Psychol. 2013;4:887.

6. Austin S, Nelson A, Birkett M, Calzo J, Everett B. Eating disorder symptoms and obesity at the intersections of gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation in US high school students. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):e16-e22.

7. Diemer E, Grant J, Munn-Chernoff M, Patterson D, Duncan A. Gender identity, sexual orientation, and eating-related pathology in a national sample of college students. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(2):144-149.

8. Committee on Adolescence. Office-based care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):198-203.

9. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674-697.

10. Calzo J, Masyn K, Corliss H, Scherer E, Field A, Austin S. Patterns of body image concerns and disordered weight-and-shape related behaviors in heterosexual and sexual minority adolescent males. Dev Psychol. 2015;51(9):1216-1225.

11. Morrison M, Morrison T, Sager C. Does body satisfaction differ between gay men and lesbian women and heterosexual men and women? A meta-analytic review. Body Image. 2004;1:127-138.

12. Levitt H, Hiestand K. Gender within lesbian sexuality: butch and femme perspectives. J Constr Psychol. 2005;18(1):39-51.

13. Meckler GD, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Beals KP, Schuster MA. Nondisclosure of sexual orientation to a physician among a sample of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(12):1248-1254.

14. Remafedi G. Adolescent homosexuality: dare we ask the question? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(12):1303-1304.

15. Providing affirmative care for patients with non-binary gender identities. The National LGBT Health Education Center website. https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/publication/providing-affirmative-care-patients-non-binary-gender-identities/. Published 2017.

16. Hoffman N, Freeman K, Swann S. Healthcare preferences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning youth. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:222-229.

17. Floyd S, Pierce D, Geraci S. Preventive and primary care for lesbian, gay and bisexual patients. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352(6):637-643.

18. Calzo J, Roberts A, Corliss H, Blood E, Kroshus E, Bry Austin S. Physical activity disparities in heterosexual and sexual minority youth ages 12-22 years old: roles of childhood gender nonconformity and athletic self-esteem. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47(1):17-27.

19. Snyder PJ. Use of androgens and other hormones by athletes. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/use-of-androgens-and-other-hormones-by-athletes. Updated December 4, 2017.

20. Feldman J, Brown GR, Deutsch MB, et al. Priorities for transgender medical and healthcare research. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(2):180-187.

21. McElroy JA, Haynes SG, Eliason MJ, et al. Healthy weight in lesbian and bisexual women aged 40 and older: an effective intervention in 10 cities using tailored approaches. Womens Health Issues. 2016;26(Suppl 1):S18-S35.