Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 19, No. 3, P. 40

The Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children has been around for decades and continues to further improve the nutrition and health status of those who participate.

WIC has come a long way. It began as a pilot program in 1972, when doctors expressed to Congress that they were seeing an increasing number of low-income mothers presenting with health issues related to nutrient deficiencies. In 1975, WIC became a permanent federal program designed to supplement the diets of at-risk individuals, including pregnant and postpartum mothers and their infants and young children.1

WIC’s mission has remained the same since its founding: to safeguard the health of low-income women, infants, and children up to age 5 who are at nutritional risk. However, the program’s goals have expanded to also include promoting and supporting successful long-term breast-feeding; providing WIC participants with a wider variety of foods, including fruits, vegetables, and whole grains; and giving WIC state agencies greater flexibility in prescribing food packages to accommodate cultural food preferences of WIC participants.1

Administered by the US Department of Health and Human Services, WIC currently is funded under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 and is the third largest federal nutrition assistance program after the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the National School Lunch Program. Funds are distributed to 1,900 WIC agencies, which manage the program on the local level at more than 10,000 clinic sites across the United States. WIC isn’t an entitlement program; that is, it doesn’t guarantee assistance for all qualifying applicants. However, some states match or contribute to WIC funding to help cover the greatest number of individuals possible. Applicants who don’t receive benefits immediately are placed on a waiting list that gives priority to those with serious health conditions such as anemia, underweight, and who have a history of pregnancy complications.1

Eligibility Requirements

WIC is a complex program that aims to “supply specific types of foods and other benefits to a highly targeted group of participants” who must meet several eligibility requirements.2 To be eligible for WIC, applicants must meet categorical, residential, income, and nutritional requirements.

Categorical eligibility specifies that an individual must be pregnant, a breast-feeding mother up to one year postpartum, a nonbreast-feeding mother up to six months postpartum, an infant up to age 1, or a child up to age 5. Residential rules specify that applicants must reside in the state in which they apply for benefits. Income eligibility in all states currently requires applicants to demonstrate a family income below 185% of the federal poverty level, which in 2014 was around $44,123 for a family of four.1 Individuals who can demonstrate eligibility for SNAP, Medicaid, or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families also are considered eligible for WIC.

In addition, clients must meet nutrition risk requirements as determined by a physician, nurse, or nutritionist. The health care provider must document an applicant’s height and weight, results of a blood test for anemia (except for infants under 9 months), and gather medical history and dietary pattern information. These data are then used to determine the type of nutrition package, nutrition education, and health referrals the client will receive.

Nutrition risk is defined as a medically based or dietary-based condition. Examples of medically based conditions include anemia, underweight, maternal age, history of pregnancy complications, or poor pregnancy outcomes. Types of dietary risk include the following1,3:

• detrimental or abnormal nutritional conditions detectable by biochemical or anthropometric measurements such as anemia, underweight, or overweight;

• other documented nutritionally related medical conditions such as nutrient deficiency diseases, metabolic disorders, or lead poisoning;

• dietary deficiencies that impair or endanger health such as inadequate dietary patterns;

• conditions that directly affect the nutritional health of a person, including alcoholism or drug abuse; or

• conditions that predispose people to inadequate nutritional patterns or nutritionally related medical conditions, including, but not limited to, homelessness and migrancy.3

Recertification of participants is required in order to renew benefits. However, the end goal is to “graduate” participants from the program when they’re able to meet their own nutritional needs adequately. A typical certification for WIC benefits lasts six months, but this varies by participant type. Pregnant women are certified for the duration of their pregnancies and up to six months postpartum. Many state agencies allow infants, children, and breast-feeding women a one-year certification period as well.2 Recertification is required so participants can continue receiving benefits.

WIC Benefits

WIC provides three types of benefits: food packages, nutrition education, and health care and social service referrals. Benefits are provided in communities at accessible public sites such as county health departments, schools, community centers, mobile clinics, public housing sites, migrant health centers, and Indian Health Service facilities.1

WIC Food Packages

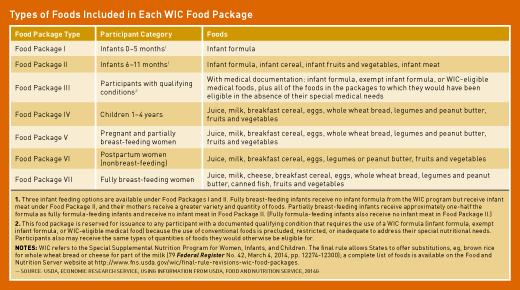

As the cornerstone of the WIC program and its biggest expenditure (about 70% of total WIC costs), food packages are provided to help supplement participants’ grocery purchases. Today, cash value vouchers, which offer clients choice and flexibility in their purchases, have replaced the older vouchers that specified certain quantities of certain foods (eg, one dozen eggs). However, today’s vouchers limit purchases to nutritious foods that help meet clients’ specific nutrient needs. Some states already have introduced electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards that take the place of paper vouchers. The implementation and use of EBT cards will be required for all state WIC agencies beginning October 1, 2020.2

In 2007–2009, WIC revised its food packages, representing the most important nutritional change to WIC in many years. Whole wheat bread was added to most food packages, and juice was eliminated from infant food packages. Milk was restricted to nonfat for individuals over age 1, and the quantity of milk that can be replaced by cheese was reduced. A greater number of permitted alternative foods (eg, soymilk and tofu for milk, brown rice or soft corn tortillas for whole wheat bread) was increased.1

Clients receive food packages based on dietary needs, not income. The monetary values of the packages vary widely, with infant formula accounting for 42% of total food costs, followed by milk at 14% of costs, and then fruits and vegetables at 10%.2

By law, the USDA must review and update the contents of WIC food packages at least every 10 years to ensure their compliance with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The USDA asked the Institute of Medicine to complete the most recent evaluation, which is still in progress. In February 2015, a report on the first phase of the evaluation was released. According to the food package evaluation committee in its interim report, “WIC Food Packages: Proposed Framework for Revisions: Interim Report,” a key outcome of Phase I was that white potatoes, which had been excluded from the cash value vouchers as a food option in 2009, were added back to the list of allowable foods. The Phase I report also identified several nutrients that are inadequate in the diets of many WIC participants and therefore should be the focus of WIC’s food package revisions.4

Reviews of the current food packages, compared with purchases made during the time of WIC’s previous food packages, suggest that WIC households are purchasing smaller amounts of juice, whole milk, and cheese, and higher amounts of lower-fat milk, whole grains, fruits, and vegetables than before the food package changes.2 Spaulding and colleagues, in their February 2014 USDA report, “Using the National Food and Nutrition Survey (NATFAN) to Examine WIC Participant Food Choices and Intakes Before and After Changes in the Food Packages,” reported that participants also seem to be purchasing more fruit drinks and noncarbonated beverages, and fewer soft drinks.

Nutrition Education and Breast-Feeding Promotion

Nutrition education isn’t a requirement for WIC clients to receive benefits; however, WIC agencies are required to offer nutrition education sessions to participants on a quarterly basis. Nutrition education can be provided to individuals or groups in person or through online modules. WIC nutrition education has several broad goals: to emphasize the links between nutrition, physical activity, and health; raise awareness about the dangers of drug use; and assist participants at nutritional risk in improving their health status through diet and the use of supplemental foods.2

Breast-feeding promotion is one of the key counseling services at WIC. States require WIC agencies to spend an amount that’s equal to at least one-sixth of the cost for nutrition services and administration on breast-feeding.1,2 All pregnant participants are encouraged to breast-feed (unless medically contraindicated) under WIC’s peer educator-based program “Loving Support.” Peer educators are hired from WIC’s own population to teach, support, and follow up with mothers learning to breast-feed. Cultural competence is necessary for delivering nutrition education to tailor information and delivery to the needs of specific individuals and populations.1,2

WIC Outcomes

The USDA says that “WIC saves lives and improves the health of nutritionally at-risk women, infants, and children.”1 Several studies on WIC outcomes show that the program is one of the nation’s most impactful and cost-effective nutrition assistance programs.1 Data from the National Maternal and Infant Health Survey show that WIC improves birth outcomes and helps contain health care costs by helping to support longer pregnancies, fewer premature births, healthy birth weights, lower infant mortality, and better prenatal care.1

Surveys of WIC participants in California, New England, and New York before and after the implementation of the 2009 food packages show that there have been increases in fruit, vegetable, whole grain, and lower-fat milk consumption among all WIC participants.5 WIC’s breast-feeding promotion program has narrowed the gap between breast-feeding rates of WIC and non-WIC mothers. The USDA study “WIC Participant and Program Characteristics, 2012” by Johnson and colleagues of Insight Policy Research showed that the percentage of breast-fed infants enrolled in WIC has increased from 44.5% in 2000 to 67.1% in 2012. “Vital Signs: Obesity Among Low-Income, Preschool-Age Children, 2008–2011,” published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on August 9, 2013, suggests that federal policy reforms in child nutrition programs, including changes to WIC food packages, may have contributed to the leveling off of childhood obesity rates among low-income preschool children. Research shows that WIC has helped to reduce rates of childhood anemia.5 Children enrolled in WIC also seem to have higher mean intakes of iron, vitamin C, thiamin, niacin, and vitamin B6, without having diets higher in total energy than non-WIC children.2 WIC also has helped lower rates of iron deficiency anemia from 7.8% in 1975 to 2.9% in 1985.5

Opportunities for RDs

There are many available positions that require RDs’ expertise in WIC agencies and clinics across the nation. Director, nutritionist, and breast-feeding coordinator are some of the positions that put dietitians in charge of working with participants or managing people and programs at WIC sites.

WIC populations, including participants’ cultural food preferences, feeding practices, and feeding styles, are areas that require further research, which would enable policymakers to make decisions about future WIC food packages and programming. There’s also a dearth of research on participant satisfaction with the current food packages and on how packages affect how parents feed their young children.4 The Institute of Medicine reported that knowledge of behavioral economics strategies might be useful in the promotion of WIC participation and benefit redemption. This knowledge also would be useful for RDs to use in WIC policy and advocacy.

These issues are challenging for WIC nutritionists, so RDs with expertise in cultural competence and language skills will be valuable for working with today’s increasingly diverse WIC participant population. The biggest challenge for Nevine Abou Dishisha, a WIC nutritionist at Public Health Solutions in New York, is delivering nutrition education to a multicultural population. She says, “Clients are strongly influenced by their families, culture, and religions,” and therefore a nutritionist’s recommendations don’t always align with participants’ practices and values. However, “as a WIC nutritionist, I get to become a part of the family and earn their trust, which is the first step in changing their behavior toward a more healthful diet,” she says, adding that she’d like to have more liberty as a nutritionist to tailor food packages for the needs of individual clients, since needs and preferences vary widely.

Victoria Taylor, CLC, a traveling WIC nutritionist at District 4 Public Health in LaGrange, Georgia, sees the role of the WIC nutritionist as key to helping participants make healthful food choices and commit to regular physical activity. “Many clients don’t know how to read food labels or shop for healthful foods,” Taylor says. “They also can’t afford to go to gyms or RDs.” Taylor is working toward her personal training certificate with the goal of providing exercise classes to WIC participants free of charge. In addition, she believes that knowing how to help clients cook the foods that WIC provides is important. “With the WIC program we teach participants how to make the best out of the foods we offer them.” Her WIC site partners with Cooking Matters to offer weekly hands-on cooking classes. In addition to working with food packages, Taylor holds a CLC (Certified Lactation Consultant) certificate and spends two to three days per week providing participants breast-feeding counseling.

Taylor believes that nutritionists with knowledge of children with special needs, such as sensory issues, have an important role to play in WIC. She says these children often have specific nutrition concerns that require a combination of child development and nutrition knowledge.

Because WIC purchases have a considerable impact on retailers, there are opportunities for RDs to help WIC participants make economical, healthful choices and select, prepare, and store their food.5 Some state agencies administer additional vouchers to participants to purchase foods from farmers’ markets. Currently, more than 3,000 farmers’ markets across the nation accept WIC vouchers under the Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program (FMNP). RDs can work with Cooperative Extension Programs, local chefs, farmers, or farmers’ market associations to provide nutrition education to WIC FMNP recipients. These educational partnerships help FMNP recipients expand their diets by adding fresh fruits and vegetables to their daily meals.

— Christen C. Cooper, EdD, MS, RDN, is founding director of nutrition programs at Pace University in Pleasantville, New York.

References

1. Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Food and Nutrition Service website. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/women-infants-and-children-wic. Updated December 14, 2016.

2. Oliveira V, Frazão E. The WIC program: background, trends and economic issues, 2015 edition. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Report Number 134. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/federal-advocacy/Documents/USDAWIC2015Report.pdf. Published January 2015.

3. Title 7, Code of Federal Regulations, Pt. 246.2. US Government Publishing Office website. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2011-title7-vol4/pdf/CFR-2011-title7-vol4-sec246-2.pdf

4. Rasmussen KM, Latulippe ME, Yaktine AL, eds. Review of WIC Food Packages, Proposed Framework for Revisions: Interim Report. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2016.

5. Carlson S, Neuberger Z. WIC works: addressing the nutrition and health needs of low-income families for 40 years. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities website. http://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/wic-works-addressing-the-nutrition-and-health-needs-of-low-income-families. Published May 4, 2015.