Today’s Dietitian

Vol. 18 No. 3 P. 28

Staying hydrated and fueling up with the right balance of carbs, protein, and fat is key to optimal performance.

Nutrition choices can make or break an endurance runner’s health and performance. Yet there’s no one-size-fits-all eating pattern when it comes to identifying the ideal diet. Much like a fingerprint, each athlete is unique and has varying nutrient needs. And RDs are poised to help clients create a personalized nutrition plan that maximizes their fitness, health, and performance goals.

There are varying definitions of endurance exercise and endurance running. A 2003 document by Saris and colleagues defines endurance as resistance to fatigue and endurance exercise as that lasting 30 minutes or longer.1 From a practical standpoint, Jim White, RD, spokesperson for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and owner of Jim White Fitness & Nutrition Studios in Norfolk, Virginia, defines endurance running as running continuously for at least five miles.

Today’s Dietitian lays the foundation for RDs to help endurance runners achieve optimal nutrition and asks top sports dietitians in the field about common nutrition issues these clients face and how to address them.

Fuel First

Runners who eat healthfully and consume enough calories to support their daily activities and the energy they need for training should remain healthy throughout their lives and be able to enjoy many decades of running, says Lisa Dorfman, MS, RD, CSSD, LMHC, FAND, aka The Running Nutritionist, and author of Legally Lean: Sports Nutrition Strategies for Optimal Health & Performance.

Undoubtedly, endurance runners aspire to perform at their best. However, optimum performance depends on many factors and certainly can’t be achieved without adequate calories to fuel endurance activity and recovery needs. While this concept is perhaps elementary to RDs as nutrition experts, it shouldn’t be assumed it’s readily accepted or well understood by endurance runners. Indeed, sports nutritionist Nancy Clark, MS, RD, CSSD, author of Food Guide for Marathoners: Tips for Everyday Champions and Food Guide for New Runners: Getting It Right from the Start, says calorie restriction is a common challenge because “many runners are very weight conscious and think of food as fattening and not as fuel. So they aren’t fueling properly.” Clark works with her weight-conscious runners to view food as fuel and “get them to think about fueling up, fueling during, and refueling.”

Calculating Calories

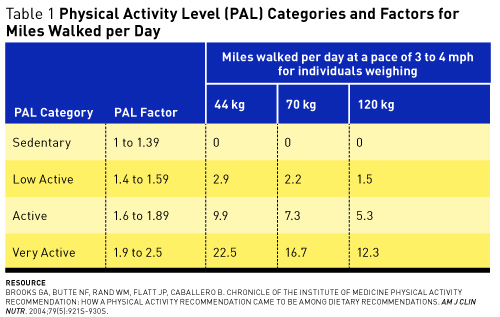

For starters, a runner’s daily calorie needs depend on many factors, including age, gender, weight, activity level, and exercise duration and frequency. To estimate basal metabolic rate (BMR), sports dietitians often employ the Harris-Benedict Equation, which doesn’t require expensive equipment or lab instruments.2 Once BMR is approximated, estimate activity level (sedentary, low active, active, or very active) and corresponding activity factor to calculate calorie needs for the long-distance runner.2 (See Table 1 for activity level categories and factors.)

When Calories Are Inadequate

Insufficient intake of calories in the short term can lead to compromised performance and fatigue onset. Calorie intake that’s inadequate to sustain endurance activity, over time, increases risks of menstrual dysfunction and amenorrhea, bone loss, muscle loss, injury, decreased endurance and strength, compromised immunity and illness, micronutrient deficiencies, and decreased BMR.2-4

Dorfman always watches for signs that a female runner may not be eating enough calories. “If you’re only eating 1,500 calories a day and you really need to eat 1,800 to 2,000, and you’re getting sick, and you’re not menstruating, those are three indications to me that something is amiss and we need to fix it,” she says. RDs can work with clients to develop a thorough list of healthful food choices in appropriate portions, or menu plans, to boost calorie intake if needed.

Carb Phobia

In addition to calorie restriction, weight conscious runners also may shun carbohydrates, White says. “One of the biggest problems runners face is not eating enough carbohydrates to fuel performance. Many runners are afraid to eat carbohydrates because they have a fear of gaining weight and slowing down. This can be the farthest from the truth, as carbohydrates can help fuel the body and improve the speed and performance of runners.”

In fact, as the primary fuel source needed for endurance exercise (fat being the secondary source), sufficient intake of dietary carbohydrates is critically important for the endurance runner to maintain adequate blood glucose levels, maximize muscle and liver glycogen stores, and replenish glycogen stores after exercise.

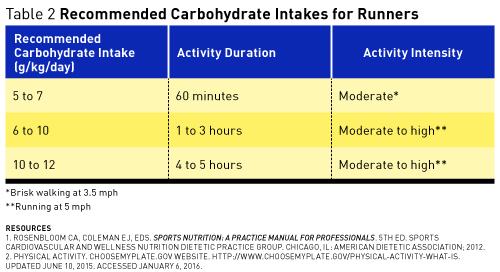

Carb Rx

While in training, individual carbohydrate needs will vary depending on intensity and duration of daily exercise. As a starting point, RDs can apply the guidelines in Table 2 to calculate daily carbohydrate needs for endurance athletes in training.

Protein Needs

Unlike carbohydrates, protein isn’t a significant fuel contributor during activity, but muscle breakdown does occur on long runs. Therefore, endurance runners do have an increased need for dietary protein above and beyond the Dietary Reference Intakes (0.8 g/kg body weight). The current guideline from the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) is a range of 1.2 to 1.4 g/kg body weight.2 If runners are consuming enough calories to maintain weight, they’re likely consuming adequate protein and shouldn’t need protein supplementation. In addition, protein turnover in trained athletes may become more efficient.

Fat Needs

Fat intake also is necessary to sustain prolonged exercise. The recommendation for fat intake in athletes is 20% to 35% of total calories per day,2 matching the needs of nonathletes. High-fat diets (≥70% of total calories per day) or low-fat diets (<20% of total calories per day) aren’t recommended.2

Nutrition Needs for Endurance Events Lasting More Than One Hour

Prerun Objectives: Fueling and Hydrating

The nutrition objectives for endurance runners should be to ensure optimal hydration status and maximize muscle glycogen to help them fuel the run.

To adequately hydrate for a race and decrease the need to urinate during the event, ACSM recommends consuming about 5 mL to 7 mL/kg of body weight of water or sports drink no less than four hours before the race.2 Runners should weigh themselves right before the race to calculate rehydration needs after the run.

A larger, high-carbohydrate meal, between 200 g and 300 g, low in fat and fiber, can enhance performance when eaten three to four hours before the event.2 A smaller meal or snack, such as flavored yogurt with a banana, one hour before the run will allow for gastric emptying to avoid feelings of fullness.

During-the-Run Objectives: Carb Fueling

To optimize performance and prevent fatigue during the run, intake of carbohydrate to maintain blood glucose levels and replacing lost fluids are the primary nutrition objectives.

Ingesting small amounts of carbohydrate during high-intensity runs lasting less than one hour have been shown to improve performance, although glycogen stores likely haven’t been depleted. An optimal quantity of carbohydrate intake hasn’t been reported.2,5-7

Glycogen stores can be exhausted after one to two hours of intense activity. To keep a steady supply of glucose in the blood, the ACSM guidelines call for endurance athletes to consume approximately 30 g to 60 g of carbohydrate per hour of exercise.2 Intestinal absorption capacity and glucose utilization rates are believed to limit higher intakes of carbohydrate per hour, which could potentially cause intestinal distress. However, well-trained endurance athletes can consume and utilize 90 g of carbohydrate per hour during events longer than 21/2 hours from a carbohydrate beverage, gel, or low-fiber, low-fat, low-protein bar.6-8

Depending on weather conditions, runners should drink one-half to two cups of fluid every 15 minutes. Sports drinks with a 6% to 8% carbohydrate concentration (about 50 kcal per cup) enhance fluid intake and provide needed carbohydrate.2,9

Postrun Objectives: Refueling and Rehydrating

Carbohydrate and protein intake are important after the run to refuel and repair muscles, Clark says. In fact, “The muscles are most receptive to refueling after they exercise,” she says, adding that runners should consume three times more carbohydrate than protein, as is found in chocolate milk, which is an excellent recovery food.

To adequately and efficiently replenish muscle glycogen, endurance runners should aim to consume the following:

• 1 to 1.5 g/kg of body weight of carbohydrate within 30 minutes of completing the run; and

• 1 to 1.5 g/kg of body weight of carbohydrate every two hours for four to six hours after the run.2

The immediate postexercise meal also should include some protein (about 15 to 25 g) to minimize continued muscle protein breakdown, spare amino acids from being used for fuel, and stimulate muscle protein synthesis.

If the runner doesn’t consume carbohydrate according to the guidelines above, Clark says, “the recovery window (of time) doesn’t close. They’ll just refuel at a slower rate. It’s possible to refuel up to 24 hours, but if you’re training hard repeatedly every day, then over the course of time you will just get exhausted and your muscles will be depleted because you aren’t doing a good job of refueling.”

Practicing Refueling

Because staying hydrated and maintaining blood glucose levels are imperative during a long-distance run, it’s important for clients to get accustomed to snacking and drinking water or sports drinks during training, White says.

“[Train] your body so come the day of the event you know what foods to eat before and during the event,” Clark adds, noting that athletes shouldn’t eat or drink anything new on race day. They should practice fueling during training so they can be confident on the day of the event, knowing exactly how to maintain blood sugar and prevent dehydration to optimize performance.

Two Nutrients of Concern

Dietitians must also be aware that many endurance runners are at risk of iron and sodium deficiencies since many don’t eat red meat (a source of iron) and don’t replenish enough lost sodium through sweat.

Iron

The lack of iron in the diet of endurance runners often leads to anemia. “Anemia is a big problem among runners,” Clark says. So if a client complains of poor performance, dietitians should consider assessing their diet to determine adequate iron intake. “I had a client whose performance was going downhill,” Clark says. “She figured, ‘Oh, I must be heavy,’ and should go on a diet to lose weight. So she started trying to lose weight that she didn’t have to lose. And the problem was she was running slowly not because she was heavy but because she was anemic.” If runners aren’t red meat eaters, Clark suggests they eat chicken and dark meat fish, such as salmon, snapper, and perch, and cook in a cast iron skillet. Plant foods that are good sources of iron include spinach, Swiss chard, black beans, navy beans, iron-fortified cereals, broccoli, and potatoes. If a client is iron deficient, supplementing with iron may be necessary, Clark says.

Sodium

Sodium is the primary electrolyte that’s lost in sweat during endurance exercise, so the nutrition goal is to prevent hyponatremia, a condition that occurs when sodium levels in the blood are abnormally low. It can result from not replacing substantial sodium lost in sweat during or after a run, or overhydrating before, during, or after exercise. Overhydrating causes the sodium in the body to become diluted. So the longer a person runs and sweats, the higher the risk of developing hyponatremia. Slower runners and new runners are at a greater risk of hyponatremia.

Clark says if a client is running for more than four hours, sodium intake needs to be part of the conversation. Hyponatremia may become a risk when endurance runners overhydrate with either water or sports drinks because the amount of sodium in a sports drink isn’t enough to replace what’s lost. “We have to look at what they’re [eating and drinking] during the race,” Clark says. “For the most part, the longer marathoners should be eating more food, and if they’re choosing wisely they can get sodium in their food. The shorter marathoners don’t need to worry about it because they won’t have the time to overhydrate.”

The amount of sodium lost in sweat depends on many factors, but averages 1 g per liter of sweat.2,10 Sweat rates vary widely from a low output of 0.3 L per hour to upwards of 2.4 L per hour.2,10 For heavy sweaters and those who have a high sodium output in their sweat, Clark suggests they consume 500 mg of sodium per hour. “A lot of people take little packets of salt in a plastic bag and put it in their pocket,” Clark says. “They can just rip it open and lick it if they want to go that route.”

Other micronutrients of concern in athletes are calcium, zinc, magnesium, vitamin D, B vitamins, and the antioxidants vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, and selenium.2 So RDs should evaluate the diets of endurance runners for these micronutrients as well to identify whether dietary adjustments are needed.

The RD’s Role

Dietitians have many roles and responsibilities when working with endurance runners and other athletes. Primarily, RDs educate and guide while working in tandem with clients to develop personalized nutrition and hydration strategies. Ultimately, dietitians will impart to clients what’s perhaps most important, according to Dorfman. And that’s, “Enjoy the run!”

— Andrea N. Giancoli, MPH, RD, is a nutrition communications consultant in Hermosa Beach, California.

[Sidebar 1]

WHY WHEY IS BEST

Whey protein, derived from milk, has a reputation for stimulating muscle synthesis and repair. But is it any more effective than other common proteins found in many products marketed to athletes?

According to Lisa Dorfman, MS, RD, CSSD, LMHC, FAND, aka The Running Nutritionist, and author of Legally Lean: Sports Nutrition Strategies for Optimal Health & Performance, whey protein “is a fast protein in terms of getting into the muscle quickly and the best one to have right after exercise. The other proteins like soy and casein are slower proteins.” However, that doesn’t mean soy and casein proteins aren’t beneficial. Research has shown that endurance athletes need a blend of proteins over the course of the day—some that quickly enter the muscles and some that slowly enter the muscles, so that the proteins can help with muscle repair at varying times throughout the day, Dorfman says.

Whey protein also is higher in leucine, a branched-chain amino acid, than soy and casein. Research suggests that leucine is the amino acid responsible for stimulating muscle synthesis,1 but more evidence is needed.

— ANG

Reference

1. Luiking YC, Deutz NE, Memelink RG, Verlaan S, Wolfe RR. Postprandial muscle protein synthesis is higher after a high whey protein, leucine-enriched supplement than after a dairy-like product in healthy older people: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr J. 2014;13:9.

[Sidebar 2]

BENEFITS OF ENDURANCE TRAINING

• Muscles adapt to store more glycogen and conserve energy

• Trained muscles burn more fat (untrained muscles waste glycogen)

• Increased muscle mass

• Decreased fat mass

• Increased flexibility, muscle strength, muscle endurance, and cardiorespiratory endurance

• Decreased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers

• Increased cardiac output and efficiency of blood delivery

• Decreased resting heart rate

• Reduced blood pressure

• Improved blood circulation

• Increased stroke volume (heart strength)

• Increased HDL

• Increased breathing efficiency

• General sense of well-being and vigor

References

1. Saris WH, Antoine JM, Brouns F, et al. PASSCLAIM — physical performance and fitness. Eur J Nutr. 2003;42(Suppl 1):I50-I95.

2. American Dietetic Association, Dietitians of Canada, American College of Sports Medicine, Rodriguez NR, Di Marco NM, Langley S. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Nutrition and athletic performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):709-731.

3. Brooks GA, Butte NF, Rand WM, Flatt JP, Caballero B. Chronicle of the Institute of Medicine physical activity recommendation: how a physical activity recommendation came to be among dietary recommendations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(5):921S-930S.

4. Rosenbloom CA, Coleman EJ, eds. Sports Nutrition: A Practice Manual for Professionals. 5th ed. Sports Cardiovascular and Wellness Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group. Chicago, IL: American Dietetic Association; 2012.

5. Physical activity. ChooseMyPlate.gov website. http://www.choosemyplate.gov/physical-activity-what-is. Updated June 10, 2015. Accessed January 6, 2016.

6. Jeukendrup AE. Nutrition for endurance sports: marathon, triathlon, and road cycling. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(Suppl 1):S91-S99.

7. Jeukendrup A. The new carbohydrate intake recommendations. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2013;75:63-71.

8. Cermak NM, van Loon LJ. The use of carbohydrates during exercise as an ergogenic aid. Sports Med. 2013;43(11):1139-1155.

9. Sizer FS, Whitney E. Nutrition: Concepts and Controversies. 11th ed. Thomson Wadsworth; Belmont, CA: 2008.

10. Applications of dietary reference intakes for electrolytes and water. In: Panel on Dietary Reference Intakes for Electrolytes and Water, Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intake, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. The National Academies Press: Washington, DC; 2005:449-464.