By Karen Meadows, MA, MS, CDE

Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 15 No. 5 P. 20

Americans with type 1 diabetes are Supreme Court justices, Olympic champions, and professional actors and musicians. As a result, travel is part of their lives. But some people with type 1 diabetes (or their families) are apprehensive about traveling with their condition, especially on long trips away from home. The good news is that dietitians can effectively address these patients’ fears and encourage them to safely venture out.

Imagine Allison, a 17-year-old patient with type 1 diabetes who wants to visit the Grand Canyon and participate in various activities while there. Anticipating a river rafting trip, she’s improved her self-care and is using an insulin pump and a continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS). Allison’s endocrinologist says to let her go on the trip, but her parents think the trip is too dangerous, wondering how Allison will keep her insulin cold and her pump dry, and what will happen if her glucose goes too high or too low.

Matt, 40, has adult-onset type 1 diabetes and hasn’t traveled since his diagnosis. He hopes to attend his family reunion in Pennsylvania Dutch country. He feels confident about administering the right amount of insulin to normalize his blood glucose after meals and snacks, but he lacks willpower when faced with tempting high-carbohydrate foods. Matt knows he’ll overindulge on shoofly pie and schnitz un knepp (dried apples and ham with dumplings). Plus, he’s worried about airport security and the possibility of being searched. His stress increases his blood glucose level.

Both Allison’s parents and Matt assume there are limits to traveling when someone has type 1 diabetes, but dietitians can successfully address these assumptions. Whether patients with diabetes want to hike, scuba dive, or ride the rapids, they can travel safely and securely anywhere and enjoy life just as much as anyone who doesn’t have the disease.

Dispelling the Myths

The most common concerns and misconceptions about traveling with type 1 diabetes include insulin use and storage, availability of medical help, and dining out. Consider the following:

• Myth: Insulin must be refrigerated. Insulin that’s been opened must be kept cool and out of direct sunlight but doesn’t need to be refrigerated. Instructions for insulin pens specifically state that pens in use should be kept at room temperature. Travelers with type 1 diabetes can wrap insulin vials or pens in a sweater or jacket, bury them in a backpack or bag, and keep them in the shade. In extreme temperatures, injectables can be stored in insulated carriers designed for lunches, camping, or diabetic supplies.

• Myth: Don’t stray far from medical help. Everyone is at risk for accidents or equipment failures when traveling; type 1 diabetes patients simply need to be better prepared. Optimally, they should have a medical team on call 24/7, but that isn’t always possible.

For instance, Allison would be isolated in the Grand Canyon, but since she’s established good control, uses a CGMS, has knowledgeable friends, and tends to follow a plan her dietitian helped her develop, she minimizes her risks. Allison can keep her insulin pump dry with a waterproof case that she can wear under her life vest and can disconnect the pump to swim. She should carry both rapid- and long-acting insulin in pens or vials (with syringes) to replace the pump if necessary.

• Myth: Eating away from home is too difficult. Dining out and eating local and seasonal specialties is a traveling pleasure. The key for type 1 diabetes patients is to know their insulin-to-carbohydrate ratios, target carb intake for snacks and meals, and know which foods won’t raise blood glucose. In Matt’s case, a dietitian could suggest he balance pie and dumplings with low-carb choices such as heirloom tomatoes and farmers’ cheese.

Additionally, national chain restaurants post menus and carbohydrate content online and at each location. For patients with smartphones, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) lists free nutrition apps in its annual consumer guide, which could help with finding nutritional information necessary for dining out.

Airport Security

The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) asks travelers with diabetes to inform airport security personnel when they have medical supplies or equipment to be scanned and if they’re wearing insulin pumps. The TSA and the ADA provide air travel guidelines on their respective websites.

Type 1 diabetes patients can send insulin, syringes, pens, and meters through scanners. Some insulin pumps can pass through metal detectors but not X-ray machines. Patients whose pumps can’t go through the X-ray scanners likely will be patted down and have their hands and pumps swabbed for explosives. Patients should be advised to stay calm during the process and allow extra time to get through security.

Once dietitians address their patients’ fears, they should evaluate their patients’ overall self-care and coping skills, and then help them to develop strategies.

Blood Sugar

Type 1 diabetes patients are always at risk of blood sugar highs and lows that may require medical attention. Exceptional highs may lead to diabetic ketoacidosis, and dangerous lows may lead to erratic behavior or unconsciousness. Changes in food intake, time zones, sleep patterns, or physical activity all affect blood sugar.

“The No. 1 rule for safe travel is to check your glucose levels frequently and to always be prepared to treat with extra food or insulin,” says Francine Kaufman, MD, author of Insulin Pumps and Continuous Glucose Monitoring, which includes a chapter on planning specifics for domestic and international travel.

It’s important for dietitians to challenge their type 1 diabetes patients to check their glucose levels quickly and accurately anytime, anywhere. Dietitians should help patients identify symptoms of high and low blood sugar, and learn how to remedy both quickly.

Patients will need to check for ketones when their glucose is 240 mg/dL or higher, especially when they experience symptoms such as nausea or vomiting. Some glucose meters check blood ketones. Otherwise, travelers can carry individually wrapped urine ketone strips. If testing indicates moderate-to-large ketone levels, patients should call their physicians or go to an emergency department. High ketone levels indicate the onset of diabetic ketoacidosis, which is life threatening.

Patients whose glucose is tightly controlled may need a reminder that overcorrecting highs can lead to lows. For low blood sugar, patients should know the “Rule of 15”: When feeling low, test glucose. If lower than 70 mg/dL, eat or drink 15 g of simple carbohydrate. Wait 15 minutes. Test again. Repeat if necessary.

Adjusting Insulin

Patients can address blood sugar highs with individualized insulin correction doses. To learn more about this, dietitians can use the Johns Hopkins diabetes guide Nutrition for Type 1 Diabetes as a resource. The guide provides basic recommendations for correctional dosing, establishing insulin-to-carbohydrate ratios, and meal planning.

Patients may need to modify both basal and bolus insulin rates when traveling. If insulin adjustments aren’t your area of expertise, refer clients to an endocrinologist or a CDE specializing in insulin management.

Emergencies

It’s important to know that true emergencies are rare and best addressed by a patient’s medical team. However, patients should expect the unexpected and know how to respond. They should be advised to train fellow travelers to recognize symptoms of hypo- and hyperglycemia and provide support. Informed fellow travelers should be able to check glucose and administer glucagon, especially in cases of hypoglycemia unawareness.

In addition, dietitians should urge patients to ensure medical supplies, such as insulin pens and vials, aren’t expired or won’t expire on their trip. Newer insulin users will need to know how long opened insulin pens and vials last. Nevertheless, no matter how well travelers prepare, sometimes things happen that are out of their control (eg, plane delays, storms, flat tires, stranded cruise ships), so patients should keep extra food with them at all times, such as packing energy bars to serve as snacks or meals if needed.

Medical Supplies

When traveling, patients should take double the medications and supplies they’ll need and hand-carry them on public transportation. My friend with type 1 diabetes went to Mexico and had her purse stolen, which contained her insulin and glucose meter. She and her friends drove to the nearest medical clinic, where she was offered an injection from a half-full bottle of regular insulin. She took that shot and went to a city where she could buy insulin and supplies. Her life could have been in jeopardy.

To avoid a similar situation, type 1 diabetes patients should keep their necessary medical gear in at least two locations when traveling, so if something is stolen or lost they have a backup.

With your guidance, patients with type 1 diabetes can travel safely and with confidence. Comprehensive planning will free them to enter a world of discovery and fully enjoy their lives.

— Karen Meadows, MA, MS, CDE, is a freelance writer living in New Mexico who has type 1 diabetes. She writes and speaks about living dynamically with diabetes and enjoys traveling domestically and abroad.

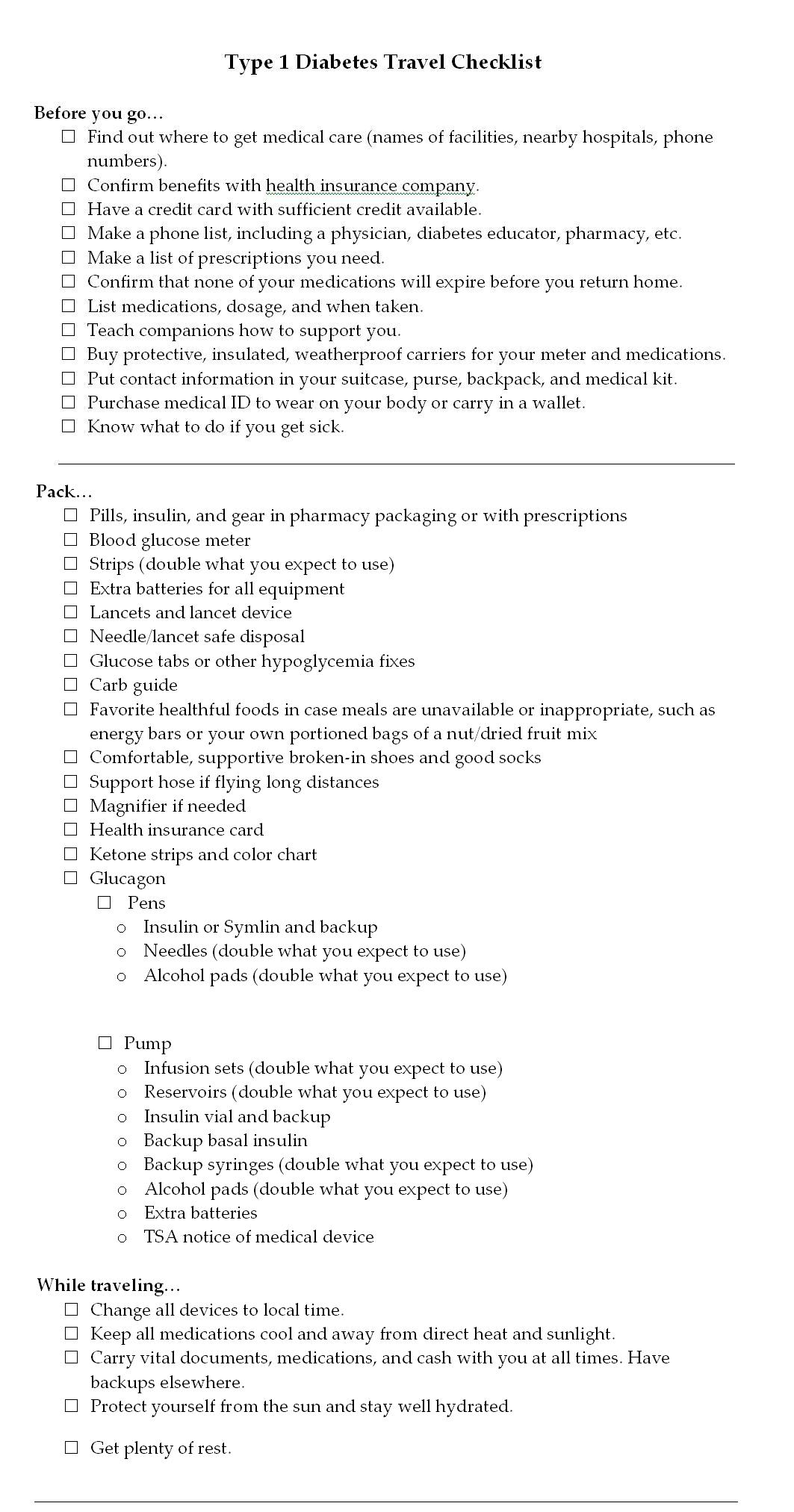

Type 1 Diabetes Travel Checklist

(click to enlarge)

Resources

- American Diabetes Association travel fact sheet (www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/treatment-and-care/medication/when-you-travel.html)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention travel tips (www.cdc.gov/Features/Diabetes

AndTravel) - Transportation Security Administration guidelines (www.tsa.gov)